Achilles' Heel of Flu Virus Revealed, Brings Hope for New Drugs

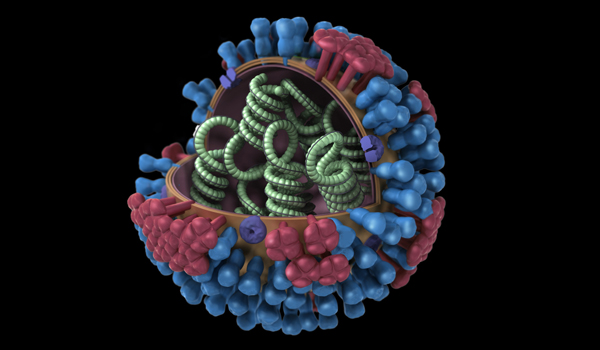

New images of the influenza A virus, whose strains cause the seasonal flu and the H1N1 "swine" flu, have revealed its Achilles' heel, researchers say, and the finding could lead to a targeted drug that can fight all strains of the virus.

The weakness stems from a basic structure in all flu viruses, called the M2 channel, which is key in helping the virus reproduce.

About four years ago, a tiny change occurred in this channel, the researchers said, making flu drugs such as amantadine and rimantadine ineffective. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention stopped recommending using the drugs to fight the flu.

"We think we can pin down the types of changes that could occur, and find drugs for all" strains of flu , said study researcher David Busath, a biophysicist at Brigham Young University in Utah.

The finding helps researchers understand why the virus isn't susceptible to the old influenza drugs anymore, Busath said.

With a drug developed to target this particular channel, "you could be safe tomorrow," Busath said.

The flu virus is mutating and changing all the time, which is why there must be a new flu vaccine every year to accommodate the new mutations, he said. But every flu virus has an M2 channel, and it must work properly for the virus to infect a host.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It turns out there's only a small handful of changes, in the heart of the channel, that still allow the virus to work well," Busath said. "And if it can't work, the virus can't reproduce. And we know all of the possible changes that allow it to work."

Previous images of influenza A didn't reveal the changes in the M2 channel, making it hard for scientists to develop a drug that could effectively target the structure.

Because the structures of the virus are so tiny, Busath and researchers from Florida State University used a technique called solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance which is similar to an MRI, but used on atoms and molecules to get a refined view of the flu's structure.

"We have some new theories to test for possible compounds that would work on the M2 [channel], and we're excited to try them out," Busath told MyHealthNewsDaily.

The imaging technique the researchers used could also be used to provide images of the proteins in plasma membranes in the nervous system, he said.

The study was published today (Oct. 21) in the journal Science.

Measles has long-term health consequences for kids. Vaccines can prevent all of them.

100% fatal brain disease strikes 3 people in Oregon