Pluto Remains Shrouded in Mystery

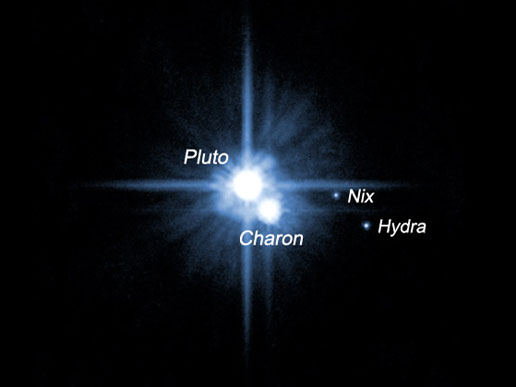

A fifth moon orbiting the dwarf planet Pluto has turned up in new Hubble Space Telescope images. Planetary scientists say the newfound moon serves as yet another reminder of how little we really know about this remote, chaotic world.

"Every time we look harder, we find new stuff," said Alan Stern, a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo., and a member of the moon's discovery team. In recent decades, he and his colleagues have identified signs of an atmosphere on the dwarf planet, as well as polar caps, a high albedo (highly reflective surface), and of course, a growing collection of moons.

But in-depth investigation of Pluto has proven tremendously difficult from 3 billion miles away. The best images we have of the icy world come from the Hubble Telescope, but to the untrained eye, they're not much to behold. At a slim 1,429 miles wide — roughly the distance from Maine to the tip of Florida — Pluto will likely remain a dim blur until NASA's New Horizons spacecraft arrives there in July 2015.

What secrets might lie in wait? [The Greatest Mysteries of the Planets]

For one thing, the dwarf planet could possess a set of everyone's favorite cosmic accessories. "It's a very distinct possibility and the theoretical arguments are very strong that Pluto has rings that come and go with time," Stern told Life's Little Mysteries.

Space rocks and other debris litter the Kuiper belt, where Pluto resides, and they probably pepper the icy world and its moons. "The moons are being hit all the time, and the ejecta [collision debris] escapes, making a ring," Stern said. "And then radiation and gravity depletes the ring through erosion."

Computer models of this cycle suggest that all the dwarf planet's rings sometimes get eroded before a new one forms. "When you model that on a computer there is randomness to [the spacing of the collision events], and so the rings come and go according to these models," he said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Beneath those fleeting rings, and beneath Pluto's thin, nitrogen-rich atmosphere, it's anyone's guess how the surface will appear when viewed up close. In Hubble images, the dwarf planet's mottled façade varies between extremes of charcoal black, dark orange and white. What materials compose these assorted regions? And do they give rise to cold-liquid-spewing cryovolcanoes or geysers? The surface's geochemistry might even hint at a giant underground ocean. [The True Stories of 5 Mystery Planets]

More data is also needed to clarify how Pluto wound up in its frigid Kuiper belt domain. Astronomers think it and its neighbors formed from the same disk of material around the sun that coalesced into the other major bodies in the solar system. But at some point early on, a planetary collision probably sent Pluto ricocheting far beyond the rest, forever to carry the mark of this fateful encounter in the form of its strange, oval path around the sun, which lies off the plane of the other planetary orbits.

Considering all the mysteries that remain, Pluto's newfound moon almost definitely won't be the last of its surprises. "When New Horizons gets there, I think it's going to knock our socks off," Stern said. "It's going to be a whole new world."

Follow Natalie Wolchover on Twitter @nattyover or Life's Little Mysteries @llmysteries. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science from 2010 to 2012 and is currently a senior physics writer and editor for Quanta Magazine. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with the staff of Quanta, Wolchover won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory writing for her work on the building of the James Webb Space Telescope. Her work has also appeared in the The Best American Science and Nature Writing and The Best Writing on Mathematics, Nature, The New Yorker and Popular Science. She was the 2016 winner of the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award, an annual prize for young science journalists, as well as the winner of the 2017 Science Communication Award for the American Institute of Physics.