New MS Treatment 'Tricks' Immune System

An experimental treatment that involves injecting multiple sclerosis (MS) patients with their own white blood cells has been shown to be safe, according to a new study. The study also provided some evidence that the treatment was effective in modifying the immune system.

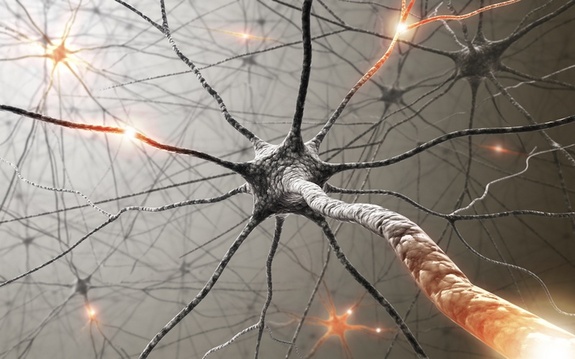

MS arises when a person's immune system attacks myelin, the insulating sheath surrounding neurons. In the study, portions of myelin proteins were attached to the surface of the white blood cells of nine patients. The treated blood cells were then injected back into the patients, in order to "educate" the immune system's T cells not to attack these myelin proteins.

The patients didn't experience adverse effects related to the treatment, the researchers said. A concern was that the treatment might compromise the immune system, leaving the patients vulnerable to infections.

Although the study was designed to test only the treatment's safety, and not whether it could effectively combat the disease, the researchers found that patients who received the highest doses of the treatment showed enhanced immune tolerance for myelin, according to the study published today (June 5) in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

In people with MS, as damage to myelin progresses, neurons can't communicate effectively, which results in a wide range of symptoms, including numbness, neurological deficits, blindness and paralysis.

"What we are doing is essentially tricking the immune system," into thinking myelin is no longer a threat, said study researcher Stephen Miller, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago.

Currently, the main treatment for patients suffering from acute MS attacks involves broadly suppressing the immune system, which makes patients vulnerable to infections and cancer.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The new approach aims to suppress only the immune response to myelin. To teach T cells that myelin is harmless, the researchers attached bits of myelin to the blood cells. This also causes the cells to later self-destruct, in a process called apoptosis. When infused back into the patient, the dead and dying blood cells get eaten up by large immune-system cells called macrophages in the spleen and liver.

"The immune system has evolved in such a way that apoptotic cells are not seen as a threat,” Miller said. “Therefore, rather than inducing an immune response, they actually induce tolerance."

The patients in the study received varying doses of the treatment. Three months later, the immune systems of the patients who got the highest doses — up to 3 billion treated blood cells — became less reactive to myelin proteins but could still fight other pathogens.

Myelin is made of different proteins, and which ones are targeted by the immune system can vary in different MS patients, and over time. Researchers believe that as the damage to the myelin sheath progresses, T cells start to attack new groups of myelin proteins, and this triggers a relapse of the disease.

The researchers said the new treatment is more likely to be effective if it’s given when the disease is in its earlier stages, before the T cells become reactive to more and more myelin proteins. The other reason to intervene early is that the treatment cannot not repair myelin damage that has already occurred. "Myelin is very hard to repair once it's damaged, so we try to stop the disease as soon as possible," Miller said.

Now that the treatment is deemed safe in humans, the researchers are planning to conduct a larger study with more patients and a longer follow-up. "It's going to take a lot more patients to come to firm conclusions," Miller said.

The treatment is costly and complex, the researchers said. They are hopeful that the same treatment could be developed using nanoparticles instead of blood cells and achieve the same results, and this method could be less expensive and simpler.

In a study published last year in the journal Nature Nanotechnology, the researchers showed that they were able to attach antigens to biodegradable nanoparticles, and induce tolerance to myelin in mouse models of MS.

And although this would happen much further down the road, the new treatment could potentially be useful for other autoimmune diseases, such as diabetes, by switching the protein attached to the white blood cells, the researchers said. "For example, in type 1 diabetes, we could attach insulin, or in allergy [patients], we could use peanut antigens," Miller said.

The study was a collaboration among researchers at Northwestern University, the University Hospital Zurich in Switzerland, and the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf in Germany.

Email Bahar Gholipour. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science .