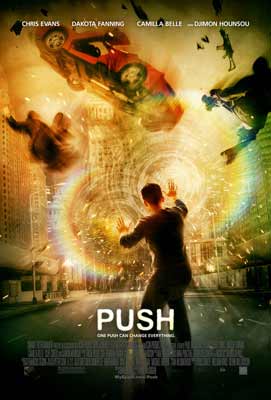

Movie to 'Push' Dubious Psychic Powers

The movie "Push," in theaters Feb. 6, is about a group of young Americans with various psychic abilities who team up to use their paranormal powers against a shadowy U.S. government agency tracking them.

One of the psychic powers featured in the film is psychokinesis, also known as telekinesis or, less formally, "mind over matter."

The idea of people being able to move objects through mind power alone has intrigued people for centuries, though only in the late 1800s did it become popular and seen as an ability that could be demonstrated. This occurred during the heyday of Spiritualism, when psychic mediums claimed to contact the dead during séances, and objects would suddenly and mysteriously move, float, or fly by themselves across the darkened room, untouched by human hands.

Tables would tip (in a process rather unimaginatively called table-tipping) as either spirits or the psychic's mind supposedly caused the disturbances.

In fact, fraudulent psychics resorted to trickery, using everything from hidden wires to covert associates to make objects appear to move untouched. Because the medium's hands were sometimes tied, or joined with others at the table, the table-tipping seemed mysterious but was in fact easily accomplished with dextrous feet and strong toes.

Houdini exposed them

Harry Houdini, best known for his amazing magic and escape acts, tirelessly investigated and exposed fake mediums, and even wrote a book about it, "Miracle Mongers and Their Methods."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As the public grew wise to the fake psychics, the phenomenon diminished — until the 1930s and 1940s, when a researcher at Duke University named J.B. Rhine became interested in the idea that people could affect the outcome of random events using their minds.

Rhine began with tests of dice rolls, asking subjects to try and influence the outcome through concentration. Though his results were mixed and hardly robust, they were enough to convince him that there was something mysterious going on. Unfortunately for Rhine his experiments failed a crucial scientific test, that of replicability: other researchers were unable to duplicate his findings. Errors were found in his methodology, and the topic faded away.

Psychokinesis popped back into the spotlight again three decades later with the emergence in the 1970s of a charismatic Israeli spoon-bender named Uri Geller.

Geller became the world's best-known psychic superstar and made millions traveling the world demonstrating his claimed psychokinetic abilities. Though he denied using magic tricks, many skeptical researchers, including James "The Amazing" Randi, observed that all of Geller's amazing feats could be — and have been — duplicated by magicians. Randi famously quipped, "If Geller is bending spoons with his mind, he's doing it the hard way."

Real evidence finally?

In 1976, several children who claimed to have psychokinetic powers were tested in controlled experiments at the University of Bath. Perhaps taking a cue from Geller, they claimed the ability to bend metal objects such as spoons. For a while the results seemed promising, and experimenters believed they might finally have found real scientific evidence of psychokinesis. Unfortunately, the children were caught cheating on hidden cameras, physically bending spoons with their hands — not their minds — when they thought no one was watching.

Other frauds were also discovered; proof remained elusive, and once again the "mind over matter" phenomenon faded away.

Thirty years later, the cycle continues anew.

In 2007 during an Isreali television show, Uri Geller was caught on camera putting a tiny object, thought to be a magnet, on his thumb just before succeeding in his attempt to move a compass needle using only his mind. He denied using a magician's thumb trick but sued YouTube, demanding the removal of a slow-motion video clip of that show. The clip remains available to the public.

The history of psychokinesis is riddled with fraud, both proven and suspected. But even more devastating is the inability of researchers to replicate any positive findings. The problem is not a lack of studies; researchers have spent decades trying to find good evidence. Many researchers studying psychokinesis admit that the data falls far short of scientific standards of proof, and they face an even bigger problem: there is no known mechanism by which the human mind could remotely influence material objects.

"Push," like many movies, claims to be based on real events. If that’s true, look for the scenes of the young psychics getting caught faking their abilities. Until the long-sought scientific proof of psychic power is found, psychokinesis — like "Push" — is more fiction than fact.

Benjamin Radford is managing editor of the Skeptical Inquirer science magazine. His books, films, and other projects can be found on his website. His Bad Science column appears regularly on LiveScience.