Facts About Zirconium

Zirconium is a silver-gray transition metal, a type of element that is malleable and ductile and easily forms stable compounds. It is also highly resistant to corrosion. Zirconium and its alloys have been used for centuries in a wide variety of ways.

It is commonly used in corrosive environments. Zirconium alloys can be found in pipes, fittings and heat exchangers, according to Chemicool. Zirconium is also used in steel alloys, colored glazes, bricks, ceramics, abrasives, flashbulbs, lamp filaments, artificial gemstones and some deodorants, according to Minerals Education Coalition.

Other uses for zirconium include catalytic converters, furnace bricks, lab crucibles, surgical instruments, television glass, removing residual gases from vacuum tubes, and as a hardening agent in alloys such as steel, according to Lenntech. Also, zirconium carbonate is used to treat poison ivy, according to the Jefferson Laboratory.

Zirconium has been found in S-type stars, the sun, meteorites and in lunar rocks, according to the Los Alamos National Laboratory. Lunar rocks appear to have a surprisingly high zircon content compared to terrestrial rocks, according to analysis of lunar rock samples from the various Apollo missions.

On Earth, sources for zirconium are primarily the minerals zircon and baddeleyite (zirconium dioxide), which are mined in the United States, Australia, Brazil, South Africa, Russia, and Sri Lanka, according to Minerals Education Coalition. Zirconium's natural abundance in Earth's crust is 165 parts per million by weight, according to Chemicool.

Just the facts

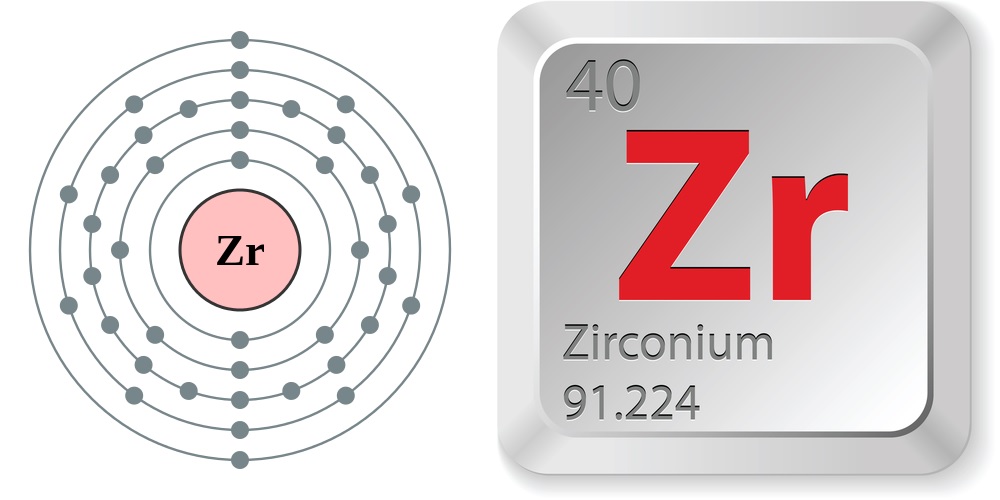

- Atomic number (number of protons in the nucleus): 40

- Atomic symbol (on the periodic table of elements): Zr

- Atomic weight (average mass of the atom): 91.22

- Density: 3.77 ounces per cubic inch (6.52 grams per cubic cm)

- Phase at room temperature: Solid

- Melting point: 3,362 degrees Fahrenheit (1,850 degrees Celsius)

- Boiling point: 7,952 F (4,400 C)

- Number of natural isotopes (atoms of the same element with a different number of neutrons): 5. There are also 20 artificial isotopes created in a lab.

- Most common isotopes: Zr-90 (51.5 percent of natural abundance), Zr-94 (17.38 percent of natural abundance), Zr-92 (17.15 percent of natural abundance), Zr-91 (11.2 percent of natural abundance), Zr-96 (2.8 percent of natural abundance)

History

Zircon, a gemstone, comes in blue, yellow, green, brown, orange, red and occasionally purple varieties. The word comes from the Persian "zargun" or gold color. It has been used in jewelry and other decoration for centuries, according to Peter van der Krogt, a Dutch historian. It comes closer to resembling a diamond than any other natural gem, according to Minerals.net. During the Middle Ages, zircon was even believed to induce sleep, promote wealth, honor and wisdom, and to drive away plagues and evil spirits.

Martin Heinrich Klaproth, a German chemist, discovered zirconium in 1789 in a sample of zircon from Sri Lanka, according to Chemicool. The sample's composition was found to be 25 percent silica, 0.5 percent iron oxide, and 70 percent a new oxide that he named zirconerde (or "zircon of the earth"). Klaproth also later found zirconerde in jacinth, a pale yellow variety of zircon, but he was unable to separate the metal, according to van der Krogt.

Sir Humphry Davy, an English chemist, attempted to separate zirconerde to get pure zirconium in 1808 using electrolysis, but was unsuccessful, according to Chemicool. He did, however, suggest the name of zirconium for the metal itself, according to van der Krogt.

Jons J. Berzelius, a Swedish chemist, isolated zirconium in 1824, according to Chemicool. He produced zirconium as a black powder as a result of heating an iron tube containing a mixture of potassium and potassium zirconium fluoride (Kr2ZrF6).

Anton Eduard van Arkel and Jan Hendrik de Boer, Dutch chemists, produced pure zirconium in 1925 by heating zirconium tetrachloride (ZrCl4) with magnesium, according to the Royal Society of Chemistry. This method produced a pure zirconium crystal bar, according to Chemicool.

Who knew?

- Zircon is sometimes confused with cubic zirconia, a synthetic, inexpensive diamond simulant. However, according to Minerals.net, the two are entirely separate substances, and have no connection with each other except that they both contain the element zirconium in their chemical structure.

- According to Lenntech, approximately 7000 tons of zirconium metal is produced annually.

- Zirconium combines with silicate to create the natural semiprecious gemstone zircon, according to Chemicool. Zirconium combined with dioxide creates cubic zirconia, which is commonly used as a substitute for diamonds.

- Zirconium has very low toxicity and it is estimated that humans ingest about 50 micrograms (1.8 x 10-6 ounces) per day, most of which passes through the digestive system without being absorbed, according to Lenntech.

- The human body is made of approximately 0.000001 percent zirconium, according to Minerals Education Coalition.

- The use of lithium zirconate may be useful in absorbing excess carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, according to Chemicool.

- Rocks containing zircon that were found in Australia in 2000 were dated to be 4.4 billion years old and the oxygen isotope ratio (O16/O18) showed that life began on Earth nearly 500 million years earlier than previously believed, according to an article written by John Emsley, a science writer, published in Nature in 2014.

- Zirconium powder can spontaneously ignite in air, according to Chemicool. Because of this property, powdered zirconium is sometimes used in explosive devices, according to Emsley.

- According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, zirconium powder can cause eye irritation for short-term exposure and can be harmful to the lungs for long-term or repeated exposure.

Current research

Because if its high tolerance to corrosion and its strength, zirconium is present in several compounds in various medical uses. According to Zirconia Concept, the use of zirconium compounds in medicine began in 1969 when it was used to manufacture hip prosthetics. Zirconia (ZrO2) prosthetics were developed as an alternative to titanium, steel and aluminum and were shown to be both more resilient and with better biocompatibility. Approximately 300,000 patients over the past four decades with zirconia prosthetics have shown no negative responses.

Zirconia is also widely used in dental restorations, according to Zirconia Concept, and is typically stabilized with yttria (ZrO2Y2O3). The yttria-zirconia compound has many benefits over other materials. It is more compatible with the human body and has twice the flexural strength and four times the compression resistance of steel. It also has greater resistance to acids bases found in many foods.

Other new ideas for using zirconium alloys in the medical field include a patent filed in 1999 by James Davidson and Lee Tuneberg, American inventors. They describe an alloy containing niobium, titanium, zirconium and molybdenum (NbTiZrMo) and its benefits for dental and other medical devices. The zirconium in the alloy gives higher mechanical properties as well as reduces the melting temperature (along with titanium), further stabilization, and improved corrosion resistance.

Another patent filed by Shuichi Miyazaki, Heeyoung Kim and Yosuke Sato, Japanese scientists, in 2012 describes a zirconium alloy that has super elastic properties that can be used in biological and medical fields. Zirconium is alloyed with titanium, niobium and either tin or aluminum, or both. The alloy is similar to the elasticity of human bones, according to values given by Young's modulus, making it an ideal material for uses inside the human body including artificial bones, joints, and teeth as well as orthodontic wires, stents, bone plates, and other medical implants.

Even though zirconium and other elements in alloys for dental and medical uses are nontoxic, there are still ongoing studies to ensure that the materials themselves don't have adverse side affects over the long term. One such study by a group of scientists in Italy, published in PLOS One in 2016, on a group of obese participants found that there might be a link between zirconium implants and some health problems, such as inflammation and skeletal and connective tissue disorders. The amount of change in certain biological markers (miRNAs) was very small and it is believed that they accumulate over time, which can make it difficult to pin point the exact cause. While additional research is needed, the study helped in the understanding the link between the human body and implanted medical devices. The goal, according to the authors, is to take advantage of mrRNAs to assist in wound healing and host-implant integration.

Additional resources

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Rachel Ross is a science writer and editor focusing on astronomy, Earth science, physical science and math. She holds a Bachelor of Arts in Philosophy from the University of California Davis and a Master's degree in astronomy from James Cook University. She also has a certificate in science writing from Stanford University. Prior to becoming a science writer, Rachel worked at the Las Cumbres Observatory in California, where she specialized in education and outreach, supplemented with science research and telescope operations. While studying for her undergraduate degree, Rachel also taught an introduction to astronomy lab and worked with a research astronomer.