Incredible Technology: How to Explore Antarctica

Editor's Note: In this weekly series, LiveScience explores how technology drives scientific exploration and discovery.

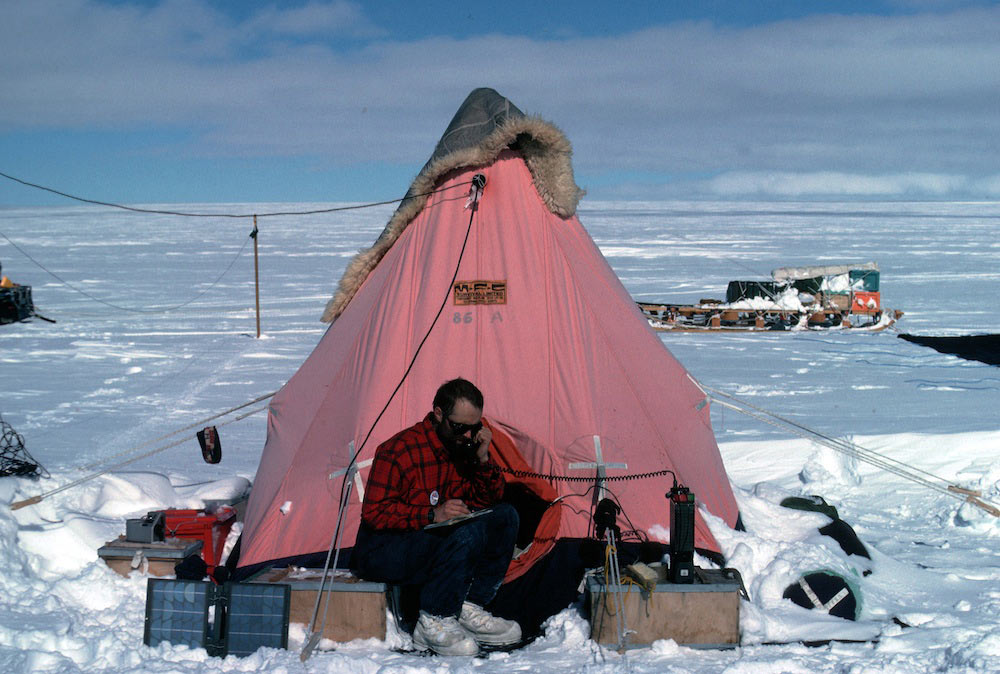

Humanity has landed robots on Mars and invented technologies capable of building materials from atoms up. But when exploring the iciest continent on Earth, humans are often surprisingly low-tech.

Oh, you're going to want polar fleece. Gore-Tex, too. And avoid cotton — as soon as it gets wet in the Antarctic wind, you'll be shivering your way to hypothermia.

Beyond synthetic fabrics, though, much of the technology used to survive in Antarctica is nothing new. Even the tents used to camp on the ice are not appreciably different from the ones Robert Falcon Scott and his team slept in more than a century ago when they led some of the first expeditions onto the icy continent, according to Robert Mulvaney, a glaciologist with the British Antarctic Survey. [Image Gallery: One-of-a-Kind Places]

"We do now use skidoos rather than dogs to pull the sledges!" Mulvaney told LiveScience.

In many ways, the British Antarctic Survey typifies the Antarctic experience: Exploring the continent involves a mix of old (paraffin stoves, aircraft with three decades of flight under their wings) and new (ultra-precise GPS devices, satellite imagery and drilling techniques that allow researchers to sample deep into the ice). What hasn't changed is that Antarctica is in many ways one of the most mysterious places on Earth.

Exploring on ice

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

There's no doubt that technology has made trips to Antarctica easier. Scott's ill-fated Terra Nova Expedition of 1910-1912 saw the explorer packing ponies and dogs, while modern scientists travel by plane, helicopter and snowmobile. Scott and his party perished in a blizzard, with Scott scribbling out letters to family, friends and military commanders that he could only hope would be found later. Today, even Antarctica has the Internet.

But on the ground, technology doesn't necessarily rule. Christian Sidor, a biologist at the University of Washington and a research associate at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, has done paleontological excavations in Antarctica, searching for the ancestors of dinosaurs that roamed the area when it was part of the super-continent Pangea.

"The biggest difference is probably that where I do fieldwork elsewhere, it's all based on trucks and walking," Sidor told LiveScience. "In Antarctica, for the most part, especially in the Central Transantarctic Mountains, we basically get dropped off by helicopter."

The helicopter and snowmobiles make for an easier commute than sled dogs, but once Sidor and his colleagues are at their excavation sites, they keep things simple. Rock saws and jackhammers help them collect fossils, and a satellite phone keeps them in communication with the outside world, if necessary. The most useful high-tech tool the team uses is GPS, Sidor said. The precision of the devices is now so advanced that if you leave a GPS on a fossil discovery for 15 to 20 minutes, it can pinpoint that location down to 4 to 8 inches (10 to 20 centimeters).

GPS is a boon to geologists, too, said Dave Barbeau, a geoscientist at the University of South Carolina and the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory in New York. Nevertheless, Barbeau and his team still collect samples the old-fashion way — with rock hammers and muscle power.

"Things are more efficient, more productive, etcetera, but using similar techniques that we've been using for decades, if not more than a century in some cases, for rock-based geology work," Barbeau said.

In part, he added, the old-fashion techniques are still useful because the geology of Antarctica is still so unknown.

"You need to do theseveral decades to century-old type of geology," he said. "Things that were done in the Appalachians 100 years ago are still needing to be done in Antarctica."

Digging deep with big technology

Other Antarctic discoveries would be impossible without sophisticated technology. Advances in drilling have allowed scientists to peer deep into Antarctica's geologic and climatalogical past. The ANDRILL (Antarctic Geological Drilling) project broke records when it drilled 4,219 feet (1,286 meters) below the seafloor beneath the McMurdo Ice Shelf in the Southern Hemisphere summer of 2006-2007. The ice shelf itself floats over almost 3,000 feet (900 m) of water, making the project even more challenging.

Satellite imaging has also made it easier to trace modern-day changes in Antarctic ice. The European satellite Envisat, for example, has been documenting the loss of ice from the Larsen ice shelffor more than a decade. [Images of Melt: Earth's Vanishing Ice]

Many researchers custom-build their own technology to fit their scientific needs. Custom-built cameras can photograph the water column from onboard research vessels, said Cassandra Brooks, a doctoral student from Stanford University who recently returned from a National Science Foundation expedition aboard the icebreaker Nathanial B. Palmer. The Stanford researchers, meanwhile, used specially designed onboard lab equipment to measure dissolved carbon in the water.

"It's pretty neat when you have people who know the system so well they can actually design the machine to do all the grunt work for you," Brooks told LiveScience.

On the other hand, sometimes the best technology is whatever is on hand. During the voyage, Brooks said, the scientists noticed that some of the pancake ice on the Ross Sea was unexpectedly glowing green — a sign of an unusually late phytoplankton bloom. No one had planned to study this unexpected phenomenon, but that doesn't mean the researchers were about to let the opportunity pass them by.

"People were collecting old mayonnaise jars from the galley and putting them over the edge on poles to try to collect this green pancake ice," Brooks said. "It was hysterical."

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitterand Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook& Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.