The Greatest Mysteries of Neptune

Each week, Life's Little Mysteries presents The Greatest Mysteries of the Cosmos, starting with the coolest things in our solar system.

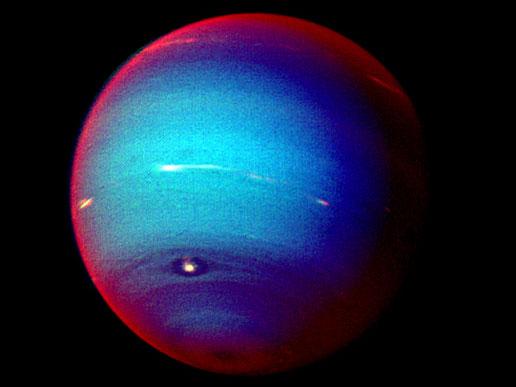

Back in 1846, when European astronomers quarreled over what to call a newly found eighth planet, they eventually settled on Neptune, after the Roman god of the sea. The name turned out to be spot-on, for Neptune, as we know in far better detail now, is colored a deep oceanic blue, with white flecks and deeper blues playing across its clouds.

Along with Uranus, astronomers classify Neptune as an "ice giant" a large world, four times Earth's diameter, with a thick atmosphere of mostly hydrogen and helium along with some water, ammonia and other substances.

If Uranus seems far away at 1.76 billion miles from the sun, Neptune is another billion miles away some 30 times as far away from the Sun as the Earth. Studying Neptune is, as one might imagine, very difficult. [How Far Is It to the Edge of the Solar System? ]

"Neptune is at the edge of our ability to detect with ground-based telescopes, and also [the] Hubble [Space Telescope]," said Heidi Hammel, executive vice president of the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA), a non-profit organization based in Washington, D.C.

The only up-close look we have ever had of Neptune came back in 1989, courtesy of a Voyager 2 flyby. The spacecraft's investigation brought to light many enduring mysteries, which include:

A hyperactive atmosphere

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Astronomers had expected Neptune to look rather boring a weatherless, featureless world in deep freeze. Instead, Voyager revealed a turbulent atmosphere with lighter cloud ripples and raging storms, including one dubbed the Great Dark Spot. Surprisingly, the fastest winds ever recorded in the solar system whirl on Neptune, up around 1,300 miles (about 2,100 kilometers) per hour.

Driving this meteorological activity appears to be Neptune's internal heat, which measures possibly hotter than Uranus. "As you go further from the sun, Jupiter, Saturn and Uranus are each colder in their upper atmosphere," Hammel said. "But when you get to Neptune, it's just as warm as Uranus." (Relatively speaking, of course both planets chill in the range of -355 degrees Fahrenheit (-215 degrees Celsius).) [How Hot Is Hell? ]

Typical planetary heat sources, including leftover internal heat from formation and the decay of radioactive elements, could possibly account for Neptune's temperature. Maybe Neptune is normal and Uranus is the weirdo. "It could be that Uranus is unusually cold," Hammel said.

Clumpy rings

Neptune, like its giant planet brethren of Jupiter , Saturn and Uranus, has a ring system. But rather than distinct hula hoop-like structures, Neptune's rings are perplexing chunky, with gobs of material forming arcs in the outer ring. "These clumps are places where a whole lot of ring particles are stuck together," said Hammel.

Gravitational influences from small moons might cause the regular gumming-up of the rings. But observations by Hammel and colleagues in recent years show that this mechanism appears too tidy. "The locations of the arcs relative to one another have changed in ways we really don't understand," Hammel told Life's Little Mysteries.

Off-kilter magnetic field

When Voyager 2 detected an odd magnetic field at Uranus , scientists figured whatever collision had knocked that planet on its side had similarly scrambled its magnetic field production. Yet when Voyager 2 measured Neptune's field, it also originated from a region away from the world's heart, and nor did it align with planetary rotation as other described magnetic fields do.

"No one expected these magnetic fields offset from the center of the planet and tilted at these crazy angles," said Hammel.

The best theory, Hammel said, is that the magnetic field is generated not in the core of Neptune as it is in the Earth, Jupiter and other planets. Rather, the field emanates from an electrically conductive layer between the core and surface a "mantle of briny water," Hammel speculated, under extreme pressure and unlike any water here on Earth.

Bonus boggler: A captured, feisty moon?

Of Neptune's 13 moons, Triton is by far the biggest and the only one massive enough to be spheroidal. Weirdly, Triton has a "retrograde" orbit, revolving in the opposite direction of the planet and other moons. Plus, the orbit is at an angle rather than in the plane around the equator like typical satellites.

These traits suggest Triton did not form around Neptune. Instead, the planet's gravity probably captured wayward Triton, a passing icy and rocky body from the Kuiper Belt, a band of bodies including Pluto beyond Neptune's realm. "The leading theory is this capture hypothesis," said Candice Hansen, a senior scientist at the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, Ariz.

When Voyager 2 zoomed past Neptune, Hansen was on hand to see the first images, including those of Triton, which turned out to have geyser-like eruptions on its surface. "We were astounded to see those active plumes," Hansen told Life's Little Mysteries.

What powers those plumes isn't Triton's only mystery. Its young surface is not as thoroughly hammered by craters as one would expect, pointing to geological activity that erased early craters. Triton also has intriguing and unique terrain textured like a cantaloupe.

Follow Life's Little Mysteries on Twitter @llmysteries, then join us on Facebook.