Baby's Life Saved with 3D Printing

When April and Bryan Gionfriddo brought home their newborn son, Kaiba, in October 2011, he seemed like a healthy baby. But one night, when the family was out to dinner, Kaiba stopped being able to breathe and turned blue. Bryan laid Kaiba, just 6 weeks old, on the restaurant table and performed chest compressions on him before he was rushed to the hospital.

After 10 days, Kaiba was sent home, but he turned blue again two days later. That's when doctors realized Kaiba had a rare condition called tracheobronchomalacia, in which the windpipe is so weak that it collapses, preventing air from flowing to the lungs.

Kaiba's case was severe, and his heart would stop beating on a daily basis, April Gionfriddo said. Even after surgeons placed a tube in their child's trachea to help him breathe, and put him on a ventilator, the life-threatening problems continued.

"We were scared," Gionfriddo said. "We didn’t think he was going to leave the hospital."

But researchers at the University of Michigan had been working on a solution to this very problem. They had developed a way to use new technology called 3D printing to create a splint that would fit precisely around Kaiba's airway, holding it open and making it possible for him to breathe. Three-dimensional printers "print" an object by building it in very thin slices, one layer at a time. [Video: How Doctors Made Kaiba's Splint]

"As soon as the splint was put in, the lungs started going up and down for the first time, and we knew he was going to be OK," said Dr. Glenn Green, an associate professor of pediatric otolaryngology at the university.

Traditionally, airway splints have been carved by hand, but this takes a long time, and the splints do not exactly match a patient's airway.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"I'd like to think I'm a pretty good artist, but I can't even come close to matching a picture," Green said.

Kaiba's case is the first time 3D printing has been used to create a medical device that saved someone's life, the researchers said.

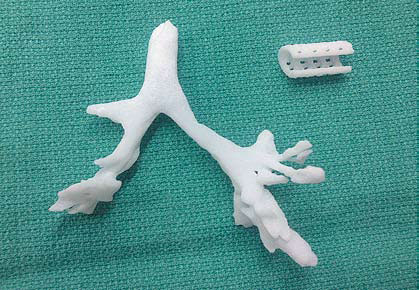

3D-printed splint

For years, Green wanted better treatments for patients with severetracheobronchomalacia. Recently, the researchers began work on a 3D-printed splint and had planned to test it in a clinical trial. But when they heard of Kaiba's case, they realized the technology could save the baby's life, and Kaiba became the first patient treated using the procedure. The device received emergency clearance from the Food and Drug Administration.

To construct the splint, doctors made a precise image of Kaiba's trachea and bronchus with a CT scan. Then, using computer modeling, they created a splint that would exactly fit around the airway, said study researcher Scott Hollister, a professor of biomedical engineering at the university. The model was then produced on a 3D printer.

The device is made out of a material called polycaprolactone, and will dissolve after about three years. By that time, Kaiba's windpipe will have grown, reducing pressure on the organ, and the splint will no longer be needed.

A splint like Kaiba's splint can be made in about 24 hours and costs about one-third the price of a hand-carved version, Green said.

Hollister and colleagues are also working to make 3D-printed devices that will aid in ear, nose and bone reconstruction. For these devices, the 3D printer would construct a scaffold that could be seeded with stem cells from fat or bone. These would then grow into tissue around the scaffold. The researchers have tested these devices in animal models.

Earlier this year, researchers at Weill Cornell Medical College reported that they had made a synthetic ear using a 3D printer.

'Doing wonderful'

Gionfriddo said she had doubts about using an untested device in her son, but she and her husband were desperate for solutions. "At that point, we would just take anything and hope it would work," she said.

Twenty-one days after the procedure, Kaiba no longer needed a ventilator to help him breathe. In total, he spent four months in the hospital.

Now at 20 months old, Kaiba is doing "wonderful," said Gionfriddo, who lives in Youngstown, Ohio. "We are so thankful that something could be done for him. It means the world to us."

Kaiba's doctors describe his case in the May 23 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow MyHealthNewsDaily @MyHealth_MHND, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on LiveScience.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.