The 10 Weirdest Things Created By 3D Printing

Odd Printouts

The cost of 3D printing has long kept the technology in a select few hands, but all that is changing as 3D printing blossoms into a full-fledged trend.

This June, Staples will start retailing a consumer 3D printer, the Cube 3D Printer, for $1,299 — not cheap, but not out of reach of the dedicated techie, either. Proponents hope that as costs come down, more sophisticated printers will reach the general public, allowing for digital DIY manufacturing.

Though copyright and quality issues remain a concern, 3D printing has already made its mark in some pretty weird ways. Read on for 10 strange objects created by 3D printers.

A working gun

It looks more like a toy than a deadly weapon, but the world's first 3D-printed gun has gun control advocates as well as pro-gun rights enthusiasts concerned and excited. Last year, Cody Wilson, a radical libertarian/anarchist from the University of Texas' law school, announced plans for printing a gun, establishing a nonprofit called Defense Distributed to fabricate the weapon and distribute the plans.

In early March, Wilson and his team achieved their dream, successfully testing the "Liberator" on a Texas firing range. Except for a firing pin made from a metal nail, the gun is made from plastic pieces printed on an $8,000 Stratasys Dimension SST 3D printer. The gun successfully shot a .380 caliber bullet, but exploded when its creators tried to modify it to shoot a larger 5.7x28 rifle cartridge.

A make-it-yourself violin

The world's first 3D-printed violin is half technological wonder, half papier-mâché project. DIY violin-maker Alex Davies used 3D printing to make a plastic form for the violin's body, which he and his team then covered in newspaper and glue. A piece of cardboard made the neck and some picture-hanging wire served for strings. The result, announced online Feb. 27 via a somewhat-difficult-to-listen-to YouTube video, was no Stradivarius, but its creators declared it "not bad for a weekend and 12 dollars."

Human stem cells

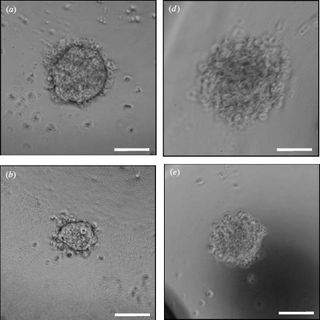

Don't expect to see this in Staples anytime soon, but scientists have developed a 3D printer for stem cells. [7 Cool Medical Uses for 3D Printing]

The device works by creating uniform droplets of living embryonic stem cells, which are the cells present in early development that are capable of differentiating into any type of tissue. The printer is so gentle that it can squirt out as few as five cells at a time without damaging them. Researchers can use the dabs of cells to rapidly test drugs or to build miniature scraps of tissue. The eventual goal is to grow whole organs from scratch.

Dead king's face

After discovering the skeleton of long-lost King Richard III under a parking lot in Leicester, England, archaeologists turned over the skull measurements to facial reconstruction expert Caroline Wilkinson of the University of Dundee. Wilkinson and her colleagues sculpted computerized flesh to computerized bone and then 3D printed the resulting bust — a lifelike look at a man dead more than 500 years.

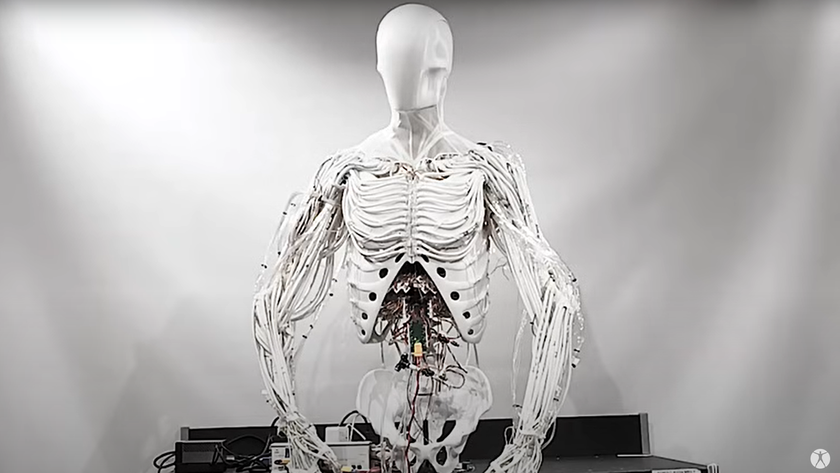

Most of a skull

3D-printed organs may be a dream for the future, but scientists can already build some body parts. In March, surgeons replaced 75 percent of a man's skull with a plastic one made by 3D printing.

Replacing damaged or diseased bone is not new, but the OsteoFab implant is the first to be custom manufactured via 3D printing — an advance that helps bring down the cost. Oxford Performance Materials, the company that created the implant, plans to work on other biocompatible implants for the rest of the body.

Bionic ear

Did you hear that? Probably, if you're wearing a 3D-printed ear created by Princeton University researchers. The bionic ear, made from calf cells, a polymer gel and silver nanoparticles, can pick up radio signals beyond the range of human hearing.

To make the ear, the researchers printed the gel into an approximate ear shape and cultured the calf cells on that matrix to create something appropriately biological. An infusion of silver nanoparticles creates an "antenna" for picking up those radio signals, which could then be transferred to the cochlea, the part of the ear that translates sound into brain signals. However, the researchers have no plans to stick the ear to a human head. Yet.

Your very own fetus

Can't wait to see what your baby will look like? Japanese company Fasotec has you covered. The engineering firm can take magnetic resonance images (MRI) of a developing fetus in the womb and convert them into a 3D-printed paperweight of your fetus in white plastic, surrounded by a clear plastic tummy.

Fasotec's main gig is creating 3D prints of scanned organs for doctors and medical students, so fetus keepsakes are something of a promotional sideline. Japanese moms can get theirs for about 100,000 yen (approximately $975), not including the cost of the MRI.

Springy bikini

It's a technological fashion trend: The world's first ready-to-wear 3D-printed bikini. Sold by Continuum Fashion, the bikini is made of 3D-printed circular plates of nylon connected by thin springs. Because every bikini is made to order, buyers have to order piece-by-piece — a not inexpensive option, given that a single bikini cup starts at $88.

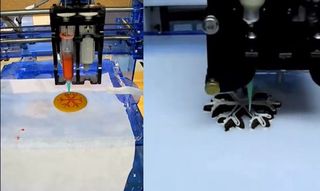

Printed food

Yum. … The fun thing about 3D printers is that they don't have to build their creations with plastic. The Sugar Lab, based in Los Angeles, uses sugar to create delicate and delicious 3D printed cake-toppers. At Cornell University, researchers are experimenting with creating shaped candies and 3D-printed cakes embedded with secret messages in different-colored batter. They even made an octopus out of corn dough.

Egyptian hairstyles

Ancient Egyptian women were often mummified wearing elaborate braids. The magic of 3D printing has brought those hairstyles back to life. In January 2013, researchers at McGill University's Redpath Museum revealed detailed facial reconstructions created with a combination of computed tomography (CT) scanning and 3D printing. One 20-year-old woman wore her hair pulled back in multiple plaits wound into a chignon at the crown of her head. What the 3D printed reconstruction can't explain is why the woman had three wounds to her side — or whether those punctures caused her death.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.