7 Amazing Grand Canyon Facts

A natural wonder

One of the world's natural wonders, the iconic Grand Canyon draws oohs and aahs from visitors perched at the edge of its towering cliffs. Carved by the copper-colored Colorado River, the colorful rock layers record billions of years of history and hide many unique species. Here are seven amazing facts about the Grand Canyon.

It's not the world's deepest canyon

Though widely considered one of the world's most spectacular canyons, the Grand Canyon is neither the world's longest or deepest gorge.

Its average depth is about 1 mile (1.6 kilometers), though the canyon ranges from 2,400 feet (731 meters) deep below Yavapai Point on the South Rim to 7,800 feet (2,377 m) deep at the North Rim. The canyon wends 277 miles (446 km) along its sinuous path.

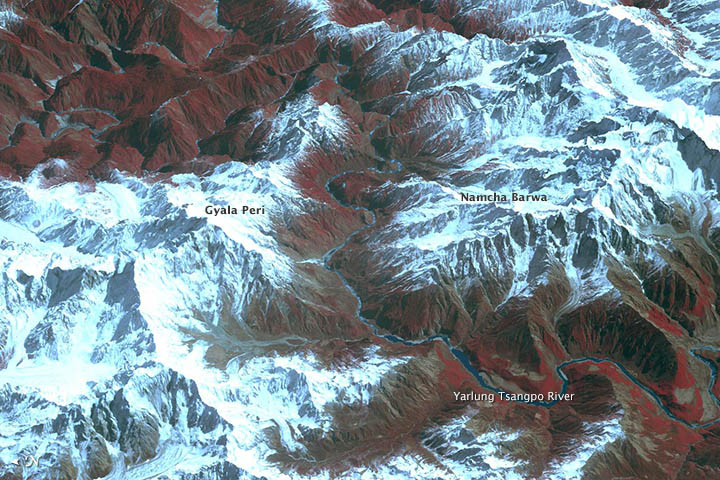

In 1994, the Guinness Book of World Records crowned the Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon in the Himalayas as the world's longest and deepest canyon. Its depth reaches 17,567 feet (5,382 m) and its length 308 miles (496.3 km).

It's also not the world's widest canyon

At its narrowest, at Marble Canyon, the Grand Canyon is only 600 yards (548 meters) across. At its widest, the gorge spans 18 miles (29 kilometers).

On average, the canyon is only 10 miles (16 km) wide from rim to rim, but crossing by foot takes 21 miles (33 km), and driving by car is a 251-mile (403 km), five-hour odyssey. At least the trip is through scenic backcountry.

Australia wins the prize for the world's widest canyon, with its Capertee Valley edging out the Grand Canyon at a little more than 18 miles (30 km) wide.

A canyon plane crash gave rise to the FAA

In the 1950s, passenger flights would sometimes detour over the Grand Canyon for a better view. On June 30, 1956, two planes flying from Los Angeles to Chicago, a United Airlines DC-7 and a TWA Constellation, had both requested permission to fly into the Grand Canyon's airspace. The planes collided directly over the canyon, killing everyone on board. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) was created in 1958 as a result of the crash.

It reveals 40 percent of Earth's history

The Colorado River cuts through schist, a type of metamorphic rock that is 1.75 billion years old. That's nearly half the age of the Earth (which is 4.5 billion years old). Because they are metamorphic rocks, which form from the alteration of other rocks under high temperatures and pressures, these schists represent even more ancient marine and volcanic rocks.

Geologists are drawn to the record of Earth's history contained in sedimentary rocks blanketing the Vishnu schist. These relatively unaltered sediments stopped accumulating about 230 million years ago, and are older than the dinosaurs. Though no dinosaur bones have ever been found in the park, geologically recent fossils, including 11,000-year-old sloth bones, have been found in canyon caves. Many marine fossils and animal tracks also appear in the National Park's rock layers.

Its snakes are pink

Of the six rattlesnake species spotted in the park boundaries, one has an unusual pink hue that matches the local rocks. The Grand Canyon pink rattlesnake is the most common snake in the park, startling hikers as it suns itself on rocks and sandy trails, searching for lizards to eat.

The story of the canyon's names

The Paiute Indian tribe calls the canyon Kaibab, which means "mountain lying down" or "mountain turned upside down." The creamy white Kaibab Limestone forms the surface on which the park's 5 million visitors stand while viewing the canyon.

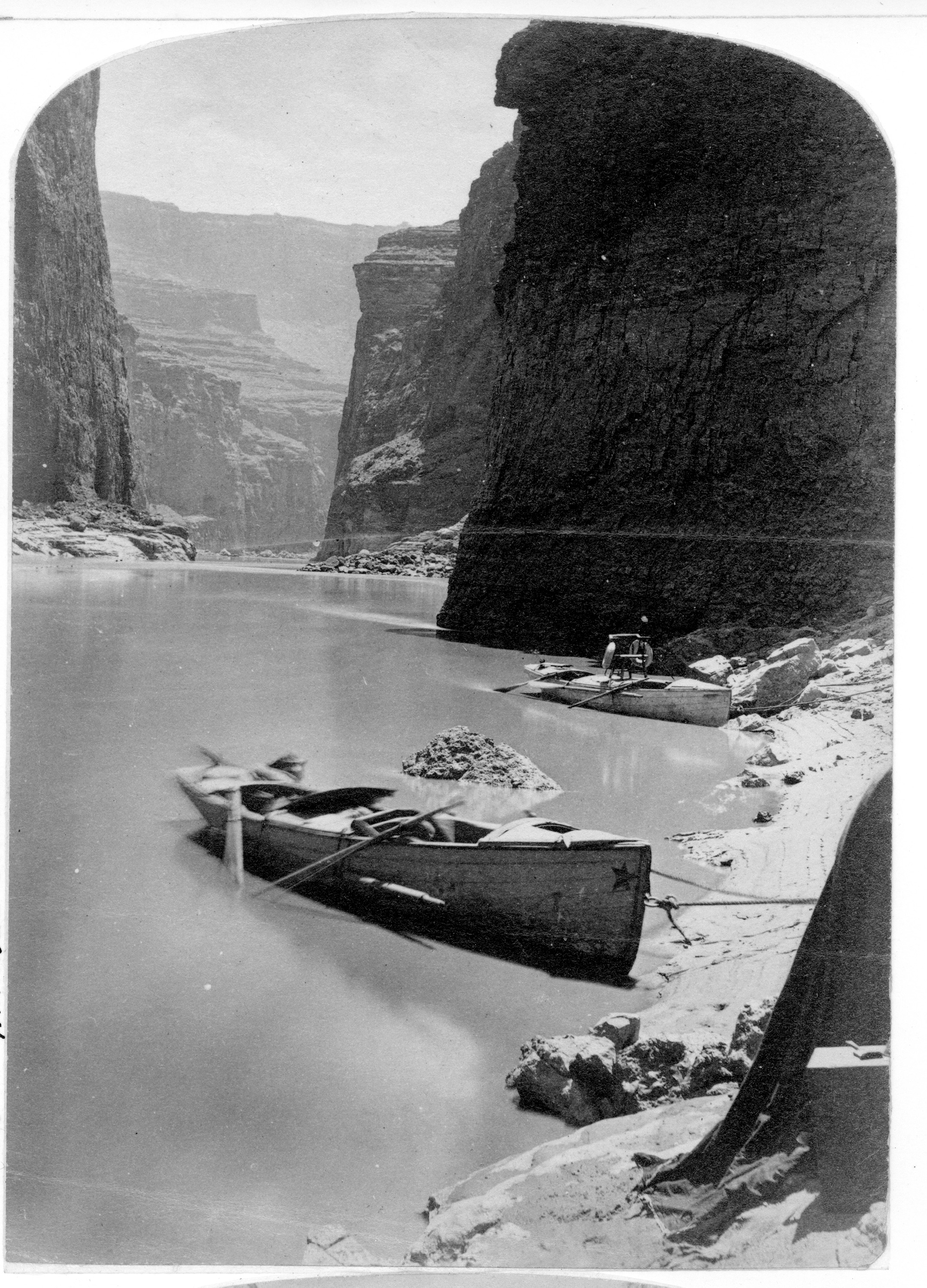

One-armed war veteran John Wesley Powell, who charted the Colorado River's course in 1891 and 1892 in a wooden boat, was the first to consistently use the name "Grand Canyon."

Scientists still don't agree on how it formed

Strong geologic evidence suggests the Colorado River broke out of the west end of the Grand Canyon about five million years ago, and no sooner. But with that constraint, there is heated debate about what the canyon looked like in the millions of years before this anchor.

Did the river carve the canyon all at once? Or was there an ancient gorge waiting for the young river, ready to capture its flow? One recent study found some rocks at the western end were eroded and exposed at the surface 70 million years ago. Active debate continues, with scores of research studies ongoing in the canyon.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.