Hilarious Science: Gallery of the 2012 Ig Nobel Prize Winners

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Ig Nobel Prizes

Every aspiring scientist dreams of someday making a discovery so illustrious that it lands them a spot on the stage of the Nobel Prize Ceremony in Stockholm. Through a weird twist of fate, some instead find themselves wearing a silly hat and being led by a string onto the stage of the Ig Nobel Prize Ceremony in Cambridge, Mass.

The Ig Nobel Prizes, a whimsical spoof of the Nobels held each fall at Harvard University, honors scientists from around the world who have made genuine, but also hilarious, contributions to their fields. The 22nd annual ceremony took place Thursday evening (Sept. 20), and without further ado, here are this year's winners.

Medicine

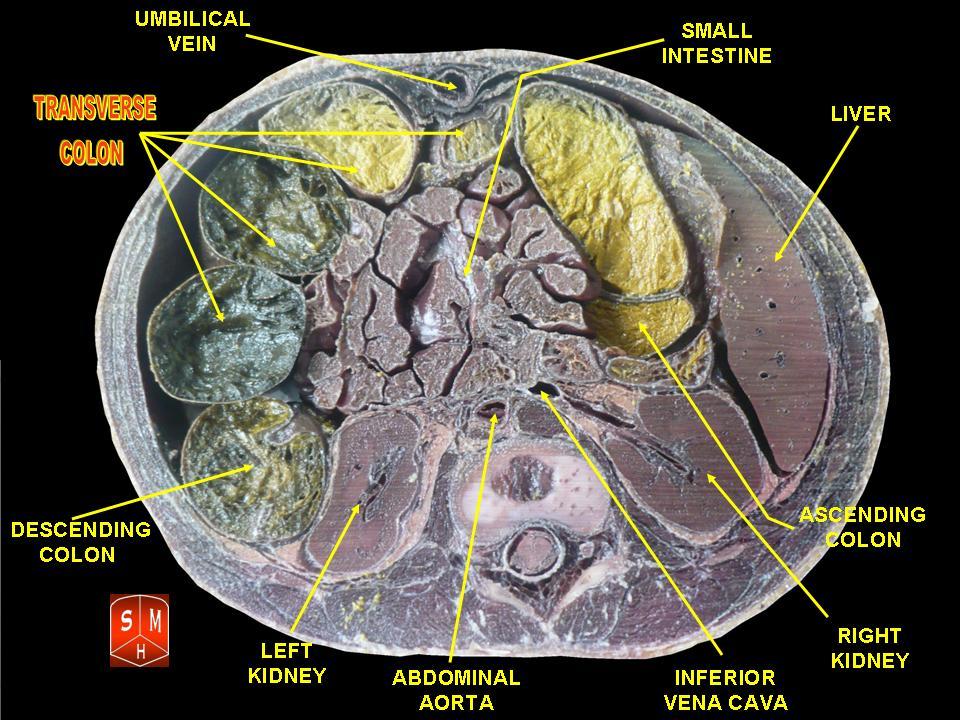

Emmanuel Ben Soussan of the Clinique de l'Alma in France and colleagues won the medicine prize this year for discovering how to prevent patients' bowels from exploding during colonoscopies. Yes, every once in a while this routine surgical procedure - in which the bowels are probed by a camera or other device inserted via the anus - goes horribly, explosively wrong. It happens because certain chemicals that are used to clean colons before colonoscopies (in order to clear the way for the camera or other device) can react with bodily fluids to produce a rapid buildup of combustible gases, such as hydrogen and methane. The lasers used by some colonoscopes can then ignite the gases.

Ben Soussan and colleagues figured out which preparatory chemicals pose a danger, and which do not. When asked what a colonic gas explosion is like, Ben Soussan put it this way: "It's big. And loud."

Anatomy

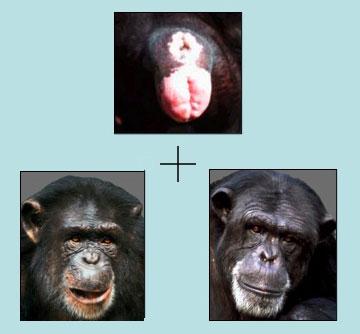

The primatologists Frans de Waal and Jennifer Pokorny of Emory University won this year's Ig Nobel Prize in Anatomy for their discovery that chimpanzees easily recognize their friends' rear ends. Chimps, when given the task of matching the faces and behinds of other chimps, did extremely well when the individuals pictured were ones they lived with. They didn't recognize the behinds of strangers, however - in fact, they even had trouble discerning the strangers' sex.

Humans, meanwhile, can easily identify a person's sex based on facial appearance alone. Whether we can recognize our friends' rear ends "remains to be tested," de Waal said. It could be that humans are extra adept at facial sex recognition for the very reason that we don't often catch a glimpse of each other's private parts. "The chimps, when they look at each other they see the whole body, and it's naked. In humans everything is covered, and so maybe we rely more on faces," he told Life's Little Mysteries.

Physics

Leonardo da Vinci once noted the similarity between flowing hair and flowing water. Turns out, hair is like a fluid. The 2012 Ig Nobel Prize for physics went to a group of researchers in the U.K. for deriving a mathematical equation that describes the fountain-like shape of ponytails.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"In a sense we validated Leonardo's insight," said study co-author Ray Goldstein, a theoretical physicist at the University of Cambridge.

Among the team's findings is that, regardless of a ponytail's length, its "launch angle" the angle at which the outermost hairs emerge from the hair tie is remarkably consistent at 17 degrees from the vertical.

Don't make the mistake of trying to apply the ponytail shape equation to the hair of animals. "This is a case where people are simpler than many animals. A lot of animals have at least two different types of hair in their fur, and understanding that more complex system is another challenge," Ball said. They're taking the research one step at a time.

Psychology

The psychology prize went to Dutch researchers who noticed that leaning to the left makes the Eiffel tower seem smaller. This effect, which they call "posture-modulated estimation," holds only for leftward leans, so it isn't a balance or inner-ear issue. The psychologists believe the effect has to do with the number line. Because people conceive of smaller numbers as being on the left, we subconsciously associate left with other types of smallness, too.

Chemistry

Swedish environmental engineer Johan Pettersson won the chemistry prize for solving the mystery of why people's hair kept turning green in the village of Anderslov, Sweden. It turned out that the hot water they were showering in must have been peeling copper from the pipes and water heaters in their new homes. The copper tinted their hair green, but Pettersson's real concern was whether the water also contained more dangerous metals, such as arsenic. Fortunately it did not; green hair was the worst symptom the villagers would experience - and the problem would go away as the pipes aged.

Pettersson, who sported a green beard for the Ig Nobel Prize Ceremony, said the coppery water phenomenon was probably widespread, but its green-tinting effects are only noticeable among a fair-haired population like Sweden's.

Fluid dynamics

As Rouslan Kretchetnikov and his fellow mechanical engineers struggled to carry their coffees down several flights of stairs at a conference last year, they got to talking about coffee's notorious tendency to spill. Back at the University of California, Santa Barbara, Kretchetnikov and a student decided to explain the phenomenon.

Turns out, the human stride has almost exactly the right frequency to drive the natural oscillations of a cupful of coffee. A person walking at a normal pace and using an average-size mug will tend to spill their coffee at some point between their seventh and tenth step.

To prevent spillage, Kretchetnikov says you must walk slowly, and keep your eyes on your cup. He strongly advises against trying to take a sip on the go. With all that sloshing happening, it's nearly impossible to execute a spill-free cup-to-mouth trajectory. "In the language of sciences: it's a difficult control problem," Kretchetnikov told Life's Little Mysteries.

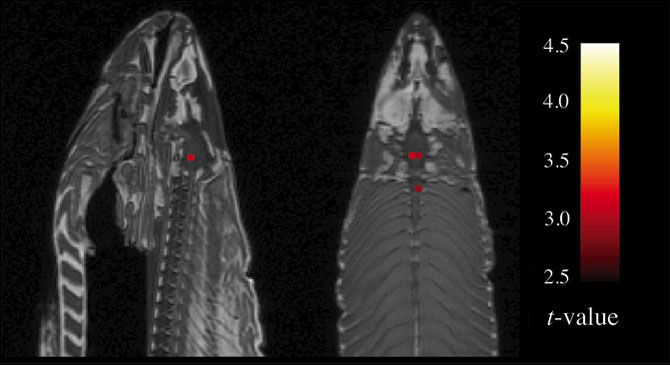

Neuroscience

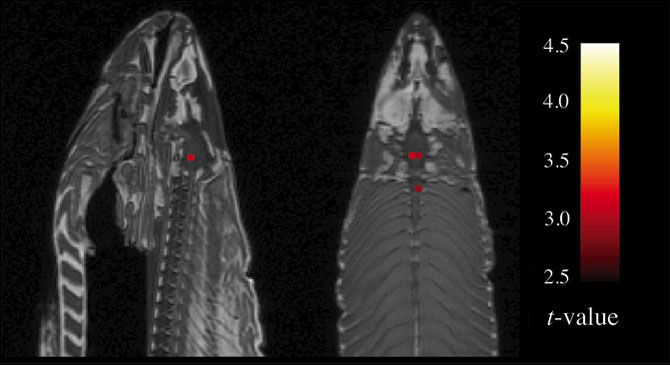

When a group of neuroscientists at Dartmouth did an fMRI scan on the brain of a dead Atlantic salmon they had recently purchased at the supermarket, they were startled to discover that it appeared to be thinking. A pocket of voxels (i.e. 3D or volumetric pixels) in the salmon's brain showed a high level of activity - just what you would expect to see if the neurons in that brain area were firing.

Obviously the dead fish's neurons were doing no such thing. fMRI machines pick up false signals, such as electric fields emanating from light bulbs and magnetic fields generated inside the scanners themselves. That was the point. The neuroscientists normally use fMRI machines to study memory and decision-making in humans rather than braindead fish. They wrote a paper on the fish findings in order to demonstrate the dangers of false positives in fMRI data, and the need to ensure that brain scan data is always statistically significant. For that, they win the Ig Nobel Prize in neuroscience.

Peace

Alchemists never managed to turn iron into gold, but the Russian engineer Igor Petrev wins the Ig Nobel Peace Prize for developing a method for converting surplus TNT and other explosives into diamonds. Ammunition gets overproduced, and the excess must either be detonated or burned. "But you can also use it to make diamonds," Petrev said. He explodes the ammo in "a special chamber" and in "a special way," that produces graphite, metals, gasses and miniscule, 4-nanometer-wide diamonds. These are then extracted from the mix. Just how the separation process works is a secret that, as for now, stays in Russia. But the result is 70 grams of "nanodiamonds" for every kilogram of TNT detonated.

They're not the kind of gems you'd wear on a necklace. According to Petrev, the diminutive carbon crystals instead have many industrial uses, such as surface polishing, modification of galvanic coatings, improvements of oils and, most promising of all, biomedical applications: Nanodiamonds are starting to be used in cancer therapy.

Acoustics

For all those moments when you wish someone would just stop talking, Japanese researchers have invented the SpeechJammer, a device that shuts people up by playing back their voice after a small delay, creating a distracting and unpleasant echo that tends to kill the monologue. Their work has garnered an Ig Nobel Prize in the category of acoustics.

Literature

The U.S. Government General Accountability Office won the literature prize this year for a no-doubt thrilling treatise recommending the preparation of a report to discuss the impact of reports about reports. No word yet on who bought the movie rights.

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science from 2010 to 2012 and is currently a senior physics writer and editor for Quanta Magazine. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with the staff of Quanta, Wolchover won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory writing for her work on the building of the James Webb Space Telescope. Her work has also appeared in the The Best American Science and Nature Writing and The Best Writing on Mathematics, Nature, The New Yorker and Popular Science. She was the 2016 winner of the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award, an annual prize for young science journalists, as well as the winner of the 2017 Science Communication Award for the American Institute of Physics.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus