Could There Be Life on the New Earth-Size Planets?

For life as we know it to arise on another planet, scientists think the alien world must have three key ingredients: organic molecules that can form complex structures, energy to jiggle those molecules, and liquid water for them to jiggle in. It's a short recipe, but nonetheless, only planets that are extremely similar to Earth can possibly have all three items in stock.

If a planet is much closer to its star than we are to ours (and assuming that star is similar in size to our sun), all the water on its surface will evaporate in the heat. If it's much farther away, all its water will freeze. Similarly, planets much larger than Earth are gaseous, with no solid surface for an ocean to slosh around on, while those much smaller wouldn't have had enough gravity to form in the first place. Thus, in the search for "candidate planets" which could host alien life, "alien Earths" are the Holy Grail.

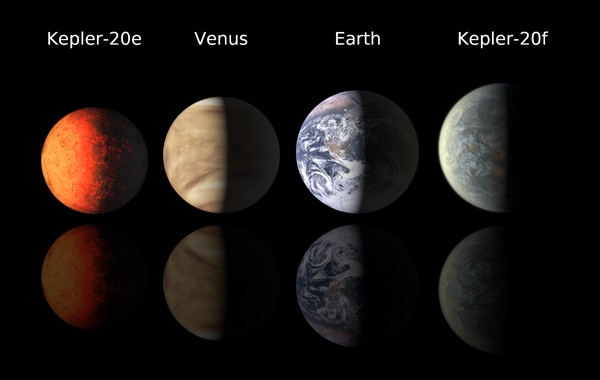

In a paper published today (Dec. 20) in the journal Nature, a team of scientists who study data collected by NASA's Kepler telescope report the discovery of a pair of exoplanets, or planets outside our solar system, that are almost exactly the same size as Earth. The distant worlds, labeled Kepler-20e and 20f, orbit a star called Kepler-20 located 950 light-years away, and have diameters 0.87 times and 1.03 times that of Earth, respectively.

At those sizes, the planets' gravity would be strong enough to make them rocky like Earth, rather than gaseous like Jupiter. "Theoretical models suggest that the material inside the planet could be iron in the core surrounded by a mantle of silicates," said Guillermo Torres, a member of the Kepler team based at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. If that's the case, they would have, respectively, masses 1.7 times and three times Earth's mass, he said. [Infographic: Earth-Size Alien Worlds]

The planets are roughly Earth-size, but do they have what it takes to sustain life? Unfortunately, not quite. "These are just way too hot to be habitable," Torres told Life's Little Mysteries.

Both Kepler-20e and Kepler-20f orbit extremely close to their star, with years just 6 days and 20 days long, respectively. Though their star is slightly dimmer than our own, it still blasts them with too much heat. "For the inner one, the temperature is about 1,000 degrees Celsius [1,800 degrees Fahrenheit], and for the outer one it's about 700 degrees C [1,300 degrees F]," Torres said.

Unfortunately, that's far too hot for liquid water to survive. And because there are no swirling oceans on the new planets no primordial soups for organic molecules to slosh around in there has been no genesis of life there, the scientists say.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But is there any chance that life that doesn't require water could exist on Kepler-20e and 20f? Torres said he gets this question a lot: "Why do we think that life has to be like we have it here on Earth? Well, the thing is we don't have any other examples of life, so we have to start with what we know. We cannot rule out that there might be other types of life that don't require water... if that's possible... but that seems a little far-fetched."

Two weeks ago, the Kepler team announced its discovery of another planet that was close to being habitable, but which missed the mark for a different reason. "We announced Kepler-22b, which has the right temperature for life, but it's too big. Now, we're announcing a planet that's the same size as Earth but it's too hot," said Dave Charbonneau, another member of the Kepler team based at Harvard's CfA.

"What we're doing next is trying to look for a planet that's the best of both worlds: Earth-size and the right temperature. That's the big one," he said.

- A Field Guide to Alien Planets

- How Did Astronomers Find the New Earth-Size Planets?

- Will We Really Find Alien Life Within 20 Years?

Follow Natalie Wolchover on Twitter @nattyover. Follow Life's Little Mysteries on Twitter @llmysteries, then join us on Facebook.

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science from 2010 to 2012 and is currently a senior physics writer and editor for Quanta Magazine. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with the staff of Quanta, Wolchover won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory writing for her work on the building of the James Webb Space Telescope. Her work has also appeared in the The Best American Science and Nature Writing and The Best Writing on Mathematics, Nature, The New Yorker and Popular Science. She was the 2016 winner of the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award, an annual prize for young science journalists, as well as the winner of the 2017 Science Communication Award for the American Institute of Physics.