Complex Geology Behind the Italian Earthquake

Editor's Note: This story was updated at 1:50 p.m. EDT to reflect new estimates of the death toll.

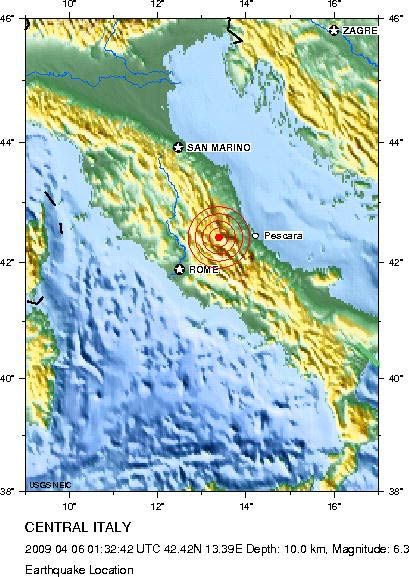

The 6.3 magnitude earthquake that struck central Italy in the wee hours of Monday morning has a complicated geological story behind it.

The epicenter of the quake, which struck at 3:32 a.m. local time (9:30 p.m., April 5 EDT), was near the medieval city of L'Aquila, about 70 miles (110 kilometers) northeast of Rome.

The temblor has killed more than 90 people so far, according to news reports, and left 1,500 injured and thousands homeless. It marks the country's deadliest earthquake in three decades.

[Read: Are Megaearthquakes on the Rise?]

The earthquake was the result of faulting that runs northwest-southeast through the central Apennines, a mountain belt that extends from the Gulf of Taranto in the south to the southern edge of the Po basin in northern Italy.

Several tectonic processes are active in the region: The Adria micro-plate is being subducted under the Apennines from east to west, while at the same time continental collision is occurring between the Eurasia and Africa plates (responsible for the building of the Alps).

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"This is a really complex region," said Stuart Sipkin, a seismologist with the United States Geological Survey (USGS).

This isn't the first major earthquake the region has seen in recent years; in 1997, a 6.0 magnitude quake struck about 53 miles (85 km) north-northwest of the L'Aquila event, killing 11, injuring more 100 and destroying about 80,000 homes in the Marche and Umbria regions, according to the USGS.

[New Related: Seismologists Tried for Manslaughter for Not Predicting Earthquake]

A couple of earthquakes came about three and five hours before today's Italian temblor — such foreshocks are not particularly unusual.

"We certainly see foreshocks," Sipkin told LiveScience. "It's not real common, but it's not uncommon either."

But while they've been observed before, they're "not a good indicator that a big earthquake is coming," Sipkin said. There has been only one documented instance where they were used to successfully predict a major earthquake — in China in the 1970s — and that was a circumstance where foreshocks were steadily increasing in severity and frequency.

The foreshocks in the L'Aquila quake didn't look any different than the "background seismicity" of the region, Sipkin said.

Sipkin said that it's likely that the most damaged buildings were the older ones, but added that how much damage a quake does can depend on how close it occurs to where people live.

A wall of the 13th-century Santa Maria di Collemaggio church collapsed and the bell tower of the Renaissance San Bernadino church also fell in the city's historic center, according to the Associated Press.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.