Nothing to Sneeze At: Cats Worse Than Dogs for Allergies

If you have pet allergies, chances are it is Fluffy rather than Fido that's making you sneeze. While an estimated 10 percent of people are allergic to household pets, cat allergies are twice as common as dog allergies, according to the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology.

Among children, about one in seven between ages 6 and 19 prove to be allergic to cats.

Contrary to popular belief, it's not cat fur that causes those itchy, watery eyes. Most people with cat allergies react to a protein found on cat skin called Fel d 1.

The reason that cat allergies are more common has to do with the size and shape of the protein molecule, rather than how much dander the animal sheds, according to Mark Larché, an immunology professor at McMaster University in Ontario.

The protein enters the air on bits of cat hair and skin, and it is so small and light — it's about one-tenth the size of a dust allergen — that it can stay airborne for hours. "Dog allergens don't stay airborne the same way cat allergens do. The particle size is just right to breathe deep into your lungs," Larché said.

The Fel d 1 protein is also incredibly sticky, readily glomming onto human skin and clothes and remaining there, making it ubiquitous in the environment. It has been found in places where there are no cats — classrooms, doctors' offices, even the Arctic, Larché said.

While there are no truly hypoallergenic cat breeds — all cats produce the protein, which experts surmise may have something do with pheromone signaling — some cats make more of it than others.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Male cats, especially unneutered males, produce more Fel d 1 than female cats. Testosterone increases glandular secretions," said Dr. Andrew Kim, an allergist at the Allergy and Asthma Centers of Fredricksburg and Fairfax, in Virginia.

If you have cat allergies, there are steps you can take to reduce them. Avoiding contact with cats is one option, though not always a popular choice. Even after a cat is taken out of a house, allergen levels may remain high for up to six months, Kim said.

Limiting a cat's access to the bedrooms of allergic people, using high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters, bathing the cat and removing allergen-trapping carpeting may also help.

For those who can't avoid cat dander, allergy shots may be an option. Small injections of the allergen can help build immune system tolerance over time. "It takes about six months of weekly injections of increasing potency to reach a maintenance level, followed by three to five years of monthly injections, for the therapy to reach full effectiveness," said Dr. Jackie Eghrari-Sabet, an allergist and founder of Family Allergy and Asthma Care in Gaithersburg, Md.

A less burdensome fix for cat allergies may be on the horizon. Phase 3 clinical trials are set to begin this fall for a cat allergy vaccine that Larché helped develop. Early tests have shown the vaccine to be safe and effective without some of the side effects of allergy shots, such as skin reactions and difficulty breathing. Larché receives research funding from pharmaceutical companies Adiga Life Sciences and Circassia.

Follow MyHealthNewsDaily on Twitter @MyHealth_MHND. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

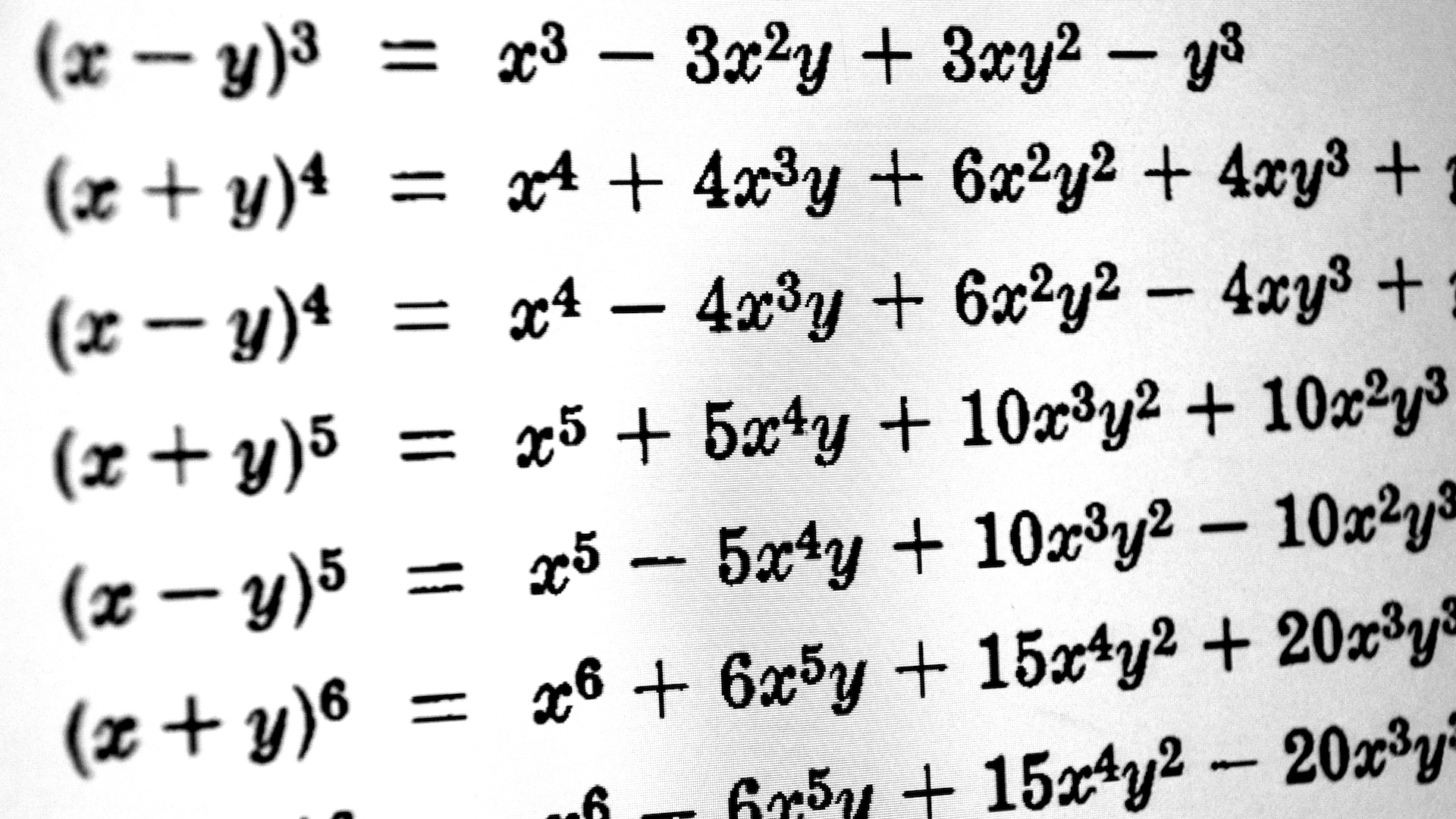

'Dramatic revision of a basic chapter in algebra': Mathematicians devise new way to solve devilishly difficult equations

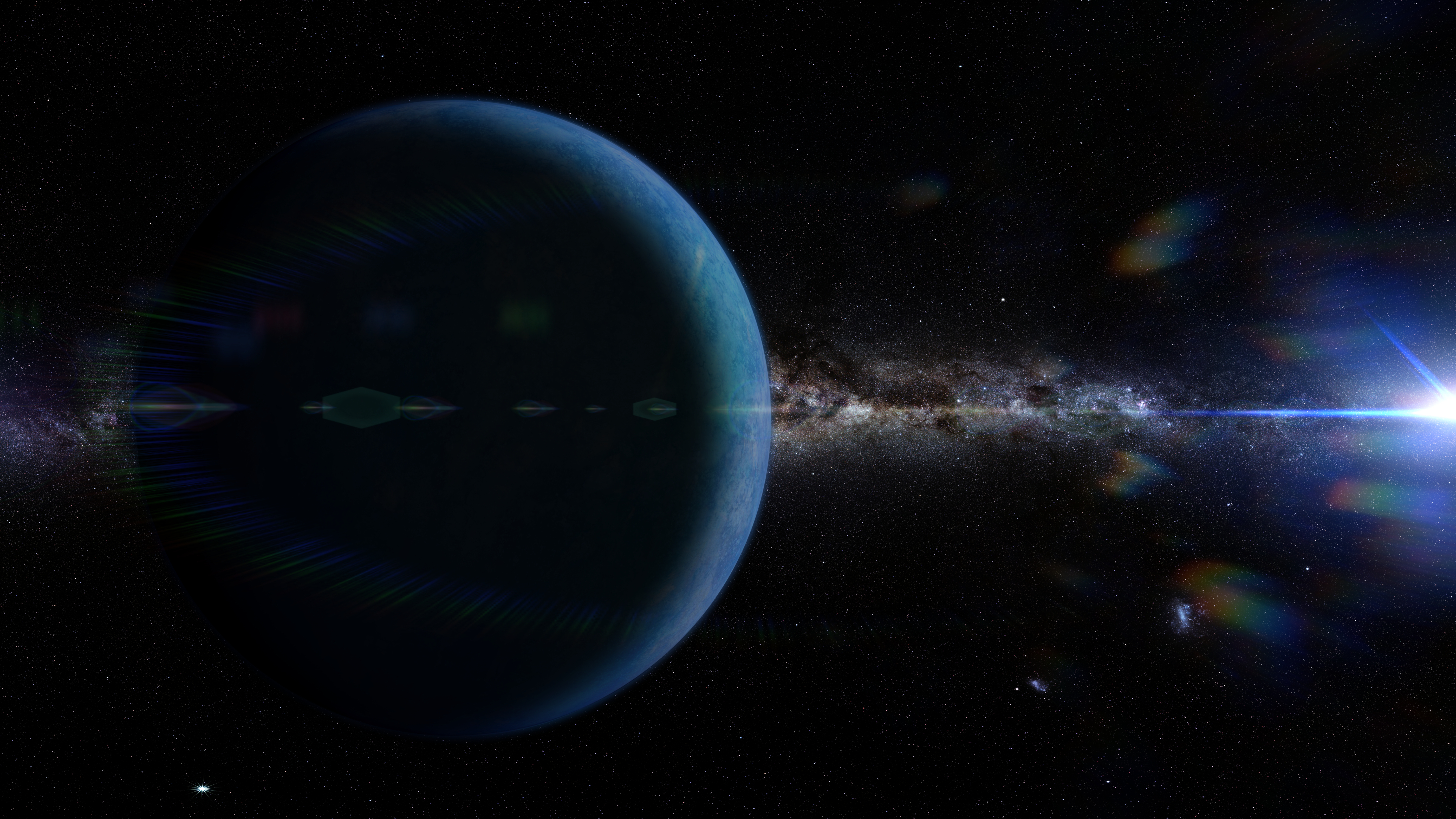

Astronomers identify first 'good' candidate for controversial Planet Nine deep in our solar system

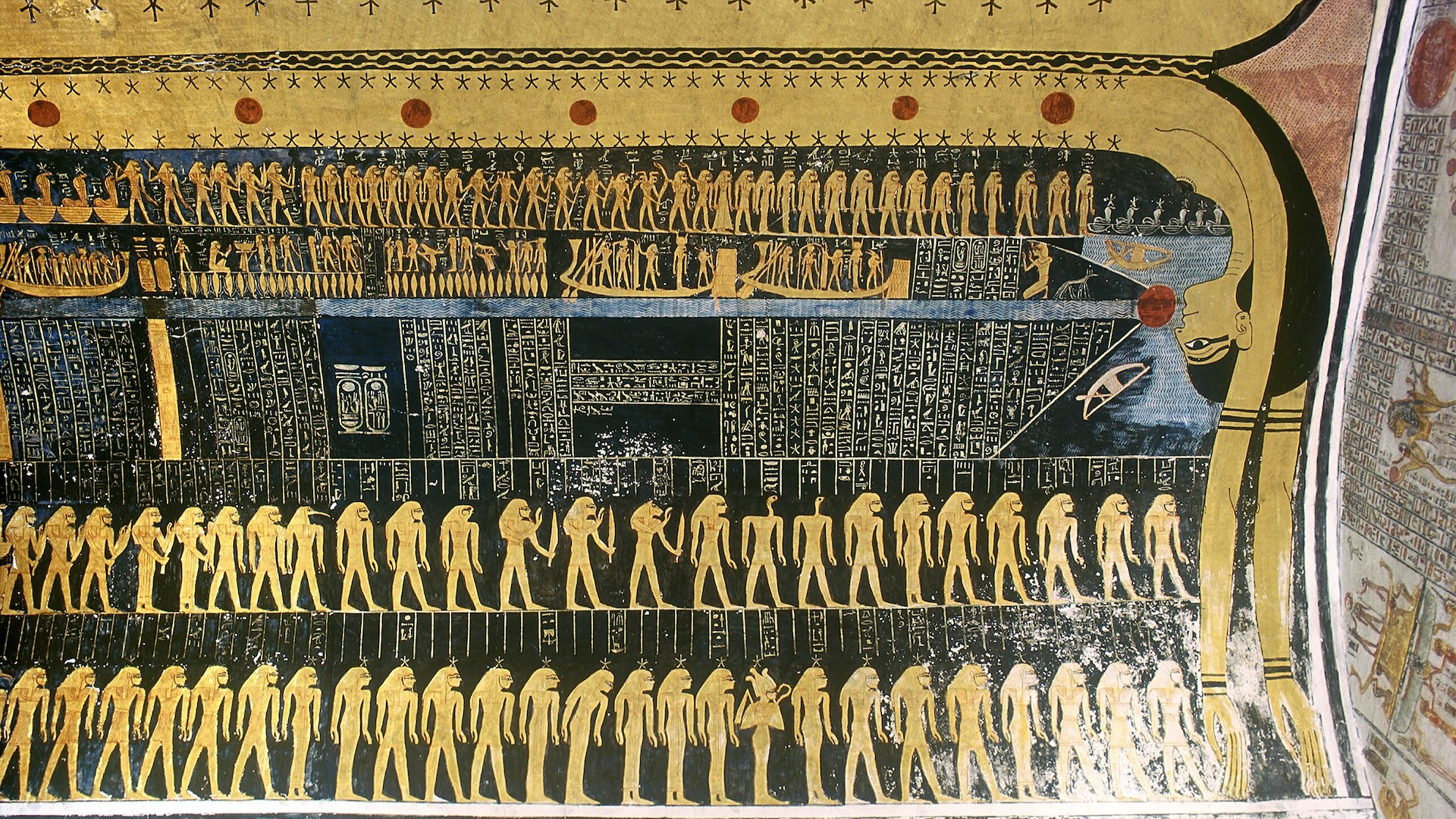

Ancient Egyptians drew the Milky Way on coffins and tombs, linking them to sky goddess, study finds