Causes of Global Warming

Earth's climate has always been in a state of flux, according to data gleaned from the geological record, ice core samples and other sources. However, since the Industrial Revolution began in the late 1700s, the world's climate has been changing in a rapid and unprecedented way.

The average global temperature has risen 1.4 degrees Fahrenheit (0.8 degrees Celsius) since 1880, according to NASA. Temperatures are projected to rise another 2 degrees to 11.5 degrees F (1.13 degrees to 6.42 degrees C) over the next 100 years, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Some have confused global warming as persistent, increasing warmth. Though one of the effects of global warming in an increase in global temperature, that may not translate to a higher temperature in an individual location. "Global warming is important because it is so persistent and global in scale, and because it brings more extreme events such as heat waves — not because it makes every place warm all the time. It doesn't do that," said atmospheric scientist Adam Sobel, author of "Storm Surge: Hurricane Sandy, Our Changing Climate, and Extreme Weather of the Past and Future" (HarperWave, 2014). In addition to heat waves, the increase in global temperature is having a massive effect on the environment, such as melting polar ice caps, raising the sea level and fueling dangerous and severe weather patterns. Understanding the causes of global warming is the first step to curbing its effects.

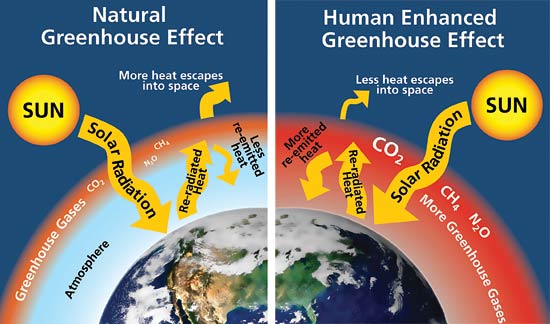

The greenhouse effect

Earth's climate is the result of a balance between the amount of incoming energy from the sun and energy being radiated out into space.

Incoming solar radiation strikes Earth's atmosphere in the form of visible light, plus ultraviolet and infrared radiation (which are invisible to the human eye), according to NASA's Earth Observatory.

Ultraviolet (UV) radiation has a higher energy level than visible light, and infrared (IR) radiation has a lower energy level. Some of the sun's incoming radiation is absorbed by the atmosphere, the oceans and the surface of the Earth.

Much of it, however, is reflected out to space as low-energy infrared radiation. For Earth's temperature to remain stable, the amount of incoming solar radiation should be roughly equal to the amount of IR leaving the atmosphere. According to NASA satellite measurements, the atmosphere radiates thermal IR energy equivalent to 59 percent of the incoming solar energy.

As Earth's atmosphere changes, however, the amount of infrared radiation leaving the atmosphere also changes. Since the Industrial Revolution, the burning of fossil fuels such as coal, oil and gasoline have greatly increased the amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere, according to NASA's Earth Observatory. Before the industrial revolution, during warm interglacial periods, the concentration of CO2in the atmosphere hovered around 280 parts per million (ppm). A NASA graph shows the rapid increase in this greenhouse gas since then: In 2013, CO2 hit 400 ppm for the first time. In April 2017, the concentration hit 410 ppm for the first time in recorded history. The director of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography CO2 group wrote at the time that levels are expected to hit 450 ppm by 2035, unless greenhouse gas emissions drop significantly.

Along with other gases like methane and nitrous oxide, CO2 acts like a blanket, absorbing infrared radiation and preventing it from leaving the atmosphere. The net effect causes the gradual heating of Earth's atmosphere and surface. [Related: Effects of Global Warming]

This is called the "greenhouse effect" because a similar process occurs in a greenhouse: Relatively high-energy UV and visible radiation penetrate the glass walls and roof of a greenhouse, but weaker IR can't pass through the glass. The trapped infrared keeps the greenhouse warm, even in the coldest winter weather.

Greenhouse gases

There are several gases in Earth's atmosphere known as "greenhouse gases" because they exacerbate the greenhouse effect: Carbon dioxide (CO2), methane, nitrous oxide, water vapor and ozone are among the most prevalent, according to NASA.

Not all greenhouse gases are the same: Some, like methane, are produced through agricultural practices including livestock manure management. Others, like CO2, largely result from natural processes like respiration and from the burning of fossil fuels.

Additionally, these greenhouses gases don't contribute equally to the greenhouse effect: Methane, for example, is about 20 times more effective at trapping heat from IR than carbon dioxide, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). This difference in heat-trapping ability is sometimes referred to as a gas's "global-warming potential," or GWP.

CO2 is the most common greenhouse gas in the atmosphere. In 2012, CO2 accounted for about 82 percent of all U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, according to the EPA. "We are burning fossil fuels at a high rate, putting more and more CO2 into the atmosphere. This is causing warming to increase, exactly as theorized long ago. There is no question about this at all," Josef Werne, a professor of geology and environmental science at the University of Pittsburgh, told Live Science.

Methane (CH4) is the second most common greenhouse gas. Methane accounted for around 9 percent of all U.S. greenhouse gas emissions in 2012, according to the EPA. Mining, the use of natural gas, landfills and the mass raising of livestock are some ways that methane is released into the atmosphere. Humans are responsible for 60 percent of the methane in the atmosphere, according to the EPA.

Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), chemicals used as refrigerants and propellants, are another major human-sourced greenhouse gas. The use of CFCs was phased out in the 1990s after the discovery that they eat away at the ozone, an atmospheric layer made of three oxygen atoms that shields the Earth's surface from ultraviolet radiation. The hole in the ozone layer still persists, as do some long-lasting CFCs in the atmosphere, but CFCs are a success story, according to NOAA. Their levels in the atmosphere are now either stable or declining.

In 2015, electricity production (60 percent of which is generated by fossil fuel burning) accounted for largest share (29 percent) of greenhouse gas emissions that year, according to the EPA. That was followed by transportation, which accounted for 27 percent of 2015's greenhouse gas emissions; industry (21 percent); businesses and homes (12 percent); and agriculture (9 percent). Because trees act as a sink for carbon dioxide, " managed forests and other lands have absorbed more CO2 from the atmosphere than they emit," an offset of about 11.8 percent of 2015's greenhouse gas emissions, the EPA said.

Natural causes vs. human causes

Earth's historic climate changes have included ice ages, warming periods and other fluctuations in climate over many centuries. Some of these historical changes can be attributed to changes in the amount of solar radiation hitting the planet. A drop in solar activity, for example, is believed to have caused the "Little Ice Age," a period of unusually colder climate that lasted from about A.D. 1650 to 1850, according to NASA. However, there is no evidence that any increase in solar radiation could be responsible for the steady increase in global temperatures that scientists are now recording, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

In other words, natural causes cannot be held responsible for global warming. "There is no scientific debate on this point," NOAA says.

Indeed, virtually every credible source of scientific research from around the world indicates that human causes, primarily the burning of fossil fuels and the subsequent increase in atmospheric CO2 levels, are responsible for global warming. Some of these organizations are the American Medical Association, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, American Association for the Advancement of Science, Ecological Society of Australia, American Chemical Society, Geological Society of London, American Geophysical Union, International Arctic Science Committee, American Meteorological Society, American Physical Society, and The Geological Society of America. Over 197 international organizations agree on this point.

"In all honesty, anthropogenic (human-caused) climate change is not a scientific debate, it is a political/economic debate," Werne said. According to Werne, the relevant question is not, "Is there human-induced climate change?" The question that we should be focused on is, if anything, "What should we do about human-induce climate change?"

Editor's Note: Stephanie Pappas and Marc Lallanilla contributed to this article.

For the latest information on the greenhouse effect, visit:

Additional resources

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.