3,400 years ago, 'brain surgery' left man with square hole in his skull, ancient bones suggest

A hole in a Late Bronze Age human skull found in northern Israel may be early evidence of trepanation; but other experts argue that the hole could have been made for ritual purposes after the man's death.

The skeletal remains of two Bronze Age brothers buried more than 3,400 years ago in what's now northern Israel reveal that the siblings lived with severe health problems but had access to treatments, including trepanation, a new study suggests.

The older brother had a piece of bone removed from his skull, possibly in an attempt to treat debilitating diseases, the researchers said. The discovery may be among the earliest evidence in this region for the practice of trepanation (also spelled trephination) — making a hole in the skull, hopefully without damaging the brain — which in ancient times was thought to be a treatment for various ailments, according to the study, published online Wednesday (Feb. 22) in the journal PLOS One.

But other experts disagree, saying the holes likely weren't meant to be curative; instead, it's possible that the man's skull was modified for ritual purposes after his death.

Related: The Incas mastered the grisly practice of drilling holes in people's skulls

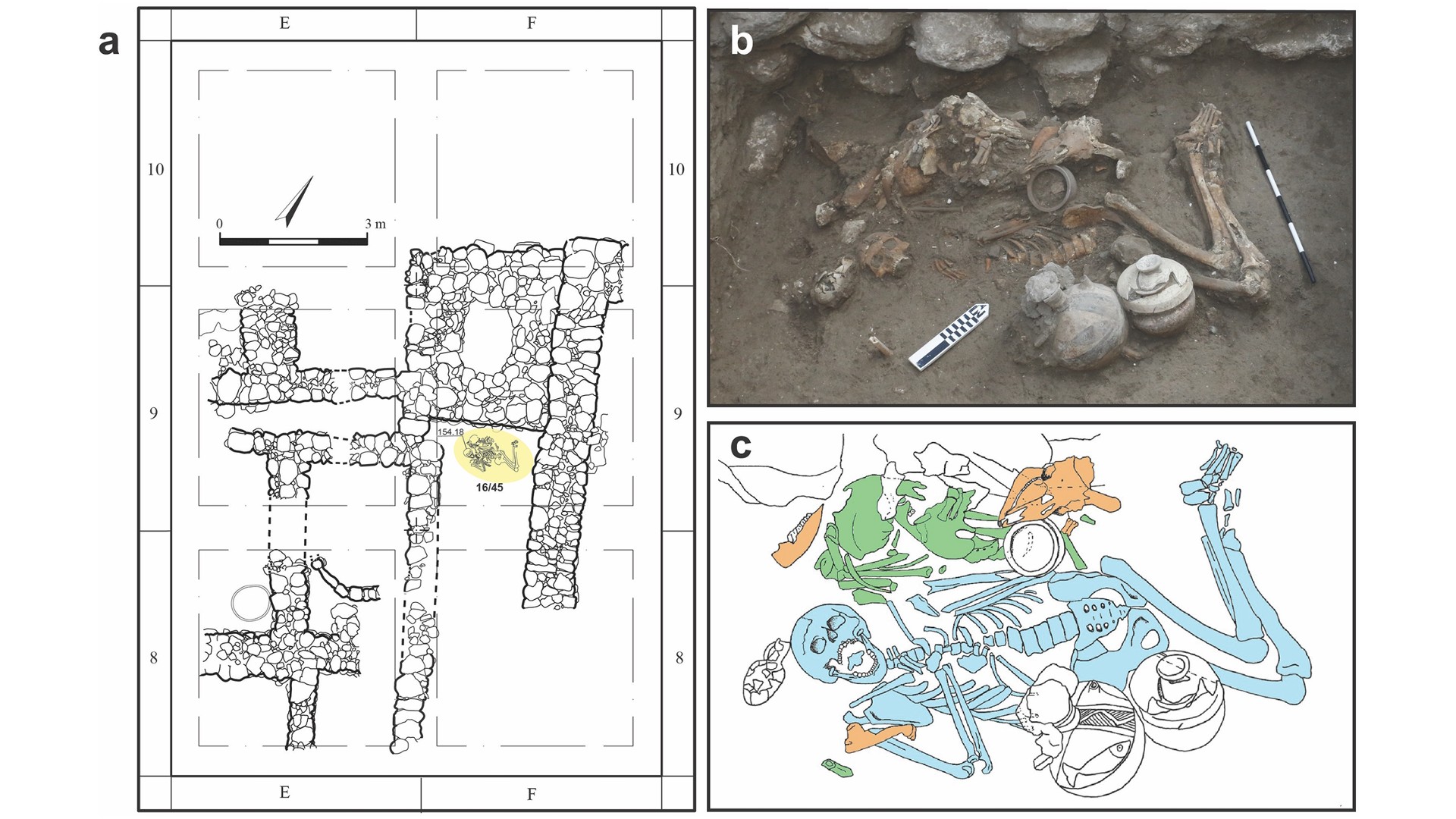

The skeletons were found in 2016 in a tomb at Tel Megiddo, which was the site of a Canaanite city-state in the Late Bronze Age. An analysis of their DNA showed that the men were brothers.

An examination of the skeletons showed that both men suffered from debilitating diseases that destroyed some of their bones and distorted others. It's possible that the men were genetically predisposed to such diseases, which may have included a form of leprosy, study first author Rachel Kalisher, a doctoral student in archaeology at Brown University, told Live Science.

Bronze Age bones

The analysis by Kalisher and her colleagues suggests that the younger brother was in his late teens or early 20s when he died during the Late Bronze Age, between 1550 B.C. and 1450 B.C., and that the older brother was between 21 and 46 years old when he died a few years later.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

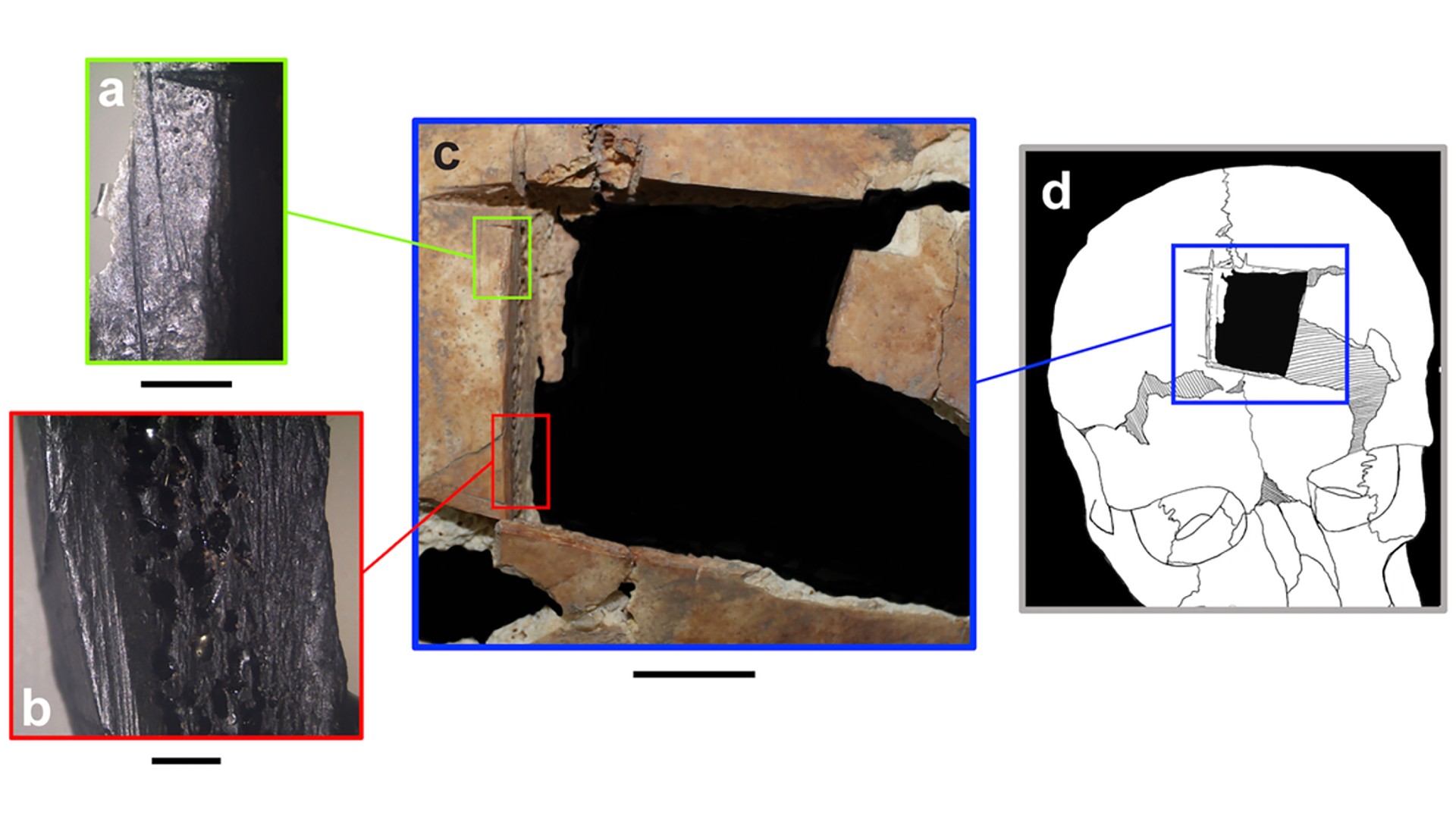

The older brother had a square piece of bone about 1.2 inches (30 millimeters) across removed from his skull. Because the skull shows no signs of healing, the authors proposed that the bone removal occurred about one week before the man's death and that it was a form of trepanation to treat the debilitating conditions he suffered from.

"The totality of evidence is that you have an individual who had suffered illness for a long period of time, and that perhaps it was a decline," Kalisher said. "So perhaps this was some sort of intervention, or a life-saving procedure."

The hole was made by scoring the skull and carefully levering out pieces from the center — a different procedure from circular trepanations, which were usually performed by scraping or drilling, she said. "We have evidence of trepanation in this region that predates the Late Bronze Age, but this example at Megiddo is the earliest in this area of this type of surgery," she said.

Elite burial

Both brothers were buried with fine ceramic vessels and high-quality food offerings, suggesting they were of high social status, and their high status may have been one reason they lived for many years in spite of their debilitating conditions, Kalisher said.

Although Kalisher and her colleagues said the older man's status might have given him access to rare surgical procedures like trepanation, another expert suggested that the square hole indicates the incision was made after his death, possibly for ritualistic purposes.

Israel Hershkovitz, a professor emeritus of anatomy and anthropology at Tel Aviv University, was not involved in the latest research, but he has studied other ancient trepanations in the region.

"It is well accepted that cutting of the skulls which results in straight-line or square openings were most probably not done for therapeutic purposes," he told Live Science in an email. Studies have shown that although circular trepanations might have been done in an attempt to cure an ailment, that did not seem to be the case here, he added.

"The shape of the described trephination is square and the walls vertical," Hershkovitz said. "If this had been done while the individual was alive, it would have led to his immediate death."

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.