Breast Cancer: How We'll Better Predict Who it Strikes (Op-Ed)

Annette Lee, associate investigator at the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, contributed this article to LiveScience's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

We may never be able to fully prevent the occurrence of breast cancer, but I believe within five years we will be able to identify individuals who will develop breast cancer with much higher accuracy than we can with the predictive tools we have now.

Currently, many women make difficult medical decisions based on age, ethnicity, medical history, family history, lifestyle and BRCA-gene status that are weighted independently and collectively to estimate risk for the development of breast cancer. [Angelina Jolie & Breast Cancer: What Options Do High-Risk Women Have?]

However, a woman with all odds against her may never develop breast cancer, while another with no known risk factors may succumb to the disease within a few years. There are still many unknowns.

Currently, large cohorts of women with a diagnosis of breast cancer are providing information to researchers and the technology to discover previously unknown genetic factors is rapidly developing — both outcomes bring the opportunity for new discoveries.

While there is no doubt BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic mutations significantly increase a woman's risk of developing breast cancer, they are not the only factors involved. Some women who have the known BRCA mutations never go on to develop breast cancer; while some women with no BRCA mutations do. There are several ongoing genetic studies to identify other gene mutations involved in the development of breast cancer.

In addition, the ability to sequence whole genomes has increased exponentially, while the costs have decreased. That has helped change the way we now view DNA and RNA. Segments we once thought of as "junk" or "spacer" DNA have turned out to be key gene regulators.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

More emphasis is also being placed on not just DNA sequencing, per se, but other genetic components, as well. Small, non-coding RNA sections are now recognized as important molecules in modifying gene expression — especially in cancer. The influences of DNA and histone modifications, which also affect gene expression, are also actively being explored.

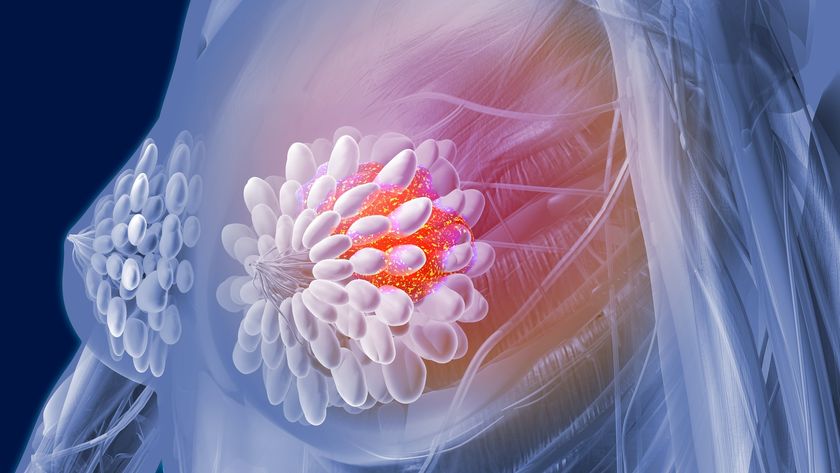

The development of cancer does not happen overnight. There is a progression of steps that need to occur for cancer to be potentially lethal. First, normal cells need to transform into cancer cells, the cancer cells need to divide, expand and not die at the same rate as normal cells — and more importantly, the cancer cells need to spread (metastasize) to other parts of the body and continue their invasion of healthy tissue. If we can interrupt that chain of events at any point, we can save lives.

In collaboration with Iuliana Shapira, M.D., at the Monter Cancer Center, we have been collecting blood and tumor samples from women diagnosed with breast and/or ovarian cancer to study the course of the disease from diagnosis through completion of treatment. By studying samples from the same person at different points, we can identify changes at the DNA-, RNA- and protein-level that reflect the presence of cancer, disease status, treatment response and, in some cases, relapse. Data on multiple factors from serial time points gives us important insight into what makes cancer cells different from normal cells and how we can potentially leverage this information towards prevention, detection and treatment.

We are also collecting longitudinal (yearly) blood samples from women who are at high risk for developing cancer to see if biomarkers are present that could indicate future cancer development. Indentifying measureable, pre-cancer changes would give us a tool to distinguish women who are at high risk for developing cancer, but may not distinguish women who are at high risk who will go on to develop cancer in the near future. The key to curing cancer is early detection.

With the availability of subject samples to study and the methods to perform in-depth genetic analysis on multiple levels, we will ultimately be better equipped to accurately identify and define an individual's risk of developing breast cancer rather than relying on population statistics.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

Original article on LiveScience.com.