Does Asteroid Mining Violate Space Law?

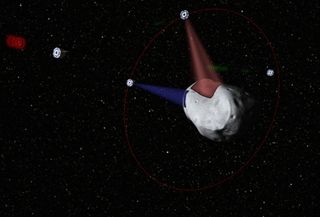

Several well-known billionaires are forming a company with plans to send a robotic spacecraft to mine precious metals from an asteroid and bring them back to Earth. Google executives Larry Page and Eric Schmidt and their business partners say the enterprise will "add trillions to the global GDP."

But to whom do those trillions belong — the company, or everyone? Does a private company have a right to stake claim to an asteroid, or are celestial bodies such as the moon, planets and asteroids the communal property of all Earthlings?

"The law on this is not settled and not clear," said Henry Hertzfeld, professor of space policy and international affairs at George Washington University. "There are lots of opinions on the status here, and nobody is necessarily right because it's complicated."

The legal ambiguity hasn't needed to be addressed before, Hertzfeld said, because no company has previously come forward with a serious asteroid mining mission plan and the funds to back it. When the debate over space property rights is forced to ensue, old international wounds will likely be reopened.

The most pertinent piece of law is the Outer Space Treaty (OST), an agreement signed or ratified by all spacefaring nations in 1967, which established, among other things, that no nation may claim sovereignty over space, the moon or celestial bodies. The treaty was intended to protect the rights of lesser developed nations that did not yet have the ability to explore space, and to prevent the U.S. or the Soviet Union — whichever would go on to win the space race — from claiming sovereignty over the moon. However, the question of space resource exploitation is not explicitly addressed in the treaty, and interpretations of its words vary widely. [Could an Asteroid Destroy Earth?]

Art Dula, a space law professor at the University of Houston, believes private companies absolutely have the right to mine an asteroid. "The 1967 Outer Space Treaty specifically permits the 'use' of outer space by nongovernmental entities. There is no suggestion in the treaty that commercial or business use would be prohibited," Dula told Life's Little Mysteries. In his opinion, the treaty and a subsequent United Nations resolution established that national governments themselves are responsible for regulating the use of outer space of citizens and companies within their borders.

Thus, because the billionaires are American and forming their company in the United States, the U.S. government is charged with giving the go-ahead to the billionaires' bold new project, he said, and the Constitution ensures it will do so. The 10th Amendment — which states that all powers not delegated to the federal government, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the states or to the people — means that the right to mine an asteroid belongs to the people."I am pleased to say that the American people and the corporations they form are presently free to conduct mining operations in outer space for commercial purposes, as this activity has not been made either illegal or regulated by the federal government or the several states," Dula said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Not everyone agrees. Frank Lyall, public law professor at the University of Aberdeen, Scotland, and director of the International Institute of Space Law, and Paul Larsen, a space law expert and adjunct professor at Georgetown Law School, both interpret the OST as meaning that no one — neither a government, nor a person — can claim title to an asteroid, or the precious metals therein.

The point is proven by a 2001 court case, they said. In 2000, an American man named Gregory Nemitz registered a claim to the asteroid Eros. When NASA sent a satellite to investigate this asteroid soon after, Nemitz sent a letter to NASA telling the space agency to pay parking fees for landing the satellite on his property. "NASA declined and so did the U.S. Dept. of State," Larsen explained in an email. "The reason is that the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, Article II, specifically states 'outer space ... is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereign, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.'" [Photos: Planetary Resources' Plan to Tap Space Rock Riches]

Thus, as the international law on the matter now stands, "an asteroid in outer space cannot be mined for the purpose of appropriation," Lyall wrote. "All the states whose nationals might mine are part of the 1967 [Outer Space] Treaty agreement and hence their national systems cannot provide the base of a title to the property."

With such polar opposite interpretations of the existing space law in play, another international agreement may be needed to address the question of space resource exploitation more directly — especially if or when the "Planetary Resources" enterprise becomes a reality. Many issues need to be settled, Hertzfeld said. "For example, how will they do it? How much insurance do they need? Are they allowed to leave junk behind on the asteroid? What would flooding the market with something that is rare on Earth do to the market? (The mined material might not get the market price they think it would because the price theoretically would go down.) So, there are so many issues needing to be addressed."

Nonetheless, in Hertzfeld's opinion, the property rights of corporations will probably ultimately trump the idealistic notion that space is the common property of humankind. "The bottom line is if someone wants to risk the money, take the time, thinks they have a business case, it is probably possible to do it," he said.

And if space resources belong to everyone, then no one is going to develop them anyway, said Dula, who is also confident that a U.S. court case would ultimately end in favor of a private company, granting them the right to mine an asteroid.

"We have to have some sort of system that allows people to develop wealth," he said. "We need these resources, and it's going to be really interesting to see how the law develops as these questions become reality. The other thing is, it costs so much just to get up there. You have to get a gang of billionaires together to even talk about this stuff."

Regardless of where they stand, the experts agree on one thing: The debate over who owns space is going to heat up in the not-too-distant future.

Follow Natalie Wolchover on Twitter @nattyover. Follow Life's Little Mysteries on Twitter @llmysteries and join us on Facebook.

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science from 2010 to 2012 and is currently a senior physics writer and editor for Quanta Magazine. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with the staff of Quanta, Wolchover won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory writing for her work on the building of the James Webb Space Telescope. Her work has also appeared in the The Best American Science and Nature Writing and The Best Writing on Mathematics, Nature, The New Yorker and Popular Science. She was the 2016 winner of the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award, an annual prize for young science journalists, as well as the winner of the 2017 Science Communication Award for the American Institute of Physics.