The Iditarod in Photos: Racing Alaska's Wilderness

The Last Great Race

Dog teams strain at harnesses in anticipation. Yips and barks mingle with a crowd of human voices hemming in contestants that line the race way expectantly. Breath steams like smoke in the cold and a feeling of electricity pulses through the air.

It is the first Saturday of March in Willow, Alaska, the ceremonial starting place and date of the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race. Nicknamed the "Last Great Race," the Iditarod pits man and dog against the harsh but beautiful winter landscape of the Alaskan wilderness.

Begun officially in 1973 as a way to preserve the state's vanishing sled-dog heritage, the Iditarod has reinvigorated the sport and grown into a widely followed event far beyond the bounds of Alaska. The race features some of the world's most elite human and canine athletes competing in one of the world's last great wild places.

The journey of more than a thousand miles

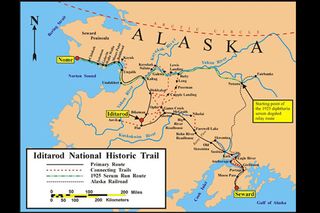

From its starting point near the population center of Anchorage, the Iditarod plunges into the sparsely inhabited interior, traversing rugged mountains, frozen rivers and open tundra in a race towards the finish line at Nome, some 1,150 miles (1,850 kilometers) away on the icy edge of the Bering Sea.

The race follows a northern route in even-numbered years and a southern route in odd-numbered years. Both routes follow the trail for 444 miles (714 km) before diverging and meeting up again 441 miles (709 km) from the finish line in Nome.

The Skwenta River is a popular convergence point for spectators and journalists 40 miles (64 km) from Anchorage and marks a boundary beyond which the trail begins to get more rugged. Skirting the rugged Alaska Range, it is here some racers face their first major obstacle. Balanced on the side of a dangerous incline through a narrow gorge, the section up Rainy Pass is one of the Iditarod's most dangerous checkpoints.

Preserving far north traditions

Woven together by old game trails, Athabascan villages, forgotten Russian fur posts and bygone gold-rush era camps, the Iditarod trail itself is a tapestry of Alaskan memory and heritage. With terrain so rugged no way existed to transport people and goods into the interior during winter, dog sledding became the main form of transportation connecting people and goods.

In the late 1800s, at the height of the infamous Alaska gold rushes, thousands of miners arrived in Nome via steamship during the summer months. From October through June, the northern ports became icebound and dog sleds were the sole means of connecting to the interior gold mining camps.

But by the 1920s, bush planes started to take over the role of mail carriers and suppliers in interior Alaska. Many of the sled dog routes and roadhouses that crisscrossed the wilderness began to dry up and vanish. Still, dog sledding continued to thrive in much of rural Alaska until the 1960s, the year snowmobiles were first introduced.

Snowmobiles vs. snowdogs

As snowmobiles spread throughout Alaska's interior, sled dog teams and sled dog wisdom were being lost. And as the sled dog era began to vanish, some people felt that something of Alaska's spirit was being lost as well.

Coinciding with the 100th anniversary of Alaska becoming a U.S. territory, famous mushers like Joe Redington and impassioned citizens like Dorothy Page teamed up to preserve far north traditions before they disappeared. Their dream was to bring back sled-dog culture while preserving the historic heritage of the old time Iditarod trail run.

Thus, in 1967, a 56-mile (90 km) Centennial race was held. Interest floundered in the early years; however, the vision of the first founders never did. By 1973 a group of fellow mushers helped make the dream a reality with the aid of an army of volunteers, and even the U.S. Army, who helped clear portions of the trail. The tradition of Iditarod had begun.

Into the wild

Once racers have passed over the Alaska Range, they are firmly in the wild interior and enter one of the worst stretches of the trail. Descending from Rainy Pass, mushers and dogs alike brace themselves for a hair raising 1,000-foot (300 meters) elevation drop made over less than 5 miles (8 km). Making it down is just the first of many obstacles, though, as racers enter into the long middle haul.

Already hundreds of miles in by the time teams reach the tiny settlement of Ophir, the trail forks into the northern and southern routes. Alternating the route each year benefits isolated interior villages that anticipate the team arrivals and the attention the race brings to their remote communities.

The determination to push on is strong, but can sometimes be deadly, so sled teams take three mandatory rests, including one 24-hour layover. Teams must also sign in at 27 checkpoints to resupply along the trail. While some racers rest at checkpoints, others push on doggedly, no pun intended!

Winds of the Arctic

The winds of the Arctic scour the Alaskan wilderness in winter, shrieking like a banshee around the poles. Ferocious blizzards and sub-zero temperatures can drop temperatures below minus 50 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 46 degrees Celsius), while wind chill temperatures on the Iditarod trail have been recorded as low as minus 130 F (minus 90 C). In these conditions there is no room for mistakes.

Blizzards can also obscure the trail and hamper teams in thick snow. Getting lost off course is a very real threat. Spread out over thousands of miles of wilderness, even the most experienced teams can, and have, become seriously lost and almost died in past races. Add in fatigue, frostbite even charging moose and it makes you wonder how they do it.

Competing in the Iditarod is the pinnacle of dog sledding and those men and woman who do compete are tough athletes who train year-round. Perhaps even more astounding, though, is the endurance of their dogs. The preferred breeds are Alaskan Malamutes or Siberian Huskies, though more recently the dog of choice has become Alaskan huskies. Like a large malamute and not a true breed, these dogs are born and bred for the rigors of Alaska.

The lure of Alaska

Spanning hundreds of miles of mountains, across tundra and spruce forests, along the boundaries of the great Yukon River, and ending on the frozen wastes of the Bering Sea, the Iditarod is not called the "last great race" for nothing. Alaska is one of the last truly wild places on our planet.

The pioneer spirit has since conquered much of the lower 48, but in Alaska wild landscapes thrive. A sense of the frontier is still palpable and raw, and many that venture "up north" are lured here by the wild, open spaces and pioneer spirit that rewards self-reliance. All of those that compete in the Iditarod share this love of dog sledding, challenge and the wild spirit of Alaska.

Those that compete come mostly from Alaska but some hail from more than a dozen foreign countries. Many come from lands with polar traditions already in place, but competing in the Iditarod is not about where you come from, it is about where you want to go: the finish line! Just ask Newton Marshall, the first ever Jamaican to successfully compete in the Iditarod in 2010.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Dash to the finish

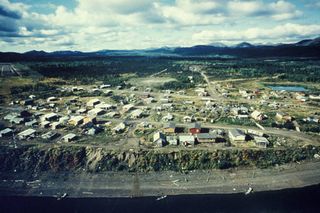

Reaching the Inupiat village of Unalakleet on the shores of the Bering Sea, teams know they have finally entered into the last stretch of the race. Crowds of people cheer, sirens sound and church bells ring to greet them as they make a last dash to the finish line in Nome. By this point some racers report hallucinations from sleep deprivation, but the end is in sight.

After Unalakleet, the last stretch of the Iditarod Trail crosses through Inupiat villages and the frozen expanse of Norton Bay, punctuated by spruce trees in the ice to guide teams to the finish. Following the south shore of the Seward Peninsula along the Bering Sea, the tiny settlement of White Mountain marks the last stop before Nome and the finish line.

Almost all races have been decided by less than an hour in the last stretch, some by less than five minutes. That makes the dash to the finish line crucial. Without a doubt the closest and most memorable finish took place in 1978, when the winner and runner up crossed only one second apart!

What makes a champion?

Since the first race was won in 1973, many things have changed on the Iditarod. Back then it took winner Dick Wilmarth just over 20 days to complete the race. Compare that to the average winning finish of 10 to 8 days now and the race has clearly become far more competitive.

Over time the Iditarod has encouraged the sport of sled dog racing down to a science. Competitors train year-round for the race and must raise considerable funds from sponsors. To the winner go bragging rights to the crown jewel of sled dog racing and a substantial purse. Each year, the best canine athletes are also honored with the "Golden Harness," awarded by vote to the best dogs in the race, frequently those of the winning team, but not always.

Everyone who participates in the Iditarod is a winner, though. Just to compete and cross the finish line is a monumental achievement for all involved, from the first to last competitor. Traditionally, a "widow's lamp" was lit and hung from Nome's roadhouse arch for arriving mushers carrying mail and supplies. The last racer to complete the Iditarod is still honored as the "Red Lantern" in this old tradition.

One of the last wild places

As the most popular sporting event in Alaska, and the premier sled dog race in the world, top mushers and dog teams can turn into celebrities overnight. The popularity of the race has been credited with the resurgence of sled dog racing in Alaska since the 1970s and remains a symbolic link to the history of the state, keeping the tradition of dog mushing alive and well today.

The Iditarod is also a symbolic link to our relationship with the wild. Men and dogs compete against one another, but truly compete with the rugged landscapes of Alaska and the brutal elements of winter. Using their own energy to compete in the traditional way, they honor the land and pay homage to the wild. And so, perhaps the Iditarod is also a call to protect the wild spaces of Alaska and our own wild origins.

I imagine dog teams racing under the green light of the aurora borealis through a wintery world of snow and ice, the enormous space of Alaska smothering them like a blanket and muting all sound. Words fall short though. All I can hear is the panting of dogs racing through the night.

Follow OurAmazingPlanet for the latest in Earth science and exploration news on Twitter @@OAPlanet. We're also on Facebook & Google+.