7 everyday things that happen strangely in space

Microgravity changes a lot of the physical conditions we take for granted on Earth.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Watched pots, as they say, never boil. Besides, even if they did, why watch them? You know exactly what boiling water looks like.

But I bet you don't know what it looks like in outer space.

Here are seven everyday occurrences including the boiling of water that happen very differently in the microgravity environment of low-Earth orbit, plus explanations why.

Water boils in a big bubble

On Earth, boiling water creates thousands of tiny vapor bubbles. In space, though, it produces one giant undulating bubble.

Fluid dynamics are so complex that physicists didn't know for sure what would happen to boiling water in microgravity until the experiment was finally performed in 1992 aboard a space shuttle. Afterward, the physicists decided that the simpler face of boiling in space probably results from the absence of convection and buoyancy two phenomena caused by gravity. On Earth, these effects produce the turmoil we observe in our teapots.

Much can be learned from these boiling experiments. According to NASA Science News, "Learning how liquids boil in space will lead to more efficient cooling systems for spacecraft ... [It] might also be used someday to design power plants for space stations that use sunlight to boil a liquid to create vapor, which would then turn a turbine to produce electricity."

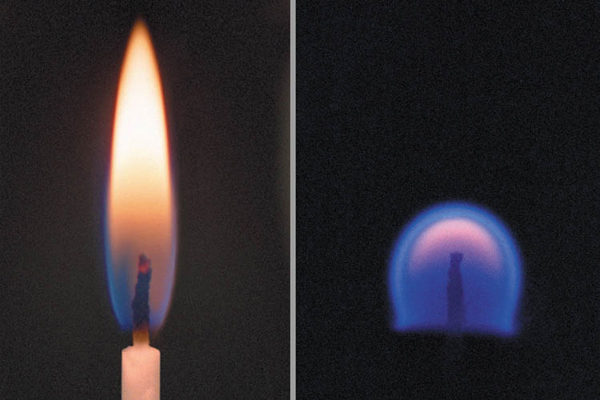

Flames are spheres

On Earth, flames rise. In space, they move outward from their source in all directions. Here's why:

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The closer you are to the Earth's surface, the more air molecules there are, thanks to the planet's gravity pulling them there. Conversely, the atmosphere gets thinner and thinner as you move vertically, causing a gradual decline in pressure. The atmospheric pressure difference over a height of one inch, though slight, is enough to shape a candle flame.

That pressure difference causes an effect called natural convection. As the air around a flame heats up, it expands, becoming less dense than the cold air surrounding it. As the hot air molecules expand outward, cold air molecules push back against them. Because there are more cold air molecules pushing against the hot molecules at the bottom of the flame then there are at its top, the flame experiences less resistance at the top. And so it buoys upward.

When there's no gravity, though, the expanding hot air experiences equal resistance in all directions, and so it moves spherically outward from its source.

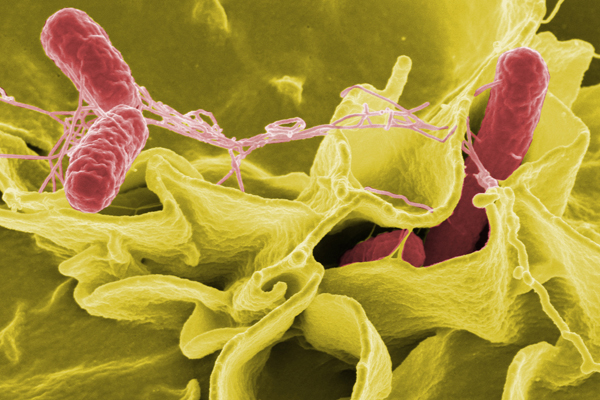

Bacteria grow more... and grow more deadly

Thirty years of experiments have shown that bacterial colonies grow much faster in space. Astro-E. coli colonies, for example, grow almost twice as fast as their Earth-bound counterparts. Furthermore, some bacteria grow deadlier. A controlled experiment in 2007 testing salmonella growth on the space shuttle Atlantis showed that the space environment changed the expression of 167 of the bacteria's genes. Studies performed after the flight found that these genetic tweaks made the salmonella almost three times more likely to cause disease in mice than control bacteria grown on Earth.

There are several hypotheses as to why bacteria thrive in weightlessness. They may simply have more room to grow than they do on Earth, where they tend to clump together at the bottom of petri dishes . As for the changes in gene expression in salmonella, scientists think they may result from a stress response in a protein called Hfq, which plays a role in controlling gene expression. Microgravity imposes mechanical stresses on bacterial cells by changing the way liquids move over their surfaces. Hfq responds by entering a type of "survival mode" in which it makes the cells more virulent.

By learning how salmonella responds to stress in space, scientists hope to learn how it might handle stressful situations on Earth. Hfq may undergo a similar stress response, for example, when salmonella is under attack by a person's immune system.

You can't burp beer

Because no gravity means no buoyant force, there's nothing pushing gas bubbles up and out of carbonated drinks in space. This means carbon dioxide bubbles simply stagnate inside sodas and beers, even when they're inside astronauts' bellies. Indeed, without gravity, astronauts can't burp out the gas and that makes drinking carbonated beverages extremely uncomfortable.

Luckily, a company in Australia has concocted a brew that'll be just the thing for kicking back on spaceflights. Vostok 4 Pines Stout Space Beer is rich in flavor, but weak in carbonation. A nonprofit space research organization called Astronauts4Hire is looking into whether the beer will be safe for consumption on future commercial spaceflights.

A rose by the same name smells... different

Flowers produce different aromatic compounds when grown in space, and as a result, smell notably different. This is because volatile oils produced by plants the oils that carry fragrance are strongly affected by environmental factors like temperature, humidity and a flower's age. Considering their delicacy, it isn't surprising that microgravity would affect the oils' production as well.

An "out of this world" fragrance produced by a variety of rose called Overnight Scentsation flown on the space shuttle Discovery in 1998 was later analyzed, replicated and incorporated into "Zen," a perfume sold by the Japanese company Shiseido.

Space sweat

As explained in the context of candle flames, zero g's means there's no natural convection. This means body heat doesn't rise off skin, so the body constantly perspires in an effort to cool itself down. Even worse, because that steady stream of sweat won't drip or evaporate, it simply builds up. All this makes for a pretty moist journey to the beyond.

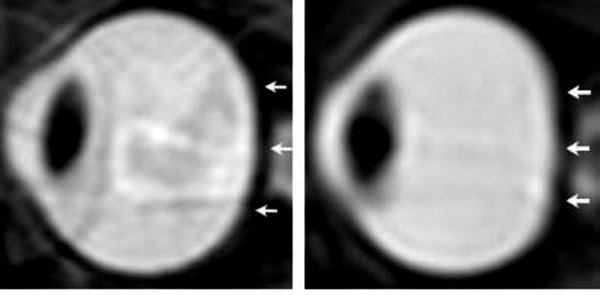

Squashed eyeballs

Weightlessness squashes astronauts' eyeballs, blurring their vision. The backs of some astronauts' eyes get flattened, while others experience swelling of their optic nerves conditions that result on Earth from abnormally high fluid pressure in the head. It happens for similar reasons in the zero-g environment of space. Without the downward pull of gravity, body fluids ride higher than they normally would, and so there's more fluid than usual in the skull pressing on the eyes.

While this effect would blur the vision of most people, the nearsighted among us whose eyes are normally overextended would get a vision boost from the eyeball flattening effect. The optic nerve swelling wouldn't help anyone, however, and could even cause blindness if left untreated. Thus, eyeball problems may be a limiting factor in the duration of future missions to Mars and beyond.

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science from 2010 to 2012 and is currently a senior physics writer and editor for Quanta Magazine. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with the staff of Quanta, Wolchover won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory writing for her work on the building of the James Webb Space Telescope. Her work has also appeared in the The Best American Science and Nature Writing and The Best Writing on Mathematics, Nature, The New Yorker and Popular Science. She was the 2016 winner of the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award, an annual prize for young science journalists, as well as the winner of the 2017 Science Communication Award for the American Institute of Physics.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus