Why Are Pollen Allergies So Common?

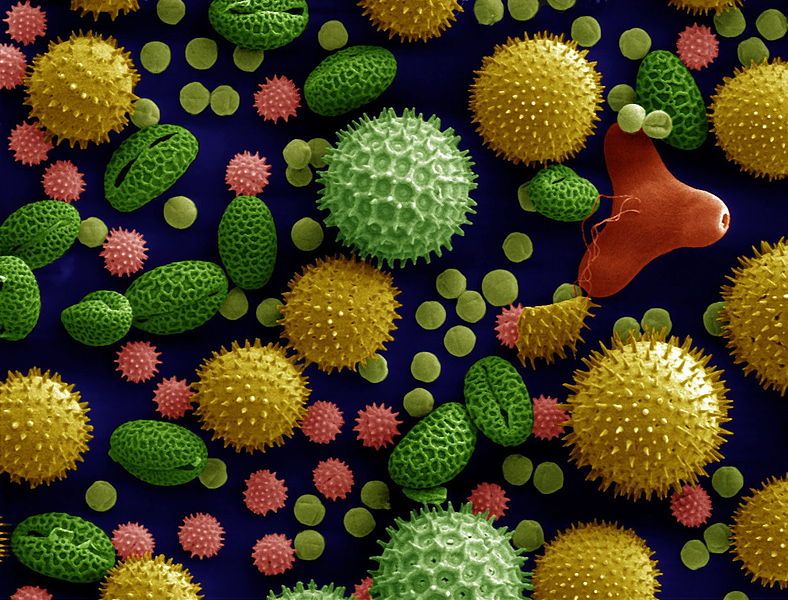

You can't get more natural than plants. Humans have been around them for our entire evolutionary history. So why are roughly 20 percent of Americans allergic to pollen, as if this plant sperm powder were some sort of toxic foreign substance?

The real question, according to Susan Waserman, professor of medicine in the division of clinical immunology and allergy at McMaster University in Canada, is not "Why pollen?" but "Why allergies at all?" Humans typically become allergic to things we're frequently exposed to as children. Pollen is one of those things; in the spring, a cubic meter of air can contain thousands of pollen grains, so we're inhaling them fairly constantly. But we're also routinely exposed to food and pet hair as kids, and we commonly develop allergies to those, too.

So it's not pollen, it's just stuff. "If you've got that genetic tendency to become sensitized" — i.e. to develop allergic reactions to harmless substances — "the huge amount of pollen you breathe in and out can easily lead to sensitization," Waserman told Life's Little Mysteries.

If there's nothing particularly heinous about pollen besides its prevalence, why do we develop allergies in the first place? The way it works is this: Allergies set in when your immune system misjudges a harmless protein, interpreting it as a threat. Once your system has gotten the wrong impression about a cat hair or pollen grain, there's no changing its "mind" — you're stuck with the allergy, often for the rest of your life.

The immune system will raise its defenses every time it detects the presence of the offending substance, or allergen. First, immune cells produce pitchforklike proteins called antibodies. Each antibody picks up an allergen molecule and carries it to white blood cells called mast cells, which trigger the release of chemicals like histamine. Those induce the allergic symptoms we all know and loathe: wheezing, sneezing, itching, swelling and rashes.

But why do immune systems make that fateful mistake in the first place?

There's some evidence that allergies set in when you happen to be exposed to an allergen at the same time that you're fighting off a virus, such as the common cold. "It's entirely plausible that when the body is mounting a big immune response to a virus, that you're going to trigger an allergic response to something you're exposed to at the same time," Waserman said. "But we don't know definitely."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Most studies of children getting "co-infected" by viruses and allergies have focused on pet hair allergies, she said, but the explanation may pertain to the onset of pollen and food allergies, too.

On the other hand, inadequate exposure to bacteria and viruses during early childhood also vastly increases the likelihood that you'll develop allergies. Thanks to modern hygiene — antibacterial soap, clean water, pasteurized milk and more — kids aren't exposed to nearly as many microbes as they used to be. As a result, their immune systems get fewer opportunities to learn how to discriminate between dangerous pathogens and harmless things like pollen. It's called the "hygiene hypothesis," but according to Waserman, it's an accepted theory. "People whose immune systems are no longer busy fighting infection become disregulated and allergic," she said.

Questions remain about why infectious disease exposure sometimes triggers but at other times stifles the onset of allergies, and what the perfect balance of filthiness and cleanliness might be during childhood. In the meantime, when the pollen count goes up on a lovely spring day, one-fifth of us are stuck indoors.

Follow Natalie Wolchover on Twitter @nattyover. Follow Life's Little Mysteries on Twitter @llmysteries, then join us on Facebook.

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science from 2010 to 2012 and is currently a senior physics writer and editor for Quanta Magazine. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with the staff of Quanta, Wolchover won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory writing for her work on the building of the James Webb Space Telescope. Her work has also appeared in the The Best American Science and Nature Writing and The Best Writing on Mathematics, Nature, The New Yorker and Popular Science. She was the 2016 winner of the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award, an annual prize for young science journalists, as well as the winner of the 2017 Science Communication Award for the American Institute of Physics.