Epilepsy: Causes, symptoms & treatments

There are many different kinds of epilepsy with symptoms ranging from mild to potentially life-threatening.

Epilepsy is a chronic condition characterized by recurrent seizures that can range from brief lapses of attention or muscle jerks to severe and prolonged convulsions. More than 50 million people worldwide have epilepsy, and 80% of those people live in developing regions, according to the World Health Organization (WHO)The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that 3.4 million people in the United States have active epilepsy. While symptoms of epilepsy may vary among cases, the disorder always causes seizures, which are periods of sudden irregular electrical activity in the brain that can affect a person's behavior.

Epilepsy seizures, symptoms and causes

Epilepsy is classified into four categories, said Dr. Jacqueline French, a neurologist who specializes in treating epilepsy at NYU Langone Health. Idiopathic epilepsy (also called primary or intrinsic epilepsy) is not associated with other neurologic disease, and has no known cause except possibly a genetic one. Acquired (or secondary) epilepsy can arise from prenatal complications, traumatic brain injury, stroke, tumor and cerebrovascular diseases.

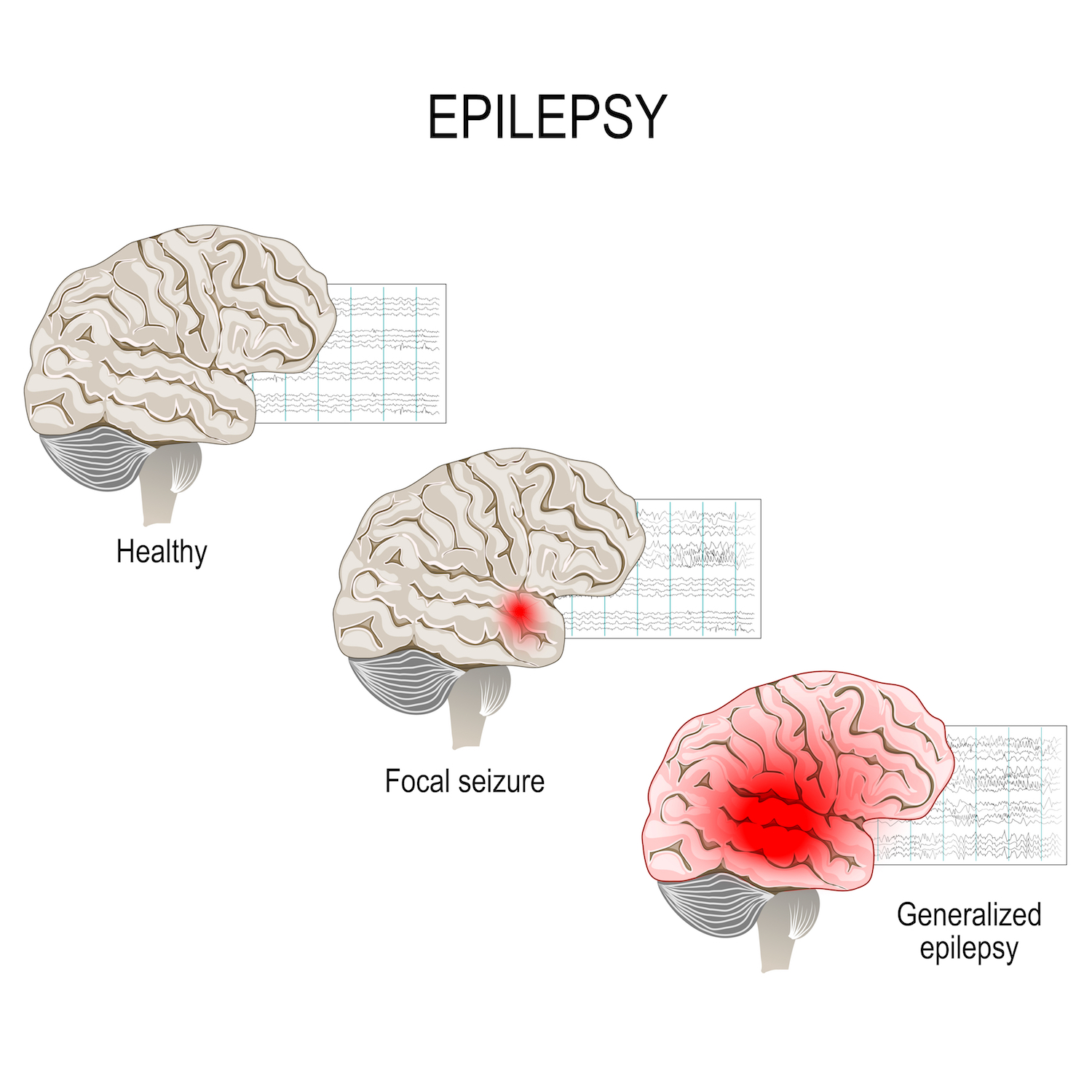

Within each of these two categories, there is generalized, or mixed epilepsy, which involves electrical instabilities in many areas of the brain; and focal epilepsy, in which the instability is confined to one area of the brain.

Different kinds of seizures are common to each category of epilepsy, according to the CDC. Generalized seizures vary in severity: Absence seizures may cause a person to stare off into space or blink rapidly, while tonic-clonic seizures cause muscle jerks and loss of consciousness. Focal seizures, on the other hand, might cause a person to experience a strange taste or smell, or act dazed and unable to respond to questions.

In each case, epileptic symptoms occur because normal signaling between neurons (nerve cells in the brain) has been disrupted. This may be due to abnormalities in brain wiring, an imbalance of nerve-signaling chemicals called neurotransmitters or a combination of the two. The temporal lobe of the brain is known to function differently in people with epilepsy compared to healthy individuals, suggesting it plays a role in the condition, said Dr. Brian Dlouhy, a neurosurgeon and researcher at the University of Iowa.

Epilepsy may develop at any point during a person's life, and sometimes it may take years after a brain injury for signs of epilepsy to show, French said.

"There's an enormous focus from [the National Institutes of Health] and others to find a way to intervene" before the condition sets in, she said, but currently, there is no way to fully prevent or cure the condition.

While the predominant symptoms of epilepsy are seizures, having a seizure doesn't always mean that a person has epilepsy. Seizures can also be a result of head injuries due to falls or other trauma, but epileptic seizures are strictly caused by irregular electrical activity in the brain.

Spontaneous, temporary symptoms such as confusion, muscle jerks, staring spells, loss of awareness and disturbances in mood and mental functions can occur during seizures.

How is epilepsy diagnosed?

Clinicians can measure and identify abnormal electrical activity in the brain with electroencephalography (EEG). People with epilepsy often display abnormal patterns of brain waves even when they are not experiencing a seizure. Therefore, routine or prolonged EEG monitoring can diagnose epilepsy, according to Johns Hopkins Medicine.

EEG monitoring, in conjunction with video surveillance over periods of wakefulness and sleep, can also help rule out other disorders such as narcolepsy, which may have similar symptoms as epilepsy. Brain imaging such as PET, MRI, SPECT and CT scans observe the structure of the brain and map out damaged areas or abnormalities, such as tumors and cysts, which can be the underlying origins of seizures, according to the Mayo Clinic.

Epilepsy treatment and medication

People with epilepsy may be treated by medication, surgery, therapies or a combination of the three. The WHO estimates that overall, 70% of people with epilepsy could control their seizures with anti-epileptic medication or surgery, but 75% of people with epilepsy who live in developing regions do not receive treatment for their condition. This is due to a lack of trained caregivers, inability to access medication, societal stigma, poverty and deprioritization of epilepsy treatment.

The 30% of cases that cannot be completely managed with medication or surgery falls under the category of intractable or drug-resistant epilepsy. Many drug-resistant forms of epilepsy occur in children, French said.

Medication

Anticonvulsant drugs are the most commonly prescribed treatment for epilepsy, according to French. There are more than 20 epileptic drugs available on the market, including carbamazepine (also known as Carbatrol, Equetro, Tegretol), gabapentin (Neurontin), levetiracetam (Keppra), lamotrigine (Lamictal), oxcarbazepine (Trileptal), oxcarbazepine (Trileptal), pregabalin (Lyrica), tiagabine (Gabitril), topiramate (Topamax), valproate (Depakote, Depakene) and more, according to the Epilepsy Foundation.

Most side effects of anticonvulsants are relatively minor, including fatigue, dizziness, difficulty thinking or mood problems, French said. In rare cases, the drugs can cause allergic reactions, liver problems and pancreatitis.

Starting in 2008, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) mandated all epilepsy medications to bear a label warning of the increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors. A 2010 study following 297,620 new patients treated with an anticonvulsant found that certain drugs, including gabapentin, lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine and tiagabine, were associated with a higher risk of suicidal acts or violent deaths.

Surgery

Surgery may be a treatment option if a patient experiences a certain category of epilepsy, such as focal seizures, where seizures begin in a small, well-defined spot in the brain before spreading to the rest of the brain, according to the Mayo Clinic. In these cases, surgery can help relieve the symptoms by removing the parts of the brain that cause seizures. However, surgeons will avoid operating in areas of the brain that are necessary for vital functions such as speech, language, vision or hearing.

Other therapies

Four other therapies may help patients reduce the number of seizures they have. Deep brain stimulation, approved as a treatment for epilepsy in 2018 by the FDA, sends constant shocks to an electrode implanted in the part of the brain called the thalamus.

A related therapy, called responsive neurostimulation (RNS), was approved by the FDA in 2013. It analyzes brain activity and provides targeted stimulation to specific brain areas to stop the progression of seizures as they arise.

Vagus nerve stimulation, in which a pacemaker-like device is inserted in the chest and sends bursts of electricity through the vagus nerve to the brain, can sometimes reduce seizures in cases of intractable epilepsy, although there is weak evidence that the therapy is associated with reduced seizure frequency over time, according to the American Academy of Neurology.

Finally, studies have found that adopting a ketogenic diet, which is low in carbs and high in fat, may reduce seizures for people with intractable epilepsy.

What is SUDEP?

A rare but serious complication of epilepsy is SUDEP, or sudden unexpected death in epilepsy. SUDEP affects 1 in 4,500 children with epilepsy and 1 in 1,000 adults with epilepsy each year, according to the American Academy of Neurology. Dlouhy, who specializes in SUDEP, says most people who experience the complication are found facedown in their beds, having apparently suffocated during a seizure.

The mechanism for SUDEP isn't fully understood, though Dlouhy's research has shown that stimulating the amygdala, a region of the brain within the temporal lobe, causes mice to stop breathing. While not tested conclusively in humans, this finding suggests that a seizure could cause SUDEP by inhibiting the impulse to breathe.

Patients with childhood-onset intractable epilepsy who experience tonic-clonic seizures are at the highest risk of SUDEP, according to Dlouhy. The complication is much more common than researchers previously realized, he said. The risk of SUDEP can be lowered by controlling seizures, putting monitors in the bedroom to alert parents or caregivers of a nighttime seizure or buying special bedding or breathable pillowcases. However, there is no way to completely eradicate the risk of SUDEP, Dlouhy said.

Coping and management

Epilepsy patients may need to adjust certain elements of their lifestyle, such as recreational activities, education, occupation or transportation, in order to accommodate the unpredictable nature of their seizures, according to the Mayo Clinic.

Epilepsy can be life-threatening, French said. Beside SUDEP, a person experiencing a seizure could fall down and hit their head, or be submerged while swimming — people with epilepsy are 15 to 19 times more likely to drown than nonepileptic individuals, according to the Mayo Clinic. People with epilepsy may also be at a higher risk of suicide due to associated mood disorders or as a side effect of their medication, French said.

Intractable epilepsy from a young age can cause a child to fall behind in development, since seizures can cause them to miss school, impairing their learning and IQ, Dlouhy said.

Nonetheless, many epilepsy patients can still lead healthy and socially active lives, especially after educating themselves and the people around them about the facts, misconceptions and stigma surrounding the disease.

What to do if you see someone experiencing a seizure

When somebody is having a seizure with convulsions, gently roll the person to his or her side to ease breathing and put something soft and flat under the person's head to prevent head trauma. Do not put anything into the person's mouth since it could injure their teeth or tongue, and try to move sharp objects away from the area rather than restricting the person's motion, the CDC advises. Help loosen any tight collars or neckties if necessary.

It's also important to record the duration and the symptoms of the seizure so the patient can provide those details to their doctor at a future appointment. The CDC recommends calling 911 for a seizure lasting longer than five minutes.

Additional resources

Learn more about living with epilepsy at the Epilepsy Foundation. Read about epilepsy diagnosis and treatment at the American Association of Neurological Surgeons. Check out useful facts and figures about the disorder from the World Health Organization.

Bibliography

American Academy of Neurology. (2017). Practice Guideline: Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy Incidence Rates and Risk Factors. https://www.aan.com/Guidelines/home/GetGuidelineContent/852

Britton, J.W., et al. (2021, September 28). Antiepileptic drugs and suicidality. Drug, Healthcare and Patient Safety. 2010; 2: 181–189. doi: 10.2147/DHPS.S13225

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, September 30). Epilepsy Fast Facts. https://www.cdc.gov/epilepsy/about/fast-facts.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, September 30). Epilepsy: Types of Seizures. https://www.cdc.gov/epilepsy/about/types-of-seizures.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, January 2). Epilepsy: Seizure First Aid. https://www.cdc.gov/epilepsy/about/first-aid.htm

Dlouhy, B.J., et al. (2015, June 2). Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy: basic mechanisms and clinical implications for prevention. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2016; 87: 402-413. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2013-307442

Epilepsy Foundation. (n.d.). Seizure Medication List. Retrieved May 2, 2022 from https://www.epilepsy.com/tools-resources/seizure-medication-list

Hitti, M. (2008, December 16). Epilepsy Drugs Get Suicide Risk Warning. WebMd. https://www.webmd.com/epilepsy/news/20081216/epilepsy-drugs-get-suicide-risk-warning

Johns Hopkins Medicine. (n.d.). Diagnosing Seizures and Epilepsy. Retrieved May 2, 2022 from https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/epilepsy/diagnosing-seizures-and-epilepsy

Mayo Clinic. (2021, October 7). Epilepsy: Diagnosis & treatment. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/epilepsy/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20350098

Mayo Clinic. (2021, October 7). Epilepsy: Symptoms & causes. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/epilepsy/symptoms-causes/syc-20350093

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (2022, April 13). Brain stimulation therapies for epilepsy. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/about-ninds/impact/ninds-contributions-approved-therapies/brain-stimulation-therapies-epilepsy

World Health Organization. (2022, February 9). Epilepsy. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/epilepsy

This article is for informational purposes only, and is not meant to offer medical advice. This article was last updated on May 2, 2022. It was previously updated on Aug. 14, 2019, by Live Science contributor Maddie Bender.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.