Microbe Wakes Up After 120,000 Years

After more than 120,000 years trapped beneath a block of ice in Greenland, a tiny microbe has awoken. The long-lasting bacteria may hold clues to what life forms might exist on other planets.

The new bacteria species was found nearly 2 miles (3 km) beneath a Greenland glacier, where temperatures can dip well below freezing, pressure soars, and food and oxygen are scarce.

"We don't know what state they were in," said study team member Jean Brenchley of Pennsylvania State University. "They could've been dormant, or they could've been slowly metabolizing, but we don't know for sure."

Dormant would mean the bacteria were in a spore-like state in which there's not a lot of metabolism going on, so the bacteria wouldn't be reproducing much. It's possible the bacteria could have been slowly metabolizing and replicating.

"Microbes have found ways to survive in harsh conditions for long times that we don't yet fully understand," Brenchley told LiveScience.

To coax the bacteria back to life, Brenchley, Jennifer Loveland-Curtze and their Penn State colleagues incubated the samples at 36 degrees Fahrenheit (2 degrees Celsius) for seven months, followed by more than four months at 41 degrees F (5 degrees C).

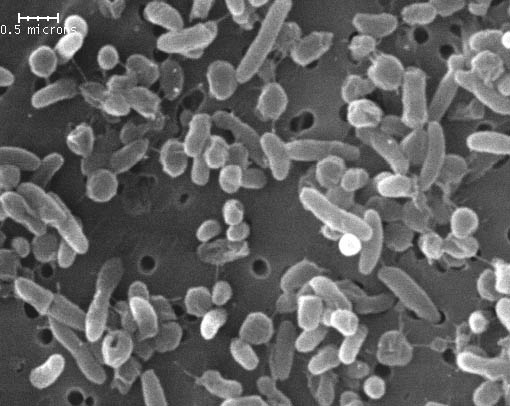

The resulting colonies of the originally purple-brown bacteria, now named Herminiimonas glaciei, are alive and well.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We were able to recover it and get it to grow in our laboratory," Brenchley said. "It was viable."

Such vigor is partially due to the microbe's small size, the scientists speculate. Boasting dimensions that are 10 to 50 times smaller than Escherichia coli, the new bacteria likely could more efficiently absorb nutrients due to a larger surface-to-volume ratio. Tiny microbes like this one can also hide more easily from predators and take up residence among ice crystals and in the thin liquid film on those surfaces.

H. glaciei is not the first bacteria species resurrected after a possibly lengthy snooze beneath the ice. Loveland-Curtze and her team reported another hardy bacterium in the same area that had survived for about 120,000 years as well. Chryseobacterium greenlandensis had tiny bud-like structures on its surface that may have played a role in the organism's survival. Another bacterium survived more than 32,000 years in an Arctic tunnel, and was brought back to life a few years ago.

The harsh conditions endured by these microbes serve as models of other planets.

"These extremely cold environments are the best analogues of possible extraterrestrial habitats," Loveland-Curtze said, referring to the Greenland glacier. "The exceptionally low temperatures can preserve cells and nucleic acids for even millions of years."

And studying such microorganisms may provide insight into what sorts of life forms could survive elsewhere in the solar system.

The new bacterium is described in the current issue of the International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology.

- The Invisible World: All About Microbes

- Bacteria News, Images and Information

- Wild Things: The Most Extreme Creatures

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.