What is Thundersnow?

Thundersnow was heard rumbling in several places along the East Coast last night (Jan. 26), including Washington, Philadelphia and New York.

Thundersnow is a rarity, a wintertime thunderstorm with snow instead of rain. These storms spawn long, low rumbles of thunder, sometimes with lightning flashes. The lightning can stretch out in long creepy-crawly branches moving over tens of miles, similar to the lightning in squall line storms during Midwestern summers.

Thundersnow is caused by an upward rush of air from the ground to high in the atmosphere, paired with temperatures at or below freezing. This cold air keeps the snow from melting into rain. Snow can fall at intense rates during such a storm. In New York City, snowfall was reported at 3 inches (8 centimeters) per hour at times yesterday. [Related: What's a Blizzard? ]

Thundersnow is most commonly created along with lake effect snow. It's still a relatively rare event, yet such rare events can spell big trouble, such as lightning strikes, said Walt Petersen, an atmospheric scientist with NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala.

Petersen should know: Lightning once struck the corner of his house.

"The fact that it happens during a snow event makes it even more intrinsically interesting," Petersen told OurAmazingPlanet.

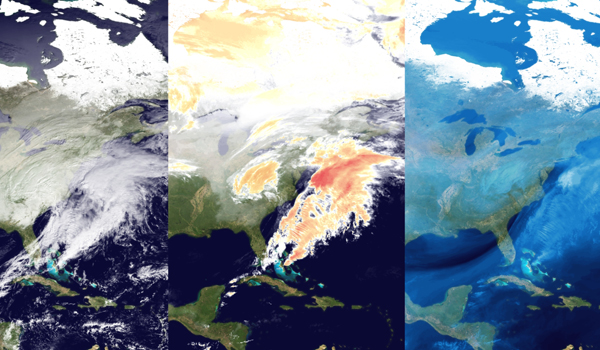

Petersen recently witnessed thundersnow in Huntsville. As the city was blanketed with about 7 inches (18 cm) of snow Jan. 9, Petersen and colleagues aimed their NASA radars and satellites at the snowstorm and collected the most detailed set of data to date on snow in the southern United States.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

It is suspected that thundersnow and thunderstorms are similar in how they make thunder and lightning. One difference is that thundersnow doesn't have as much super-cooled liquid water. Super-cooled water is what creates the electric charge that generates the lightning and thunder. Without as much of it, thundersnow events end up with an electric field that is much larger and takes longer to create.

Petersen's recent Huntsville snow data could help improve thundersnow forecasts, which would be important for public safety and would help power grid operators prepare for storms.

This article was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to Life's Little Mysteries. Reach OurAmazingPlanet staff writer Brett Israel at bisrael@techmedianetwork.com. Follow him on Twitter @btisrael.

Got a question? Send us an email and we'll look for an expert who can crack it.