Strange Lightning Looks Like Jellyfish

An eerie red figure flashed across the sky above a thunderstorm near the south coast of France, and then it was gone in the blink of an eye.

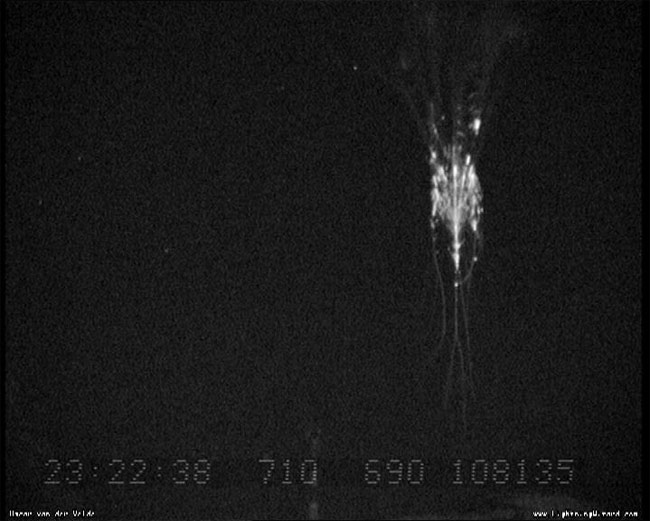

Atmospheric scientist Oscar van der Velde, standing on his balcony in Sant Vicenç de Castellet, in Barcelona, Spain, captured the sprite, as it is called, in spectacular detail on the night of June 5. He was more than 150 miles (250 km) away from the storm.

"It was the sixth sprite that night that I could capture, and the second one at this zoom level," said van der Velde, of the Technical University of Catalonia. "This type of sprite is often called a 'carrot.'"

Lasting just three milliseconds to 10 milliseconds, sprites are flashes of light that occur high above the tops of powerful thunderstorms and can travel up to 50 miles (80 km) high in the atmosphere, emitting deep red to near-infrared light.

"The exciting thing about this one is the level of detail revealed in the sprite by zooming in on the sky above storms," van der Velde told LiveScience. "You have to consider that I obtained the image from my own balcony within a small town with very basic equipment: a security camera fitted with a zoom lens, attached to a laptop with detection software."

(He used UFOCapture, motion capture software that starts recording when luminous phenomena are detected.)

Their brevity and somewhat erratic nature have made sprites elusive study subjects.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In fact, scientists are still trying to figure out just what causes sprites, with some attributing the electrical bursts to lightning and others to meteoric dust, gravity waves or something else completely. The flashes also have been linked with UFO sightings.

"Sprites are very difficult to observe with the naked eye, because they last no longer than the blink of an eye," van der Velde said. "And the light of the lightning flash from the distant storm top underneath is usually catching the attention instead."

He added, "This is also the reason why sprites were discovered only in 1989, which is even later than the discovery of Pluto! Many people, including pilots, have seen these phenomena for decennia [decades], but without proof, scientists remained skeptical."

(In 1989, cameras onboard the STS-34 space shuttle mission recorded sprites as the spacecraft passed over a thunderstorm in northern Australia.)

By studying the structure of sprites, van der Velde said, scientists hope to learn more about lightning, such as cloud-to-ground flashes and so-called spider lightning, among other atmospheric topics.

- Video – Sprite Streamers

- The World's Weirdest Weather

- The Science of Lightning

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.