Mars Rover Curiosity Finds Pebbles Likely Shaped by Ancient River

Smooth, round pebbles found by NASA's Mars rover Curiosity provide more evidence that water once flowed on the Red Planet, according to a new study.

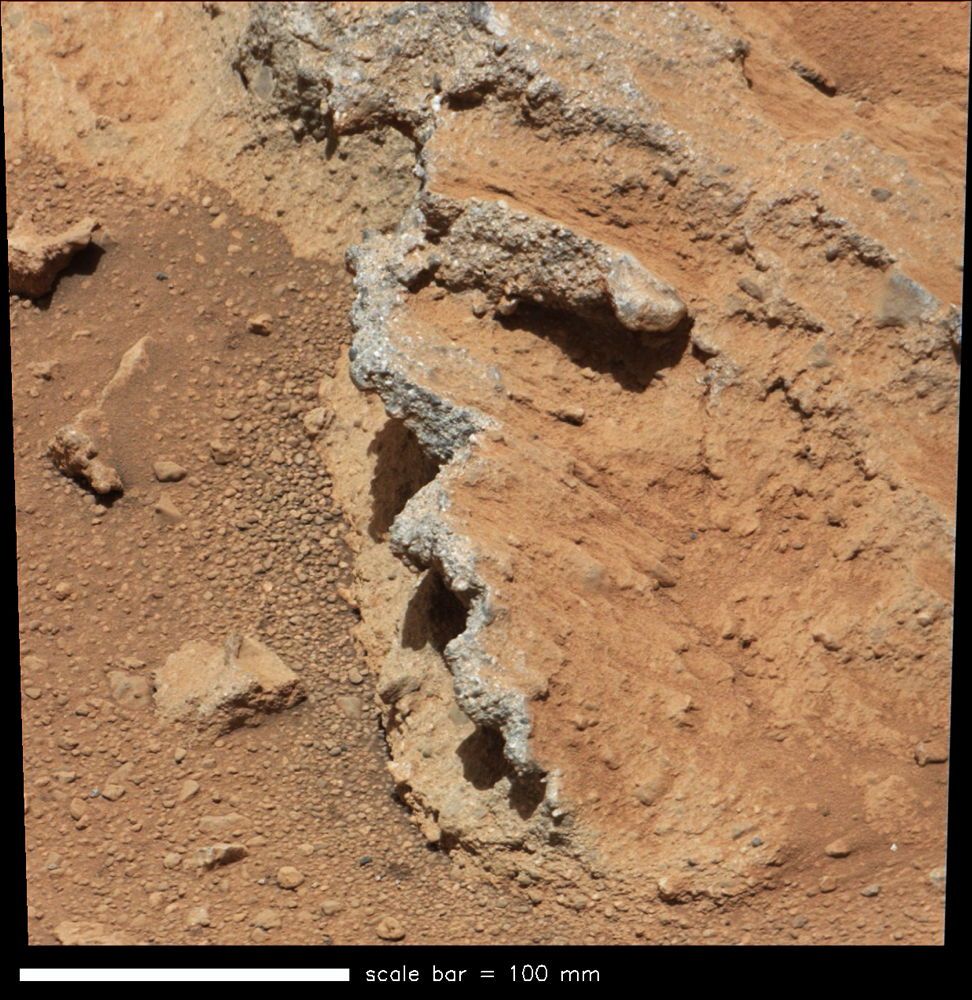

The Curiosity rover snapped pictures of several areas with densely packed pebbles, and by closely analyzing the rock images, researchers discovered that the shapes and sizes of the individual pebbles indicate that they traveled long distances in water, likely as part of an ancient riverbed.

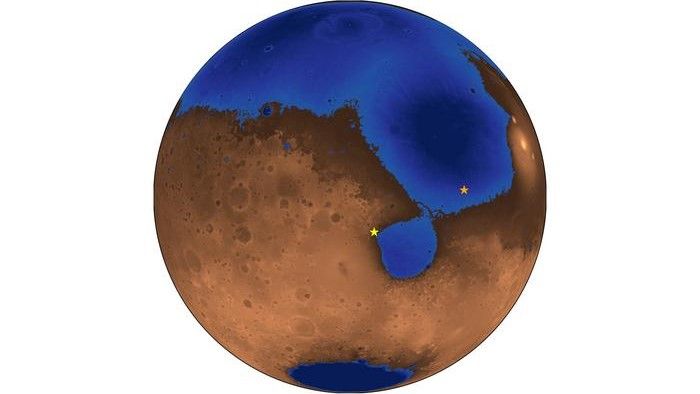

The rocks were found near Curiosity's landing site, between the north rim of Gale Crater and the base of Mount Sharp, a peak that rises 3 miles (5 kilometers) above the crater floor. [Photos: The Search for Water on Mars]

Round and smooth

Scientists divided a photo mosaic of an area called Hottah into smaller frames to study the small rocks, which were cemented together and ranged in size from 0.08 inches (2 millimeters) to 1.6 inches (41 mm) across. In total, the researchers examined 515 stones and noticed that their surfaces were round and smooth.

Rocks worn by wind are typically rough and angular, whereas stones in water tend to become smooth over time, as the rocks get churned around with coarse grains of sand.

"We could see that almost all of the 515 pebbles we analyzed were worn flat, smooth and round," study co-author Asmus Koefoed, a research assistant at the Niels Bohr Institute at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark, said in a statement.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The cemented sections of rock were likely formed by a combination of fine sand, mud, gravel and pebbles, the researchers said. This mixture clumped together and hardened, creating the solid formations seen by the Curiosity rover. Over time, as sand particles were blown across the surface of Mars, the tops of these cemented rocks became worn and flat, the researchers added.

Gale Crater

"The main reason we chose Gale Crater as a landing site was to look at the layered rocks at the base of Mount Sharp, about five miles away," study co-author Dawn Sumner, a geologist at the University of California, Davis, said in a statement. "We knew there was an alluvial fan in the landing area, a cone-shaped deposit of sediment that requires flowing water to form. These sorts of pebbles are likely because of that environment. So while we didn't choose Gale Crater for this purpose, we were hoping to find something like this."

The Martian pebbles offer tantalizing clues about Mars' aqueous past, said Morten Bo Madsen, head of the Mars research group at the Niels Bohr Institute.

"In order to have moved and formed these rounded pebbles, there must have been flowing water with a depth of between 10 centimeters (4 inches) and 1 meter (3.3 feet) and a flow rate of about 1 meter per second — or 3.6 km/h (2.2 mph) — slightly faster than a typical natural Danish stream," Madsen said in a statement.

Scientists have long been interested in the search for water on Mars in order to determine if conditions on the planet were ever hospitable for microbial life.

Although modern-day Mars is an arid place, there is substantial evidence that water likely flowed on the planet's surface several billion years ago. NASA's Spirit and Opportunity rovers, which both touched down on Mars in 2004, found signs of the planet's watery past.

In 2008, the agency's Phoenix Mars Lander confirmed the existence of current water-ice on Mars, after it scraped away clumps of dirt on the surface of the Red Planet.

The results of the new study show that Curiosity, which was launched in August 2012, has already achieved one of its main objectives: to investigate whether areas of Mars could have been habitable for ancient microbial life. The answer, apparently, is yes.

The results of the new study will be published in the May 31 issue of the journal Science.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Denise Chow was the assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. Before joining the Live Science team in 2013, she spent two years as a staff writer for Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University.