Weird Animal Facts

Creature trivia to share with your friends and family

There are thought to be somewhere between 5 million and 100 million species of plants and animals on Earth, but science has only identified about 2 million, according to the National Science Foundation. If we can find all the animals, there will probably be about 7.7 million species of them. That's way too many to account for here. So we dug up some of the most fascinating, little-known facts about various citizens of Kingdom Animalia. A taste of what you'll find inside:

Can cats bark? (Surprisingly, we found one that can.) And what do dogs dream about?

How high can frogs jump? (The answer will shock you.)

Do Fish Sleep? Wait till you hear the rest of the story!

Click in and read on!

Editor's Note: This article was originally published in 2011. In 2016 we updated it and added additional weird facts.

Cats can bark

Dogs bark and cats meow. Simple as that... or so you thought.

It turns out that cats have such similar anatomy to dogs that there's nothing stopping them from barking too. To turn their vocalizations doggish, all cats have to do is push air through their vocal cords with greater than normal force. According to experts, the barking cat in the video above probably learned its unusual, though not unheard of, vocal patterns from a dog co-pet. [Read more about the barking cat]

Dogs can dream

First questions first: Do dogs dream? Almost surely, scientists say. Studies show that rats dream, and researchers figure the act is probably common among mammals.

So, then, about what do dogs dream?

"Dogs dream doggy things," said Stanley Coren, author of "Do Dogs Dream? Nearly Everything Your Dog Wants You to Know" (Norton, 2012), and a professor emeritus of psychology at the University of British Columbia. "So, pointers will point at dream birds, and Dobermans will chase dream burglars,” Coren told us for a story about all this.

Frogs can jump really high

The Southern cricket frog can jump to a height of 60 times its body length. That's like a person jumping a 38 story building.

Frogs at the Calaveras County Fair and Jumping Frog Jubilee in Angels Camp, Calif. are known to hop 7.2 feet (2.2 meters).

Chickens can undergo natural sex changes

All it takes is one dysfunctional ovary to turn a hen into a rooster.

Two sex organs are present when a female chicken is an embryo. But once its sex genes kick in, only the left one develops into an ovary. The right, sexless gonad typically remains dormant.

Most hens make do with just the one ovary, and live out their lives as mothers and egg-layers. However, medical malfunctions such as an ovarian cyst or tumor can cause a hen's left ovary to regress. In its absence, the dormant right sex organ may begin to develop. If it becomes a testical, or a combination ovary-testical, it will emit androgen a male sex hormone. This induces a chicken sex change.

Recently, a hen named Gertie belonging to Jim and Jeanette Howard of Huntingdon, England, spontaneously transitioned into a rooster. It developed a wattle and cockscomb, put on weight, and began strutting and crowing in a notably masculine manner. The Howards renamed Gertie Bertie. [Read more about chicken sex changes]

Rats are ticklish

Ticklishness, a trait that was long thought to be unique to humans and our closest primate relatives, as a means of social bonding: It engenders light-hearted interactions between parents and children, as well as helping youngsters hone their self-defense skills during tickle battles with siblings.

Over the past decade, animal behaviorists have gathered considerable evidence that suggests rats, of all creatures, are ticklish too. When stroked in certain body regions, the rodents emit high-pitched chirps. These chirps seem to signify joy, because the rats will run mazes and press levers if they learn they'll be rewarded with a good tickle afterward. Rats' chirping, the researchers say, is akin to human laughter.

Ticklishness probably evolved in rats for similar reasons that it evolved in apes. Rats are extremely playful animals, engaging in rough-and-tumble play as juveniles just as young apes do, chirping all the while.

Fish sleep... sometimes not enough

Not only do fish sleep, they even suffer from insomnia.

Take the zebrafish, for example a species commonly found in aquariums. When the little swimmers go to sleep for the night, they droop their tails and sink to the bottom of their tanks. Studies on their sleep patterns have shown that if they're kept awake at night, zebrafish seem groggy, unable to learn as quickly as they can during the day.

One study found that zebrafish with faulty hypocretin receptors the same issue that sometimes leads to sleep problems in humans slept, on average, 30 percent less than normal specimens.

Is fatigue a feeling? [Read more about sleepy fish]

Scorpions glow in the dark

Not only do they equip themselves with pincers, poisonous whips for tails, and full body armor, scorpions can even scare the heck out of any reasonable person by glowing in the dark.

When illuminated by ultraviolet rays from a black light, the armored arachnids glow an unnatural neon blue. UV light that hits these creepy crawlies gets converted by proteins in their exoskeletons into light of a blue hue, which is visible to the human eye. Arachnologists have spent untold hours trying to figure out what this fluorescence is good for. Recent research suggests it may be their way of gauging the amount of moonlight shining down on them. Scorpions are nocturnal, light-abhorring creatures. They prefer to lie low on brightly lit nights. [Read more about this theory ]

Penguins do the wave

For penguins trying to survive a harsh Antarctic winter, huddling is a matter of life or death. Birds within a colony crowd together so tightly that individual movements are impossible. Collective movements are a must, however: The penguins on the periphery would die of cold if they weren't continuously being reshuffled toward the center of the crowd. To achieve continual reorganization, the million-member huddle does the wave. In the same way that sound waves propagate through a fluid only much more slowly each penguin takes a tiny, 2- to 4-inch-long step, and the traveling wave of small steps leads to large-scale reshuffling.

Penguins are much better at "going with the flow" than humans, who also tend to move in waves when packed together in large, dense crowds, but sometimes end up getting crushed. No one knows why waves are turbulent and dangerous in a human crowd, but perfectly civil in a penguin one. [Read more about the physics of penguin waves]

A world of weird penises

Kingdom Animalia is full of insane penises. Take the Argentine Lake Duck's 17-inch member, for example: it's longer than the bird itself. That's not as long as the truly huge penises of barnacles yes, those rock-like creatures affixed to ships. Pythons have double-headed penises, while those of the echidna, a small mammal, are four-headed. Check out the bean weevil's viciously spiked penis, which scars female sex partners for life, as well as other outrageously weird animal penises, here.

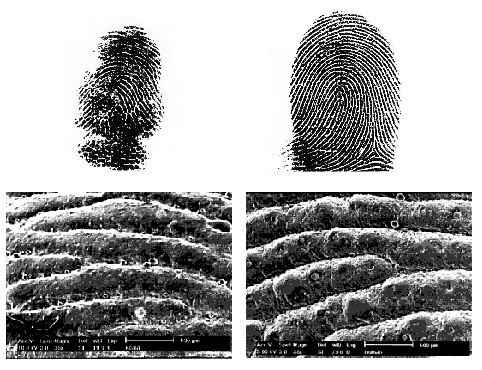

Koalas have human-like fingerprints

Koalas, doll-sized marsupials that climb trees with babies on their backs, have fingerprints that are almost identical to human ones. Not even careful analysis under a microscope can easily distinguish the loopy, whirling ridges on koalas' fingers from our own.

Close human relatives such as chimps and gorillas have fingerprints as well. The remarkable thing about koala prints is that they seem to have evolved independently from the others. On the tree of life, primates and modern koalas' marsupial ancestors branched apart 70 million years ago. Scientists think the koala's fingertip features developed much more recently in its evolutionary history, because its close relatives (such as wombats and kangaroos) lack them.

The fact that primates and koalas separately evolved fingerprints reveals the feature's anatomical purpose. The lifestyles of both koalas and primates require a lot of hand-grasping, both for eating and climbing. It seems that the multidirectional ridges on our fingers evolved to help us grasp. [Read more about koala fingerprints]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.