Weird: Nuclear Bomb Tests Reveal Adults Grow New Brain Cells

Aboveground nuclear bomb testing in the 1950s and 1960s inadvertently gave modern scientists a way to prove the adult brain regularly creates new neurons, research reveals.

Researchers used to believe that the brain changed little once it finished maturing. That view is now considered out of date, as studies have revealed how changeable — or plastic — the adult brain can be.

Much of this plasticity is related to the brain's organization; brain cells can alter their connections and communications with other brain cells. What has been less clear is whether, and to what extent, the human brain grows brand-new neurons in adulthood.

"There was a lot in the literature showing there was neurogenesis in rodents and every animal studied," said study researcher Kirsty Spalding, a biologist at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden, "But there was very little evidence of whether this happens in humans." [Top 10 Mysteries of the Mind]

Tantalizing clues

Scientists had reason to believe it does. In adult mice, the hippocampus, a structure deep in the brain involved in memory and navigation, turns over cells all the time. Some of the biological markers linked to this turnover are seen in the human hippocampus. But the only direct evidence of new brain cells forming in the region came from a 1998 study in which researchers looked at the brains of five people who had been injected with a compounded called BrdU that cells take up into their DNA. (The compound was once used in experimental cancer studies, but is not used anymore for safety reasons.)

The BrdU study revealed that neurons in the hippocampuses of the participants contained the compound in their DNA, indicating these brain cells had formed after the injections. The oldest person in the study was 72, suggesting new neuron creation, known as neurogenesis, continues well into old age.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The 1998 study was the only direct evidence of such neurogenesis in the human hippocampus, however. Spalding and her colleagues wanted to change that. Ten years ago, they began a project to track the age of neurons in the human brain using an unusual tool: spare molecules left over from Cold War-era nuclear bomb tests.

Learning to love the bomb

Between 1945 and 1962, the United States conducted hundreds of aboveground nuclear bomb tests. These tests largely stopped with the Limited Test Ban Treaty of 1963, but their effects remained in the atmosphere. The neutrons sent flying by the bombs reacted with nitrogen in the atmosphere, creating a spike in carbon 14, an isotope (or variation) of carbon. [The 10 Greatest Explosions Ever]

This carbon 14, in turn, did what carbon in the atmosphere does. It combined with oxygen to form carbon dioxide, and was then taken in by plants, which use carbon dioxide in photosynthesis. Humans ate some of these plants, along with some of the animals that also ate these plants, and the carbon 14 inside ended up in their bodies.

When a cell divides, it uses this carbon 14, integrating it into the DNA of the new cells that are forming. Carbon 14 decays over time at a known rate, so scientists can pinpoint from that decay exactly when the new cells were born.

Over the past decade, Spalding and her colleagues have used the technique in a variety of cells, including fat cells, refining it along the way until it became sensitive enough to measure tiny amounts of carbon 14 in small hippocampus samples. The researchers collected samples, with family permission, from autopsies in Sweden.

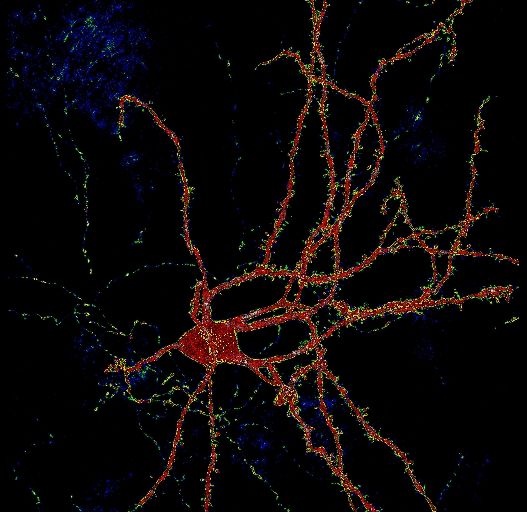

They found the tantalizing 1998 evidence was correct: Human hippocampuses do grow new neurons. In fact, about a third of the brain region is subject to cell turnover, with about 700 new neurons being formed each day in each hippocampus (humans have two, a mirror-image set on either side of the brain). Hippocampus neurons die each day, too, keeping the overall number more or less in balance, with some slow loss of cells with aging, Spalding said.

This turnover occurs at a ridge in the hippocampus known as the dentate gyrus, a spot known to contribute to the formation of new memories. Researchers aren't sure what the function of this constant renewal is, but it could relate to allowing the brain to cope with novel situations, Spalding told LiveScience.

"Neurogenesis gives a particular kind of plasticity to the brain, a cognitive flexibility," she said.

Spalding and her colleagues had used the same techniques in other regions of the brain, including the cortex, the cerebellum and the olfactory bulb, and found no evidence of newborn neurons being integrated into those areas. The researchers now plan to study whether there are any links between neurogenesis and psychiatric conditions such as depression.

The new findings are detailed today (June 6) in the journal Cell.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.