Spanish Empire Bead Cache Found Off Georgia

A cache of some 70,000 glass beads from all over the world has been unearthed at an island off Georgia, comprising the largest repository ever from what was one of the Spanish empire's most remote and wealthy outposts, and revealing more about 17th-century trade routes.

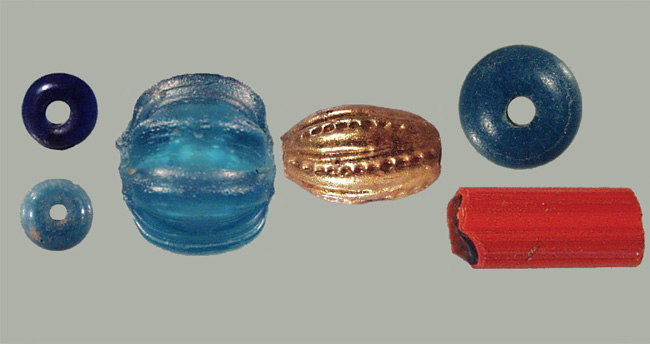

Made of French and Chinese blue glass, Dutch layered glass and Baltic amber, the beads were found as part of an ongoing research project at the former Mission Santa Catalina de Guale on what is now called St. Catherines Island. Founded in the 16th century, this site was the capital and administrative center of the province of Guale in Spanish Florida for the better part of a century. "This is the northernmost outpost of the Spanish empire, but we see evidence of ancient trade routes from China via Manila's galleons to Mexico and Spain," said Lorann Pendleton, director of the archaeology laboratory at the American Museum of Natural History Museum in New York. A team from the museum led the excavation. "We also have found perhaps the first evidence of Spanish beadmaking, along with beads from the main centers of Italy, France, and the Netherlands." The mission of Santa Catalina de Guale was inhabited by Franciscan missionaries and local people for most of the 17th century. The mission was a major source of grain for Spanish Florida and a provincial capital until 1680, when the mission was abandoned after a British attack. Since 1974, David Hurst Thomas, curator of anthropology at the museum, and colleagues have been unearthing this part of the island's history. Beads found in cemetery The current research is based on the complete excavation of the church's cemetery and extensive survey and excavation in other parts of the mission. Years of analysis reveal roughly 130 different types of beads on the island. Most of the more common beads are of Venetian and potentially French origin, with new research suggesting that one of the most common beads of the 17th century, the Ichtucknee blue, was manufactured in France. Some of the unique beads, though, may be Spanish, Chinese, Bohemian, Indian or Baltic in origin. While roughly 2,000 beads were found elsewhere at the mission (such as in the convent), most were found in the cemetery under the church. These were items intentionally deposited with individuals as grave goods. Most burials found with large numbers of beads appear to date to the earlier part of the mission's history (the first half of the 17th century); items found with burials that date to the latter half of the 17th century are more likely to be religious medallions and rosaries. But because almost half the beads in the cemetery were buried with a few individuals who tended to be near the altar, it is often assumed that they were of high status in the community. "A higher number of beads were found toward the altar, and some of the highest-status individuals (by number of beads) were children," Pendleton said. "This gives us lots of information about Guale society and means that status was ascribed with birth." Trading corn for beads The number of beads found on St. Catherines Island suggests that Santa Catalina de Guale was a relatively wealthy outpost. The island is fertile and was the capital of a mission province, both potential explanations for the high number of beads found when compared to other missions. "St. Catherines was a frontier mission, but it also was a bread basket for the east-coast Spanish empire," said Pendleton. "The missionaries at St. Augustine were always starving — you can read this in the letters written at the time — because that area was too humid and hot for corn to grow easily. St. Catherines was able to trade corn for beads." The new research, authored by Elliot Blair of the University of California, Berkeley, Pendleton, and bead expert Peter Francis, Jr., was published on April 8 in the journal Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History. Francis, who did much of the detailed analysis of where the beads were manufactured, died while on a research trip to Ghana, Africa, in 2002. The research was funded in part by the Edward John Noble Foundation.

- Quiz: The Artifact Wars

- Top 10 Weird Ways We Deal with the Dead

- Anthropology: News and Information

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.