50 Amazing Tornado Facts

Unknowns

No direct measurements have been made of the winds in the eye of a tornado because the instruments that measure wind can't survive long enough.

High winds

It is thought that winds in the most violent tornadoes can reach speeds as high as 300 mph (480 km/h), according to the NSSL.

Measuring damage

The strength of tornadoes is measured on the Enhanced Fujita scale, which rates tornadoes based on the damage they cause. The ratings on the scale, which run from EF-0 to EF-5, correspond roughly to the strength of the winds seen in the twister. The original Fujita scale was developed by meteorologist Ted Fujita and attempted to relate tornado damage to the wind speeds that caused the damage, as the present EF scale does, but it didn't take into account the fact that winds affect different structures in different ways. The new scale takes these factors into account and rates a tornado based on the most intense damage it caused over its whole path.

Varying degrees

Tornadoes can be on the ground from anywhere between a brief moment to several hours. The NSSL says the average time on the ground is about five minutes.

Fatalities vary

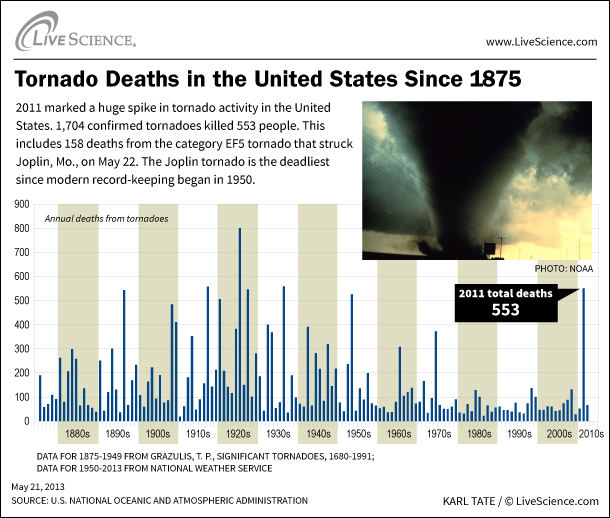

On average, about 60 people are killed by tornadoes each year, but the exact year-to-year numbers vary widely, according to the Storm Prediction Center.

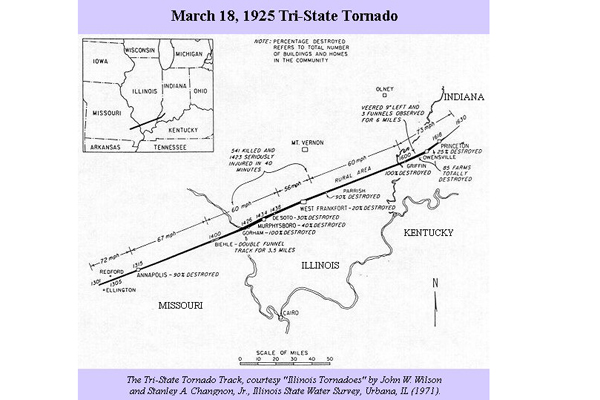

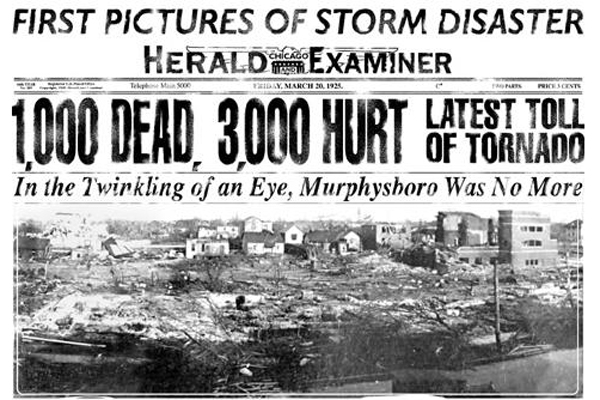

Tri-State Tornado

The deadliest single tornado was the Tri-State Tornado, which hit Missouri, Illinois and Indiana on March 18, 1925, and killed 695 people.

Recent history

The deadliest tornado in the modern era (from 1950 onward) was the EF5 that struck Joplin, Mo., on May 22, 2011, killing 158 people. It ranks as the 7th deadliest tornado in recorded U.S. history.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Expensive weather

The May 22, 2011, Joplin, Mo., tornado was also the costliest on record, causing an estimated $2.8 billion in damage (in 2011 dollars).

Deadly year

1925 is the deadliest tornado year on record in the United States, with 794 people killed by twisters. Nearly 700 were killed on March 18 of that year by the so-called Tri-State Tornado, which virtually wiped several towns off the map.

Deadliest day

The deadliest day for tornadoes was also March 18, 1925, with a reported 747 people killed.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.