The Worms Crawl in, the Worms Treat Colitis

Faced with removal of his colon when treatments for his ulcerative colitis were unsuccessful, a 36-year-old California man opted for an unconventional treatment. He traveled to Thailand and, after consultation with a parasitologist there, swallowed 1,500 parasitic worm eggs.

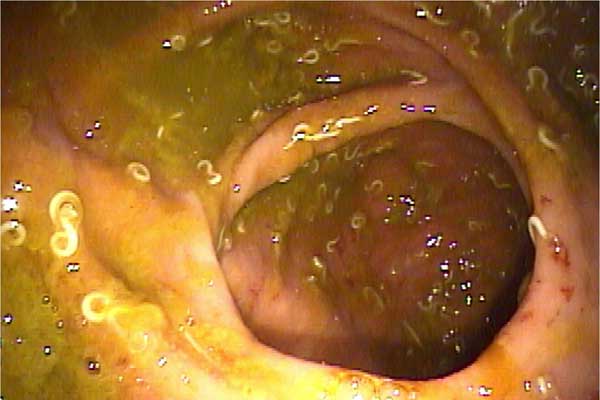

In a study of the patient's case published today (Dec. 1), researchers showed how these wriggling, symbiotic friends may have helped alleviate the symptoms of the anonymous man's inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in the years since then. Within a year of downing the worms, his colitis had improved to the point where he no longer needed treatment.

The case report is one of several lines of research into the role of parasitic worms, known as helminthes, in altering immune-system responses. Because patients with ulcerative colitis suffer when their immune systems trigger inflammation that destroys the lining of their bowels, ways of treating that inflammation are a research target.

"There's been a lot of interest in how helminth exposure affects autoimmunity and inflammatory disorders," said study researcher Mara Broadhurst, a doctoral student in immunology at the University of California, San Francisco.

While the report seemed to suggest a new treatment for a painful and hard-to-treat disease, it also presented some signals for caution.

A hypothesis for this type of research is that the presence of the parasites suppresses the immune system's response, thus reducing the pain brought on by that response. But "that's not actually what we found," Broadhurst said. "We didn't see a generalized suppression of inflammation, but rather a modified response."

She explained that what seemed to happen was the body tried to expel the worms, and in doing so produced mucus. The thick fluid that coated the intestinal walls soothed the symptoms of colitis.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For people with ulcerative colitis, Broadhurst warned that the worm treatment is far from being proven effective or even harmless for everyone.

"I don't think that we're at the stage where we can make this a general recommendation by any means," she said. Because the disease affects patients in different ways, one treatment would not be expected to work in all cases.

"We certainly aren't at the stage where we understand which subsets of patients will benefit," said Broadhurst. "With certain conditions, with particular defects ... exposure to helminths can actually exacerbate inflammation."

For this reason, Dr. Peter Hotez, chair of the department of microbiology, immunology and tropical medicine at the George Washington University Medical Center in Washington, D.C., remains skeptical. His research focuses on the burden brought on by helminths and other infections in the developing world, including the trichuriasis worms that were ingested by the unnamed California man.

These worms are "the leading cause of colitis in hundreds of millions of children in developing countries," Hotez said.

"Ulcerative colitis goes through remissions spontaneously on its own, and this could have been the case," Hotez told MyHealthNewsDaily. "Bottom line for me: Teating with worms is not a long-term effective strategy for IBD, and is potentially very dangerous because you are actually causing a serious form of IBD by administering the worms."

But Broadhurst said there was good evidence the patient improved not just during a natural change in the course of his disease. In 2008, four years after his first worm-egg meal, she said, his symptoms returned and the number of worms inside his bowel had declined, so he ate 2,000 more eggs.

"As the worms reached the end of their lifespan, the inflammation came back, and we had the benefit of seeing a second round of the same phenomenon," she said.

Both Broadhurst and Hotez agreed that, ideally, treatment for patients would involve a compound isolated from the worms, rather than worms themselves.

Treatment research could focus on finding and reproducing the signal for cells to release mucus to heal the lining of the bowel.

"That has a lot of promises for developing drugs that use those signaling pathways," said Broadhurst. "Ideally, the introduction of a live parasite wouldn't be necessary for patients who want to pursue this form of treatment."

Flu: Facts about seasonal influenza and bird flu

What is hantavirus? The rare but deadly respiratory illness spread by rodents