10 species our population explosion will likely kill off

Intro

On or around October 31, 2011, the human population will reach the 7 billion mark, according to projections by the United Nations Population Division. Over the years, as our numbers have increased, the populations of the Earth's other inhabitants has steadily decreased; many species have even gone extinct. Habitat loss, pollution, global warming, overfishing and overhunting all of which are connected to the human population explosion are some of the prime reasons for the current and future loss of species.

Some biologists believe that with the current rate of extinction, the Earth will experience its sixth mass extinction, where 75 percent of the planet's species disappear in a geologically short period of time, within the next 300 to 2,000 years.

Here are 10 endangered species that the growing population and expanding range of humans will likely kill off long before the mass extinction event hits.

The Black-Footed Ferret

The black-footed ferret (Mustela nigripes), North America's only native ferret, has long been one of the world's most endangered species. In the late 1900s, there was a national effort in the United States to rid prairies and grasslands of prairie dogs, a type of burrowing rodent that can reduce crop yields and create hazardous holes in the ground. However, these efforts inadvertently caused a dramatic decline in the population of the black-footed ferret, whose diet is 90 percent prairie dog. Human development, which cut the ferret's grassland habitat to less than 2 percent of its original size, also had a major impact on the animal's population, as did disease.

In 1986, scientists believed that there were only 18 black-footed ferrets left in the wild, but breeding programs have helped the ferret's population steadily climb to around 1,000 since then. The black-footed ferret still remains on the brink of extinction and its survival depends largely on the preservation of its now fractured habitat.

Mekong Giant Catfish

With some individuals stretching passed 10 feet long and weighing more than 600 pounds, the Mekong giant catfish (Pangasianodon gigas) holds the Guinness World Record for the largest freshwater fish ever caught. But while it may be physically large, its population is anything but: the number of wild Mekong giant catfish has declined by around 90 percent in the last decade and some experts believe that there are fewer than 300 of the behemoths left. [Why Do Dead Fish Float? ]

Once spanning almost the entire Mekong River, the Mekong giant catfish is now only found in the lower half of the river, in Cambodia, Laos, Thailand and Vietnam. Overfishing has played a major role in the fish's decline, but alterations to the fish's habitat including the construction of dams that block migration routes, and the destruction of spawning and breeding grounds are also to blame. River development projects, along with current ineffective bans on fishing, may soon spell the doom of this record-holder. [Can a Goldfish Really Grow to 30 Pounds? ]

Vaquita

With a population of fewer than 300 individuals, the vaquita porpoise (Phocoena sinusis) is the world's smallest and most endangered cetacean, a group of marine mammals that includes whales, dolphins and porpoises. The vaquita, which means "little cow" in Spanish, also has the most limited habitat of all cetaceans it is only found in the northern extremes of the Gulf of California.

Until recently, the greatest threat to the vaquita has been gillnets set for mackerel and sharks. In 2000, Mexico's International Committee for the Recovery of the Vaquita estimated that the 1,300 gillnets were killing between 39 and 84 of the porpoises each year. Recently, the Mexican government and the tourism and fishing industries cut the number of gillnets in the gulf by 80 percent, drastically reducing the number of vaquita killed each year as bycatch.

However, even if the number of net-caught vaquitas is reduced to zero, other dangers, such as chlorinated pesticides, still pose a major threat to the survival of this rare marine mammal. The vaquita will likely follow the path of another small cetacean, the baiji, which researchers declared extinct in 2006.

Hine's Emerald Dragonfly

People generally don't think of insects as being in danger of extinction, but the populations of many bug species around the world are dwindling and may disappear soon. One such insect is the Hine's emerald dragonfly (Somatochlora hineana), which is distinguished by its light green eyes and pair of yellow stripes on its sides. The Hine's emerald is the only dragonfly on the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's endangered species list.

Historically, you could find the rare insect in various spring-fed wetland marshes and sedge meadows throughout Ohio, Alabama and Indiana, but these days the dragonfly only exists in small areas in Illinois, Wisconsin, Missouri and Michigan. The major cause of the dragonfly's decline is the loss of its wetland habitats, which have been and still are drained and filled for urban and industrial projects. Groundwater pollutants like pesticides are also adding to the dragonfly's increasingly bleak outlook.

Ozark Hellbender

The Ozark hellbender (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis bishop) is one of the newest editions to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's endangered species list. The giant salamander is North America's largest amphibian, and its population has declined 75 percent in the last few decades, leaving less than 600 individuals left in the wild.

Found only in rivers and streams in northern Arkansas and southern Missouri, the Ozark hellbender's population has greatly suffered in the past because of the illegal pet trade industry. But there are many other factors contributing to the salamander's spiraling numbers, including habitat loss, mining, sedimentation, and poor water quality, partly caused by the introduction of chemicals and hormones like estrogen, which affect the Ozark's reproduction rates. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimates that the Ozark hellbender will face extinction within the next 20 years.

Gharial

The last surviving member of the Gavialidae family of crocodilians, the gharial (Gavialis gangeticus) resembles its crocodile cousins but has a long, slender snout. In the mid-1900s, the gharial population rested somewhere between 5,000 and 10,000 individuals; nowadays, there are only around 1,500 individuals left in the wild, and less than 200 of them are breeding adults.

The gharial was once common throughout the river systems of India, Nepal, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan and Myanmar, but it's now virtually extinct in all of those countries except India and Nepal, where its range has shrunk by 98 percent. The gharial's drastic population decline is largely due to people, who hunted the reptile extensively for skins, trophies and indigenous medicine, and collected their eggs for meals.

Conservationists no longer see hunting as a significant threat to the gharial, though excessive, irreversible habitat loss from such things as dams, artificial embankments, irrigation canals and sand mining continue to confound the gharial's survival. [What's the Difference Between Alligators and Crocodiles? ]

Hainan black crested gibbon

Found only on Hainan Island, China, the Hainan black crested gibbon, or Hainan gibbon (Nomascus hainanus), is one of the most critically endangered primates in the world. Before 1960, there were more than 2,000 Hainan gibbons located across Hainan Island, but in 2003 researchers could only find 13 individuals confined to a small region called the Bawangling Natural Reserve. Today, the Hainan gibbon population likely stands at little more than 20 individuals.

Hunting and habitat loss have been the major players in the decline of the Hainan gibbon. In the 1960s, much of Hainan's lowland rainforest were converted to rubber plantations, forcing the gibbons to retreat to higher elevations, where there's less food suitable to their diet. Hainan gibbons may also be indirectly disturbed by the growing human population on the island, which increased 330 percent between 1960 and 2003, according to a recent study. Road and hydropower station construction, along with road traffic and plantation activity, all negatively impact Hainan gibbon behavior, threatening the primate's long-term survival.

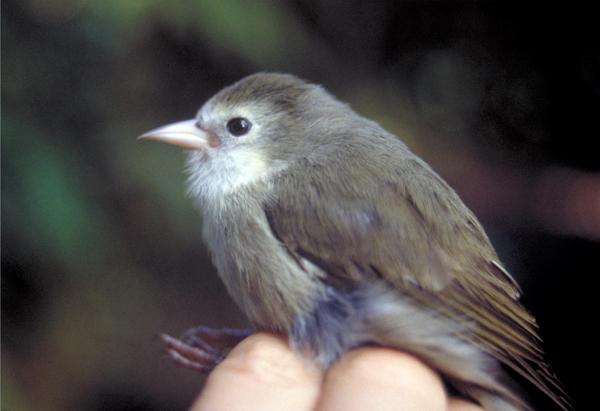

?Akikiki

The ?Akikiki, or Kaua?i creeper (Oreomystis bairdi), is a critically endangered songbird endemic to the island of Kaua?i in Hawai?i. A bird survey in 2000 estimated that there are around 1,500 Kaua?i creepers left in the wild, though the bird's population continues to decline.

Before Europeans arrived in Hawai?i in 1778, there were at least 71 endemic bird species; 26 species are now extinct, with another 32 listed as either endangered or threatened (near endangered), according to the American Bird Conservancy. With the arrival of Europeans, the ?Akikiki, like other native bird species in Hawai?i, suffered from diseases picked up from mosquitoes and exotic bird species the sailors introduced to the islands. The Kaua?i creeper may have also been impacted by habitat degradation caused by feral pigs and goats (also brought by Europeans) and predation by rats, cats and other new species. [More Birds Endangered Than Ever]

Today, the Kaua?i creeper's major threat may be the changing climate the Endangered Species Coalition named the bird one of America's top ten threatened species impacted by global warming. Because of cool forest temperatures in the ?Akikiki's home, the Alaka'i Wilderness Preserve, the bird currently has a safe haven from malaria transmission; however, the coalition points out that a mere 4 degree F increase in temperature of island's forests would cut these shielded areas by 85 percent.

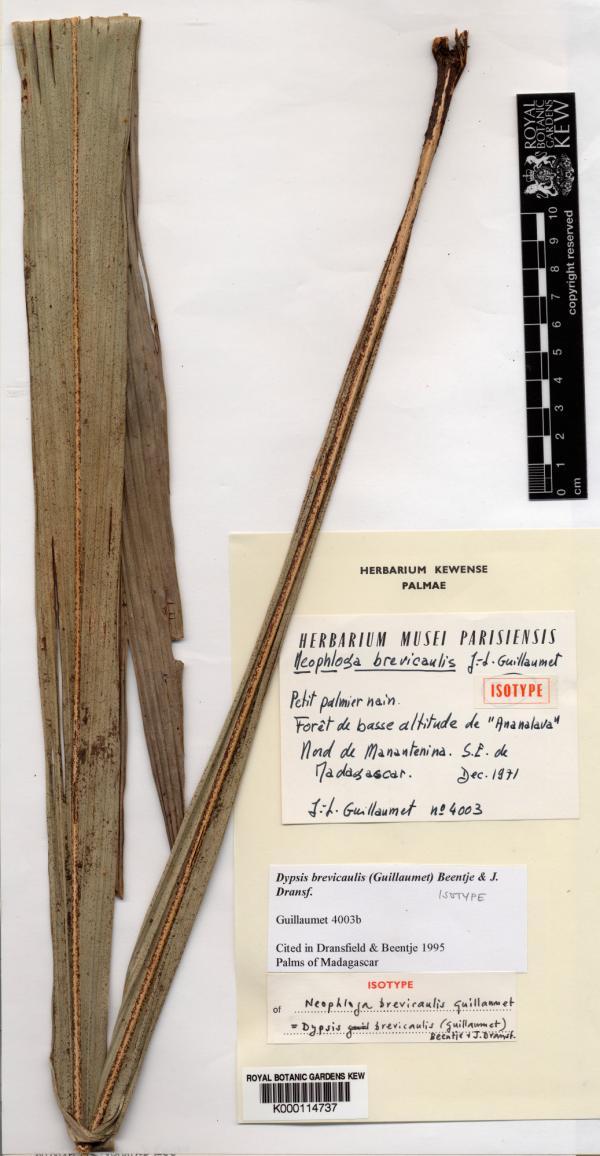

Dypsis brevicaulis

Dypsis brevicaulis is a dwarf palm tree with leaves that appear to grow directly out of the ground (hence "brevicaulis," Latin for "stort-stemmed"). First discovered in 1973, Dypsis brevicaulis is a native to the extreme southeast forest of Madagascar, where it grows in white sand or laterite, a type of soil rich in iron or aluminum. Dypsis brevicaulis only lives in three sites in the forest, and fewer than fifty of the plants have ever been seen in the wild.

Dypsis brevicaulis' major threat to survival is deforestation local villagers are clearing the palm's natural habitat for cultivation. Additionally, plans to mine for ilmenite, a mineral used to produce titanium dioxide for sun block and other applications, help to ensure the rare palm's future extinction. [Gallery: Plants in Danger]

Elkhorn Coral

With its quick-growing colonies, the elkhorn coral (Acropora palmata) is one of the most important reef-building species in the Caribbean but it's also one of the most endangered. The coral, named so because its branches resembe an elk's horns, was abundant in the Caribbean and Florida Keys prior to 1980, but since then 90 to 95 percent of elkhorn coral has perished. Various diseases, such as the contagious (and elkhorn-specific) white pox disease, are largely behind the species' quick decline. Scientists recently learned that humans are partly to blame: human feces, which seeps into the Florida Keys and the Caribbean from leaky septic tanks, transmits a white pox-causing bacterium to elkhorn coral.

Communities are slowly eliminating white pox disease from the picture by installing advanced wastewater treatment systems, but this does nothing for the elkhorn's and all other coral species' natural enemy, global climate change. Rising sea temperatures cause coral bleaching, which leaves coral weak and even more vulnerable to diseases than normal. In addition, excessive carbon dioxide from the burning of fossil fuels increases ocean acidification, impairing the coral's ability to form a protective skeleton.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.