Fishing Float Rides 2 Tsunamis ... and Survives

A barrel-size black plastic float torn loose by the 2011 Japan tsunami may have been tossed into a Canadian forest by a second tsunami in 2012, researchers say.

Though the hollow float hasn't been officially confirmed as tsunami debris, it is identical to a float embossed with the name "Musashi" found in the U.S. Dungeness National Wildlife Refuge in May 2012, the researchers said. A similar float was traced to an oyster farm in northeast Japan. The debris from the devastating 2011 tsunami has washed up from Alaska to California to Hawaii.

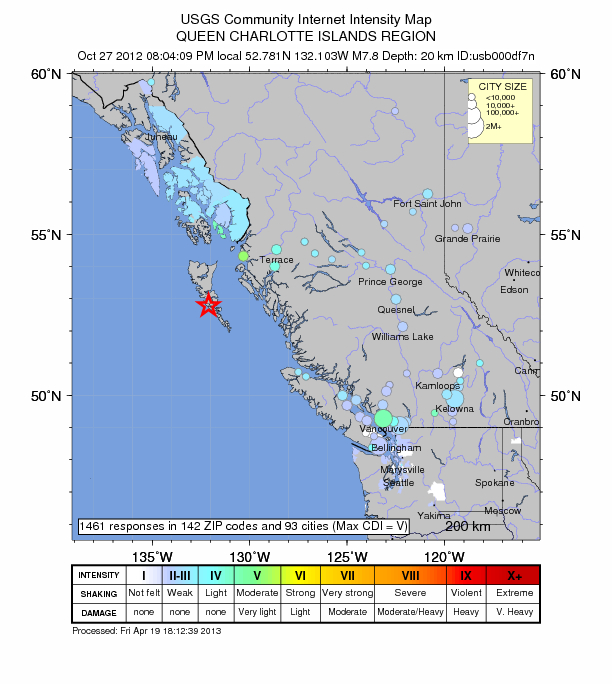

"This is a float that was caught up in the tsunami from Japan, so it is doubly tsunami debris," seismologist Alison Bird of the Geological Survey of Canada said at the Seismological Society of America's annual meeting on April 19. The float was discovered on Moresby Island in British Columbia. The island is part of Haida Gwaii, once called the Queen Charlotte Islands. [Infographic: Tracking Japan's Tsunami Debris]

Second tsunami

The magnitude-7.7 Haida Gwaii earthquake on Oct. 27, 2012, triggered the tsunami, which raced far up western inlets on Moresby Island and Graham Island, but caused little damage on either island's populated eastern side. The powerful wave also sped straight to Hawaii, hitting with a maximum height of 2.5 feet (76 centimeters) and no serious flooding or damage.

The tsunami run-up, which measures how far water surges onshore, was as much as 22 feet (7 meters) in protected bays on the islands' west coasts, Gary Rogers, a Geological Survey of Canada scientist, said at the meeting. (A hurricane-force storm hit the islands just after the earthquake, destroying any record of the tsunami except in protected areas, Rogers said.)

Lucinda Leonard, the Geological Survey scientist who discovered the fishing float, also found dead fish in the forest moss and logs shoved out of place by the tsunami. Seaweed was wrapped around tree branches up to 8 feet (2.5 m) high in Sunday Inlet, near where the float ended its journey.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A strange earthquake

Geologists are still puzzling over the unusual Haida Gwaii earthquake, which surprised scientists because of its unexpected style. Understanding what caused the quake will help them forecast the region's earthquake and tsunami hazards.

Two tectonic plates meet west of Haida Gwaii: the Pacific plate and the North America plate. A strikingly obvious strike-slip fault, the Queen Charlotte fault, has been thought to mark the boundary between the two plates. Strike-slip faults are mostly vertical fractures where two blocks of Earth's crust slide past each other horizontally. The Queen Charlotte unleashed Canada's largest recorded temblors in 1949, a magnitude 8.1.

But the 2012 earthquake was a thrust earthquake, on a previously unknown fault west of the Queen Charlotte fault. The thrust fault hides under a giant pile of sediments. In a thrust quake, two blocks of crust move toward each other, like in subduction zones.

Rethinking the plate boundary

Given the region's ancient tectonic history, there could be a remnant piece of oceanic crust sliding down beneath the southern part of Haida Gwaii, Rogers said. There is some evidence for this from seismic waves, which change their speed when they pass through old, cold crust sitting in hotter mantle rocks. (Earth's mantle lies beneath the crust.)

"It all looks very much like a subduction zone, given the down-bowing of oceanic crust and the accretionary prism [of sediments]," Rogers said. The Pacific plate could be subducting under Haida Gwaii, and thus the North American plate, as far north as the middle of Moresby Island, he said.

Now, scientists want to figure out if the plate boundary is strike-slip or subduction, or a combination of both. They also want to know if there could be bigger earthquakes, and what happens to the Queen Charlotte strike-slip fault when it meets this mysterious new fault. [7 Ways the Earth Changes in the Blink of an Eye]

"If this is some sort of remnant subduction, are we always going to get a small amount of strike-slip with more thrust events?" David Oglesby, a seismologist at the University of California, Riverside, said at the meeting. "It does raise the possibility that you could get significant slip down there."

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.