How to Call Space Station Astronauts on the Radio

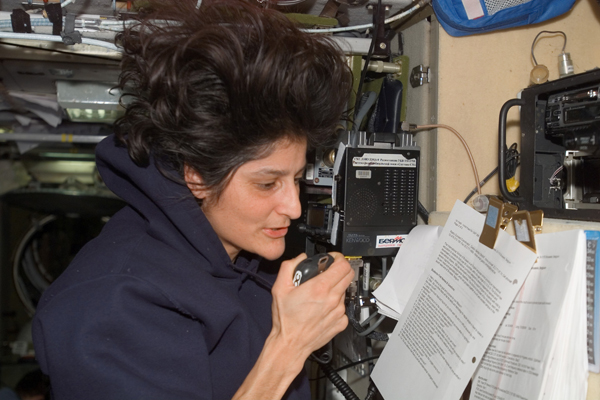

Want to talk to an astronaut in space? Thanks to the Amateur Radio on the International Space Station (ARISS) program, you may be able to. There's a ham radio on board the space station, and about 45 times a year, crew members tune in and hold Q&A sessions with groups of people (usually students) from around the world.

Kenneth Ransom, NASA's ham radio project engineer, explained how the sessions work. "It's very similar to any other type of two-way radio communication. We have a 2-meter radio on board the ISS, and when it's in range of a ground station for approximately 10 minutes as it passes overhead the two can communicate," Ransom told Life's Little Mysteries.

A ground station contains a device capable of both transmitting and receiving radio waves near the 145 megahertz frequency. The ISS radio transmits signals at 145.80 MHz and receives signals at either 144.49 or 145.20 MHz, depending on its orbital location.

Most school groups chosen to participate in the ARISS program set up a temporary ground station in their schools, often with the help of local amateur radio volunteers. When this isn't possible, a school group calls into a ground station, and the back-and-forth radio communications with the space station are relayed to the group over the phone.

"It's more fun when it's direct because you can imagine the space station passing overhead," Ransom said.

During the 10-minute communication sessions, Ransom said, students usually ask the ISS crew what they do in their free time, where they are and what it looks like out their window. "They used to ask if crewmembers had Internet access on board. Now people are aware that they do, because crewmembers Tweet and post photos a lot."

The International Space Station crew members also are often asked what they studied in school and what other people should study if they want to fly in space someday. These questions are very much in the spirit of the ARISS program, which aims to inspire kids to take an interest in math and science. It also follows NASA's tradition of involving schoolchildren; the space shuttle Endeavour was named by elementary school students .

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The radio chats are a rewarding experience for the men and women in orbit, too. "A lot of the crew members enjoy it a lot," Ransom said. "In fact, some of them will even play on the ham radio in their free time." [Do Astronauts Take iPods to Space? ]

Ham (or amateur) radios are communication devices sometimes called "transceivers" because they can both transmit and receive signals used for recreational and noncommercial purposes. Various frequency bands throughout the radiofrequency spectrum (which ranges from 3 kHz to 300 GHz) are reserved for use by ham radios; worldwide, an estimated 2 million people own and operate them.

As mentioned above, the transceiver on board the ISS is tuned to transmit radio signals at a frequency of 145.80 MHz. "Anybody with a receiver or scanner able to tune into that frequency can listen to the space station when it's overhead," Ransom said. "It'll usually be silent, but every so often you can hear the astronauts talking to somebody."

Apply to the ARISS program to win the chance for you or your kids to talk back. In the United States, NASA's Teaching from Space office manages the proposal-and-selection process.

- 6 Everyday Things that Happen Strangely In Space

- What Will NASA Astronauts Do Without Any Space Shuttles?

- What's It Like to Live in Space?

Follow Natalie Wolchover on Twitter @nattyover. Follow Life's Little Mysteries on Twitter @llmysteries, then join us on Facebook.

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science from 2010 to 2012 and is currently a senior physics writer and editor for Quanta Magazine. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with the staff of Quanta, Wolchover won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory writing for her work on the building of the James Webb Space Telescope. Her work has also appeared in the The Best American Science and Nature Writing and The Best Writing on Mathematics, Nature, The New Yorker and Popular Science. She was the 2016 winner of the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award, an annual prize for young science journalists, as well as the winner of the 2017 Science Communication Award for the American Institute of Physics.