Archaeologists have unearthed what could be the earliest evidence of ancient human ancestors hunting and scavenging meat.

Animal bones and thousands of stone tools used by ancient hominins suggest that early human ancestors were butchering and scavenging animals at least 2 million years ago. The findings, published April 25 in the journal PLOS ONE, support the idea that ancient meat eating might have fueled big changes in Homo species at that time.

"Just about that time — 2 million years ago — we see big shifts in the human fossil record of increase in brain size, increase in body size and hominins leaving Africa for Eurasia," said study co-author Joseph Ferraro, an archaeologist at Baylor University in Waco, Texas. The meaty meals may have provided the energy for those transformations, he said.

Previously, the earliest evidence of eating meat, found in Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, dates to 1.8 million years ago. But that fossil record doesn't suggest clear evidence of hunting and scavenging for meat until more than a million years later, Ferraro said.

Ancient hunters

Exactly what caused big changes in human ancestors about 1.9 million years ago has been a mystery. Some studies suggest a shift toward a meat-heavy diet enabled the changes, while others suggest that it wasn't only the meat, but cooking meat that made us human.

More than a decade ago, researchers unearthed a trove of thousands of stone tools piled atop animal bones in sandy, silty sediment off the shores of Lake Victoria in Kenya. The artifacts at the site, known as Kanjera, were about 2 million years old and provided some of the earliest evidence of human species living in grassland, rather than forest.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Among the finds were dozens of goat-size gazelles. Most of the bones were found on-site, suggesting their carcasses were brought whole to the site.

In addition, "we find cut marks on their bones where crude stone tools were used to de-flesh the animal and to remove their meat and their organs," Ferraro told LiveScience.

The combination of evidence suggests the animals must have been hunted, not scavenged. (In modern-day Africa, scavengers don't eat such animals because their primary predators, such as lions and hyenas, will consume them entirely, leaving nothing behind.)

The site also contained the cracked skulls of larger antelopes, similar in size to wildebeests.

The researchers concluded that these skulls were likely scavenged by the ancient hominins. Even today, the Serengeti is littered with wildebeest-size heads, Ferraro said.

"Scavengers like hyenas will consume all the rest of the carcass, but they'll leave the heads behind because they can't crack them open to extract the brains," Ferraro said. [Image Gallery: Hyenas at the Kill]

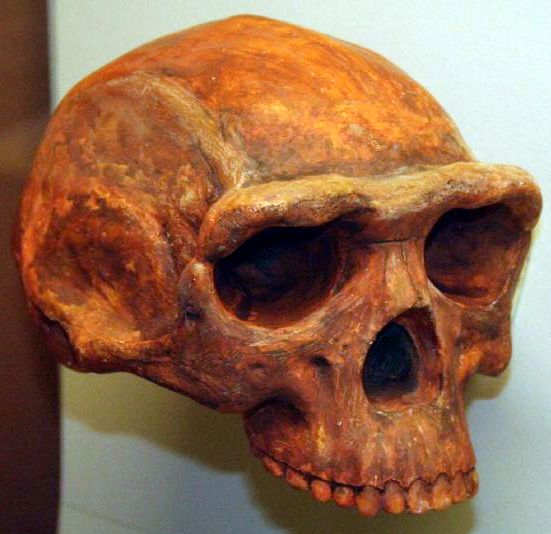

The team hypothesized that ancient human ancestors found the discarded heads in their landscape, and then cracked open the skulls to access the fatty, nutritious, energy-rich brains. That might have fueled the body changes seen later in modern-human ancestors such as Homo erectus.

Mystery man

So far, however, the researchers have found no traces of the hominins who hunted those animals.

Although researchers aren't exactly sure who these human ancestors were, they certainly walked upright and were adapted to living on the grassland — possibly H. erectus or its immediate predecessor, Ferraro said.

Editor's Note: This story has been corrected to note that Olduvai Gorge is in Tanzania, not Kenya.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter @tiaghose. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.