14 of the deadliest natural disasters in history

The world's deadliest natural disasters span more than 2,500 years of human history and include earthquakes, tsunamis and cyclones.

- Aleppo earthquake

- Indian Ocean earthquake

- Tangshan earthquake

- A.D. 115 Antioch earthquake

- A.D. 526 Antioch earthquake

- Calcutta cyclone

- Haiyuan earthquake

- Coringa cyclone

- Haiphong typhoon

- Haiti earthquake

- Bhola cyclone

- Shaanxi earthquake

- Yellow River flood

- Yangtze River floods

- Additional resources

- Bibliography

Every year, some of the deadliest natural disasters — earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, hurricanes, tsunamis, floods, wildfires and droughts — kill nearly 60,000 people, according to Global Change Data Lab.

Violent natural disasters have been a fact of human life since the beginning of humankind, but the death counts of the most ancient of these disasters are lost to history. The ancient Mediterranean island of Thera (now Santorini, Greece), for example, experienced a catastrophic volcanic eruption that eradicated the entire Minoan civilization around 1600 B.C., according to a 2020 study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences. But exactly how many lives were lost? We'll never know.

However, thanks to historical records and journals, historians can at least estimate the number of fatalities linked to disasters that occurred in the common era. According to such records, the following natural disasters are some of the deadliest of all time.

The A.D. 1138 Aleppo earthquake

On Oct. 11, 1138, the ground under the Syrian city of Aleppo began to shake. The city sits on the confluence of the Arabian and African plates, making it prone to temblors, but this one was particularly violent. The magnitude of the quake is lost to time, but contemporary chroniclers reported that the city's citadel collapsed and houses crumbled across Aleppo. The resulting death toll is estimated at around 230,000, but that figure comes from the 15th century, and the historian who reported it may have conflated the Aleppo quake with one that occurred in what is now the modern-day Eurasian country of Georgia, according to a 2004 paper in the journal Annals of Geophysics. Still, this supposed death toll marks this event as one of the most deadly natural disasters of all time.

The 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami

Another deadly natural disaster was a catastrophic magnitude 9.1 earthquake that struck undersea off the west coast of Sumatra, Indonesia, on Dec. 26, 2004. The quake created a massive tsunami that killed approximately 230,000, and displaced nearly 2 million people in 14 South Asian and East African countries. Traveling as fast as 500 mph (804 km/h), the tsunami reached land in as little as 15 to 20 minutes after the quake hit, giving residents little time to flee to higher ground.

In some places, especially hardest-hit Indonesia, the tsunami wave reached over 100 feet (30 meters) high, according to World Vision, a humanitarian aid organization.

Damages from the earthquake and tsunami are estimated at $10 billion dollars. This event is considered the third largest earthquake in the world since 1900, and its tsunami has killed more people than any other tsunami in recorded history, according to NOAA's National Centers for Environmental Information.

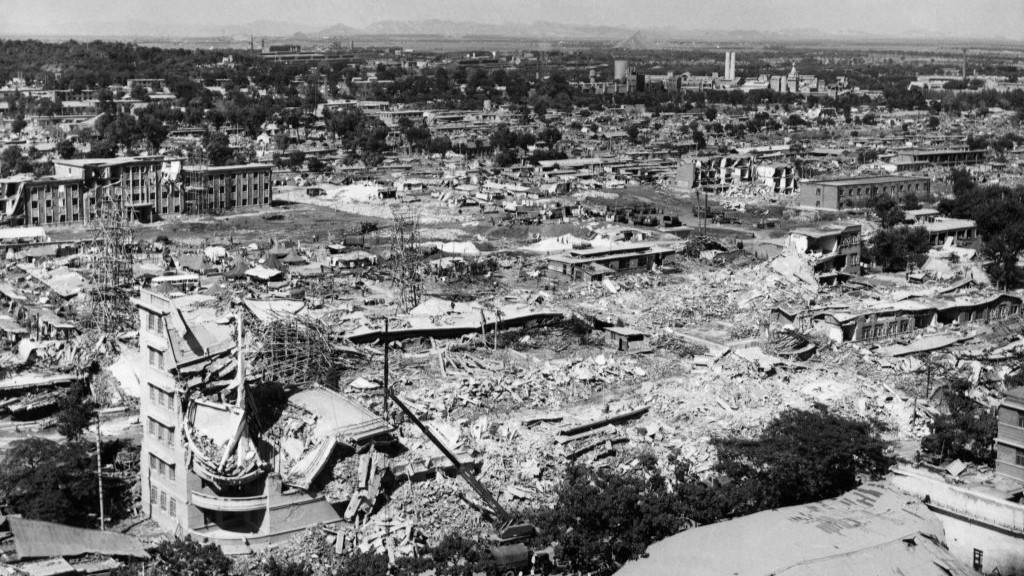

The 1976 Tangshan earthquake

At 3:42 a.m. on July 28, 1976, the Chinese city of Tangshan was razed to the ground by a magnitude 7.8 earthquake, according to a report by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). Tangshan, an industrial city with a population of about 1 million at the time of the disaster, suffered staggering casualties of over 240,000. While this was the official death toll, some experts suggest this number is grossly underestimated and that the loss of life was likely closer to 700,000. Reportedly, 85% of Tangshan's buildings collapsed, and trembles were felt in Beijing, China, more than 100 miles (180 km) away. It took several years before the city of Tangshan was rebuilt to its prior glory.

The A.D. 115 Antioch earthquake

The Hellenistic Greek city of Antioch, which served as a regional capital to both the Roman and Byzantine empires, sits in modern-day Turkey atop a triple tectonic junction between the African plate, the Arabian plate and the Anatolian sub-plate. On Dec. 13, A.D. 115, the tectonic system beneath the city produced an estimated magnitude 7.5 earthquake that reached an "extreme" intensity on the Mercalli intensity scale.

The earthquake resulted in approximately 260,000 deaths and destroyed Antioch, as well as five nearby cities. It also triggered a local tsunami that severely damaged Beirut, the capital of modern-day Lebanon, and the harbor of an ancient port city called Caesarea Maritima. The Roman emperor Trajan was caught in the earthquake while wintering in Antioch and became trapped under the rubble of his home, but he managed to escape with only minor injuries.

The A.D. 526 Antioch earthquake

As with all disasters occurring millenia ago, a precise death toll for the A.D. 526 Antioch earthquake is hard to come by. Contemporary chronicler John Malalas wrote at the time that about 250,000 people died when the temblor hit the Byzantine Empire city (now Turkey and Syria) in May, 526. Malalas attributed the disaster to the wrath of God and reported that fires destroyed everything in Antioch that the earthquake did not.

According to a 2007 paper in The Medieval History Journal, the death toll was higher than it would have been at other times of the year because the city was full of tourists celebrating Ascension Day — the Christian feast that commemorates Jesus' ascension into heaven.

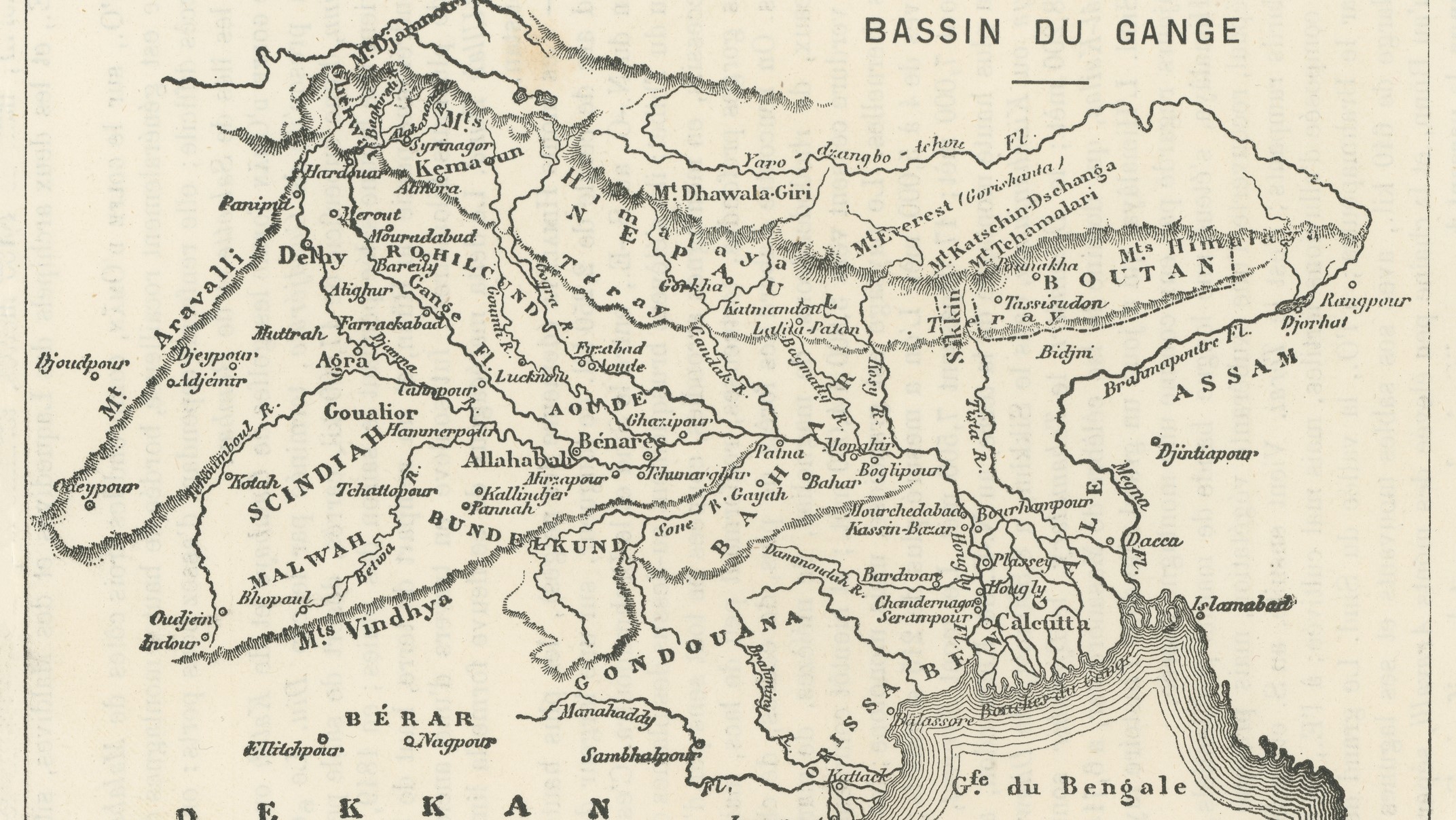

The 1737 Calcutta cyclone

The 1737 Calcutta cyclone, also known as the Hooghly River cyclone, made landfall in the Ganges Delta just south of the city of Calcutta (modern-day Kolkata), in India's West Bengal state, early in the morning of Oct. 11, 1737 — although some accounts say the storm occurred on Sept. 30. The cyclone is the earliest super-cyclone on record in the North Indian Ocean, meaning it had wind speeds of at least 140 mph (225 km/h) that were sustained for 3 minutes.

The cyclone caused a storm surge up to 40 feet (13 meters) high in the Ganges and traced a 200-mile-long (320 kilometers) path of destruction. It left few buildings standing in Calcutta and sank roughly 20,000 boats in the Bay of Bengal. The storm caused 300,000 deaths according to some accounts — but researchers point out there is a discrepancy between this casualty count and the urban population of Calcutta at the time, which was less than 20,000.

The 1920 Haiyuan earthquake

"The Haiyuan earthquake was the largest quake recorded in China in the 20th century with the highest magnitude and intensity," Deng Qidong, a geologist with the Chinese Academy of Sciences, said during a seminar in 2010.

Related: How are earthquakes measured?

The earthquake, which struck north central China's Haiyuan County on Dec. 16, 1920, also rocked the neighboring Gansu and Shaanxi Provinces. It was reportedly a 7.8 on the Richter scale, however, China today claims it was of magnitude 8.5. There are also discrepancies in the number of lives lost. The USGS reported total casualties of 200,000, but according to a 2010 study by Chinese seismologists, the death toll could have been as high as 273,400. The region's high deposits of loess soils (porous, silty sediment that's very unstable) triggered massive landslides which were responsible for over 30,000 of these deaths, according to a 2020 study published in the journal Landslides.

The 1839 Coringa cyclone

The Coringa cyclone made landfall at the port city of Coringa on India's Bay of Bengal on Nov. 25, 1839, whipping up a storm surge of 40 feet (12 m), according to NOAA's Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory Hurricane Research Division. The hurricane's wind speeds and category are not known, as is the case for many storms that took place before the 20th century. About 20,000 ships and vessels were destroyed, along with the lives of an estimated 300,000 people.

The 1881 Haiphong typhoon

Another disaster with a similar death toll as the Coring cyclone is the 1881 typhoon that hit the port city of Haiphong in northeastern Vietnam on Oct. 8. This storm is also believed to have killed an estimated 300,000 people.

The 2010 Haiti earthquake

The catastrophic magnitude 7.0 earthquake that struck Haiti just northwest of Port-au-Prince on Jan. 12, 2010, ranks as one of the three deadliest quakes of all time.

Haiti's standing as one of the poorest countries in the Western Hemisphere and its limited history of large earthquakes left it extremely vulnerable to damages and loss of life. As many as 3 million people were affected by the quake. Death toll estimates were all over the place; initially, the government of Haiti estimated fatalities stood at 230,000 people, but in January 2011, officials revised that figure to 316,000. A 2010 study published in the journal Medicine, Conflict and Survival put the number at around 160,000 deaths, while the USGS claimed even lower numbers — around 100,000. These disparities reflect the difficulty of counting deaths even in the modern era, not to mention the political wrangling that goes on over "official" numbers.

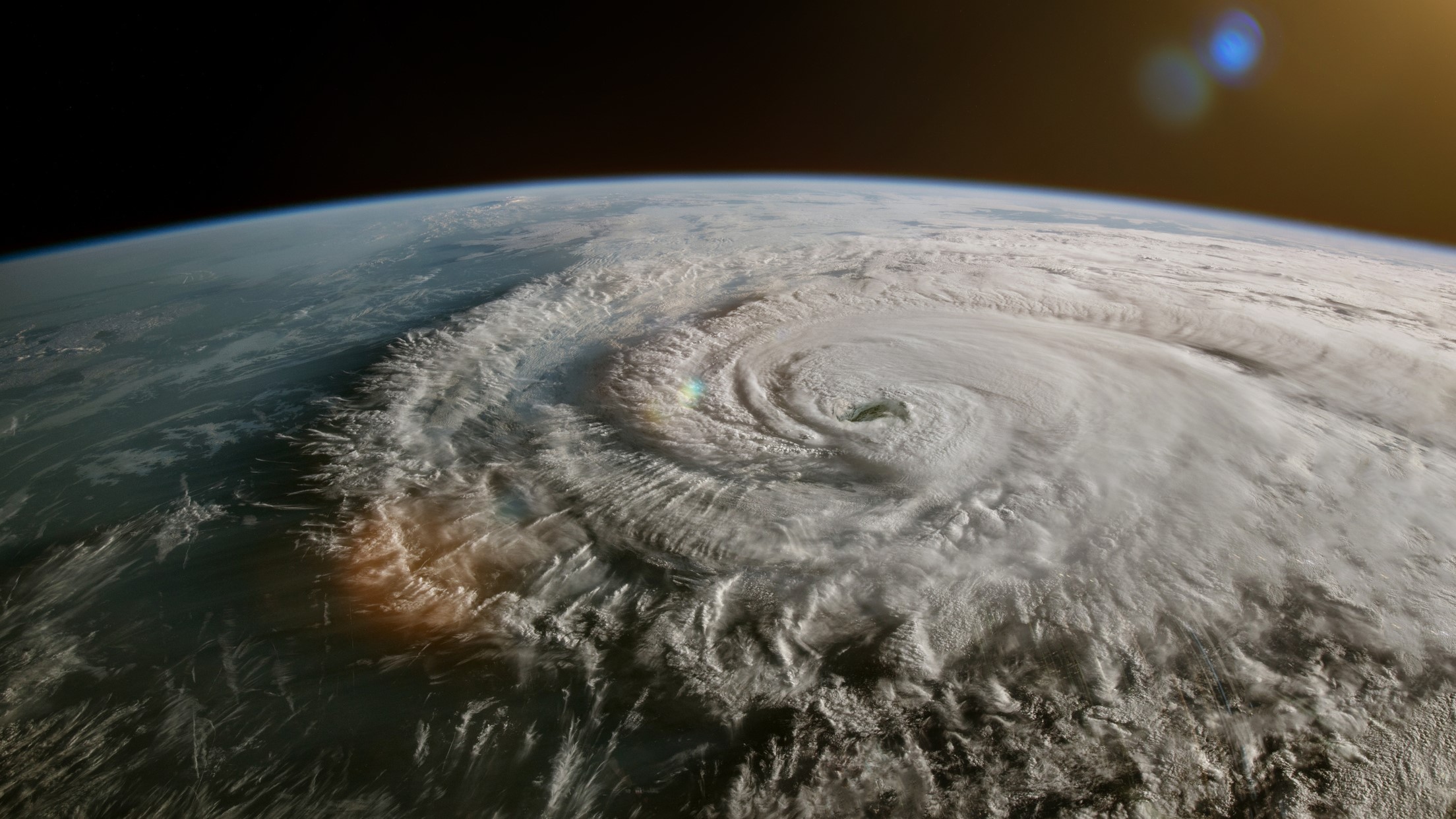

The 1970 Bhola cyclone

This tropical cyclone hit what is now Bangladesh (then East Pakistan) on Nov. 12-13, 1970. According to NOAA's Hurricane Research Division, the storm's strongest wind speeds measured 130 mph (205 km/h), making it the equivalent of a Category 4 major hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane scale. Ahead of its landfall, a 35-foot (10.6 m) storm surge washed over the low-lying islands bordering the Bay of Bengal, causing widespread flooding.

The storm surge, combined with a lack of evacuation, resulted in a massive death toll estimated at 300,000 to 500,000 people. A 1971 report from the National Hurricane Center and the Pakistan Meteorological Department acknowledged the challenge of accurately estimating the death toll, especially due to the influx of seasonal workers who were in the area for the rice harvest. As of the writing of this article, the Bhola cyclone is considered the deadliest tropical cyclone on record, according to the World Meteorological Organization. And it caused an estimated $86 billion in damages.

The 1556 Shaanxi earthquake

The deadliest earthquake in history hit China's Shaanxi province on Jan. 23, 1556. Known as the "Jiajing Great Earthquake" after the emperor whose reign it occurred in, the temblor reduced a 621-square-mile (1,000 square kilometers) swath of the country to rubble, according to the Science Museums of China. An estimated 830,000 people died as their yaodong — cave homes carved into the region's loess plateaus — collapsed. The exact magnitude of the quake is lost to history, but modern-day geophysicists estimate it at around magnitude 8.

The 1887 Yellow River flood

The Yellow River (Huang He) in China was precariously situated far above most of the land around it in the late 1880s, thanks to a series of dikes built to contain the river as it flowed through the farmland of central China. Over time, these dikes had silted up, gradually lifting the river in elevation. When heavy rains swelled the river in September 1887, it spilled over these dikes into the surrounding low-lying land, inundating 5,000 square miles (12,949 square km), according to "Encyclopedia of Disasters: Environmental Catastrophes and Human Tragedies" (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2008). As a result of this flood, an estimated 900,000 to 2 million people lost their lives.

The 1931 Yangtze River floods

Excessive rainfall over central China in July and August of 1931 triggered the most deadly natural disaster in world history — the Central China floods of 1931. The Yangtze River overtopped its banks as spring snowmelt mingled with the over 24 inches (600 millimeters) of rain that fell during the month of July alone. (The Yellow River and other large waterways also reached high levels.) According to "The Nature of Disaster in China: The 1931 Yangzi River Flood" (Cambridge University Press, 2018), the flood inundated almost 70,000 square miles (180,000 square km) and turned the Yangtze into what looked like a giant lake or ocean. Contemporary government numbers put the number of dead at around 2 million, but other agencies, including NOAA, say it may have been as many as 3.7 million people.

Additional resources

For more on natural disasters check out DK's Eyewitness Books "Natural Disasters: Confront the Awesome Power of Nature from Earthquakes and Tsunamis to Hurricanes" and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention page "Natural Disasters and Severe Weather".

Bibliography

Nicholas N. Ambraseys, “The 12th century seismic paroxysm in the Middle East: a historical perspective”, Annal of Geophysics, Volume 47, June 2004.

Walter Kutschera, “On the enigma of dating the Minoan eruption of Santorini”, Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences, Volume 117, April 2020, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2004243117

U.S. Geological Survey, “Earthquakes with 1,000 or More Deaths 1900-2014”, February 2015.

Mischa Meier, “Natural Disasters in the Chronographia ofJohn Malalas: Reflections on their Function—An Initial Sketch”, The Medieval History Journal, Volume 10, 2007

NOAA, OAR, Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, "175th Anniversary of the Coringa cyclone", November 2014.

Athena Kolbe, et al, "Mortality, crime and access to basic needs before and after the Haiti earthquake: a random survey of Port-au-Prince households", Medicine, Conflict and Survival, Volume 26, December 2010, https://doi.org/10.1080/13623699.2010.535279

Angus Gynn, "Encyclopedia of Disasters: Environmental Catastrophes and Human Tragedies", Greenwood Publishing Group, December 2007.

Chris Courtney, "The Nature of Disaster in China: The 1931 Yangzi River Flood", University of Cambridge Press, February 2018, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108278362.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

- Sascha PareStaff writer