How Birds Lost Their Penises

How did the chicken lose its penis? By killing off the growing appendage in the egg.

That's the finding of a new study, which reveals how most birds evolved to lose their external genitalia. Turns out, a particular protein released during the development of chickens, quail and most other birds nips penis development in the bud, according to the new research, published today (June 6) in the journal Current Biology.

The findings have implications for genital development in general, which is important because birth defects in the external genitalia are among the most common congenital defects in humans, said study researcher Martin Cohn, a developmental biologist at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the University of Florida.

"Comparative evolutionary studies of development allow us to understand not only how evolution works, but also gives us new insights into the possible causes of malformations," Cohn told LiveScience.

Missing penises

About 97 percent of birds lack penises entirely. The exceptions are real odd ducks — literally. Some waterfowl have coiling penises that can exceed the length of the rest of their bodies. [Whoa! The 9 Weirdest Animal Penises]

The most primitive group of birds, paleognaths, which include emus, kiwis and ostriches, have well-developed phalluses, as well. Along the evolutionary line, two newer groups diverged: anseriformes, which include penis-wielding ducks, swans and geese, and galliformes, which make up most land-loving birds and lack penises.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To understand how this genital gap diverges in development, Cohn, along with research assistant Ana Herrera and their colleagues, grew embryos from chickens (galliformes) and ducks (anseriformes) and tracked their penis growth.

"It's pretty surprising, actually," Cohn said. "Chickens and ducks start to develop their genitalia in such a similar manner that they're almost indistinguishable."

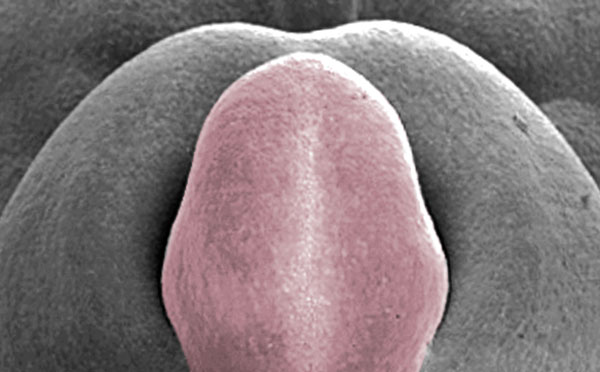

A few days after a primitive penile swelling appears on chick embryos, however, development abruptly halts, and then regresses. By the time they're born, chickens and their galliforme relatives are left with only an opening called the cloaca, rather than an external penis. In duck embryos, the penis continues to grow.

The disappearing phallus

Next, the researchers set out to find out what stops a chick's penis from growing while allowing a duck's to reach startling lengths. They expected to find something missing in chickens — some mysterious molecular factor that would have otherwise spurred the penises to greater lengths.

Instead, the found just the opposite. In chick embryos, penis development is halted by the release of bone morphogenetic protein 4, or Bmp4. This protein shows up along the whole length of the primitive genital swelling seen in early chick development; in ducks, it's only seen at the base of the genitals.

To make sure Bmp4 was really doing the penis-stifling deed, the researchers applied the protein to duck penises. Sure enough, development halted. Likewise, when they blocked Bmp4's expression in chick penises, the embryonic birds' phalluses continued to grow. [See video of the embryonic experiments]

It turns out that Bmp4 is a cell death factor, Cohn said. Its release encourages cells to self-destruct, turning a growing organ into a shrinking one. Cell death is normal in embryos, he said, but it's more typical to see loss of embryonic growth factors in cases where limbs regress in the womb.

"There are many paths to reach the same morphological end," Cohn said.

The new study reveals how birds lost their penises, but not why. It seems odd that birds would evolve to lose an organ so critical to reproduction, Cohn said. Evolutionary biologists have theorized that perhaps bird penises vanished because female birds preferred mates with smaller penises. In ducks and other species with phalluses, males frequently force females to copulate. By picking mates with small penises, female birds could have gained more control over the reproductive process.

Alternatively, penis loss could have been a side effect of other changes in the birds' body. Bmp proteins are responsible for the origin of feathers in birds and their loss of teeth. Bmp4, in particular, is responsible for variations in beak size and shape, Cohn said.

"It's interesting that so many of these little details of the bird body plan are associated with changes in Bmp activity," he said.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.