Africa's Worst Drought Tied to West's Pollution

The biggest drought to hit the planet in the 20th century, the Sahel drought sucked Central Africa dry from the 1970s to the 1990s. The severe famines that resulted killed hundreds of thousands of people during this period and gained worldwide attention.

A new study blames the dry spell on pollution in the Northern Hemisphere, primarily from America and Europe. Tiny particles of sulfate, called aerosols, cooled the Northern Hemisphere, shifting tropical rainfall patterns southward, away from Central Africa, according to research published April 24 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

"Even changes from relatively far away spread into the tropics," said Dargan Frierson, a study co-author and climatologist at the University of Washington in Seattle.

At the time, the cooling effect went unnoticed, overshadowed by Earth's overall warming, Frierson said. Instead, the drought was blamed on overgrazing and poor land use practices. But in the past decade, researchers have realized that aerosol pollution plays an important role in Earth's climate, he said. In certain parts of the atmosphere, the tiny particles reflect the sun's light and build longer-lasting clouds, cooling the atmosphere. Not all aerosols reflect light, and the cooling from sulfate particles offsets global warming only a regional scale, because their effects are short-lived and concentrated in high-pollution areas.

"Air pollution affects climate as well, and different parts of the planet are connected in the climate system," Frierson told LiveScience.

To understand the global climate pattern, Frierson and his colleagues first tracked rainfall data worldwide from rain gauge records from the

1930s to the 1990s. They saw the heavy tropical rainfall band called the Intertropical Convergence Zone wander back and forth near the equator, a natural phenomenon, during the 1930s through the 1950s. Ocean currents can affect the position of the rainfall band, giving it year-to-year variability.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

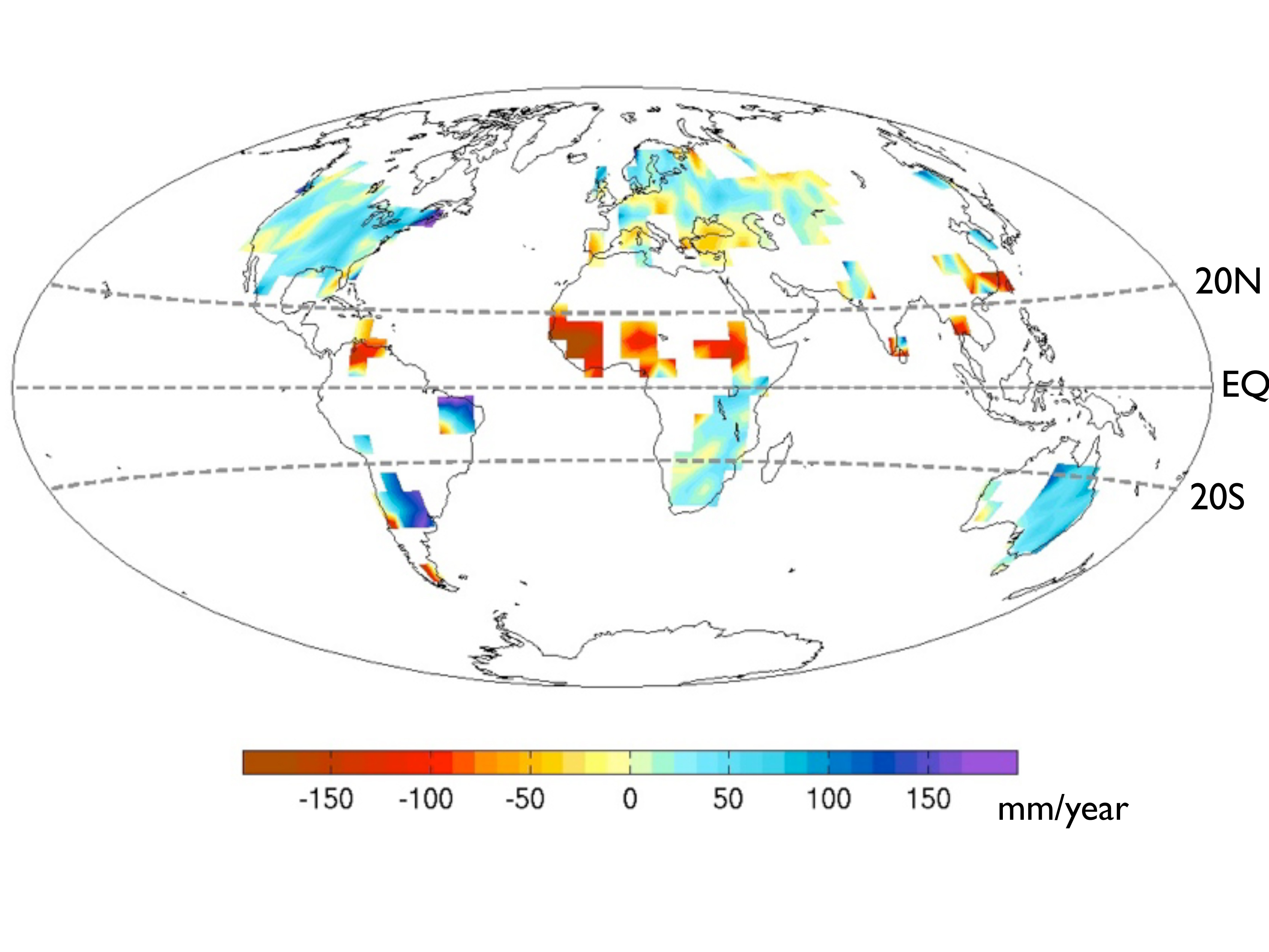

Starting in the 1960s, the rainfall band shifted southward, drying out Central Africa and parts of South America and South Asia, the study found. At the same time, northeast Brazil and Africa's Great Lakes started to see more rain, thanks to the southerly drift. [Dry and Drying: Images of Drought]

The team modeled the reasons for the changing tropical rainfall with all 26 of the climate models used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Every model agreed that sulfate aerosol pollution in the Northern Hemisphere triggered the terrible Sahel drought.

"Precipitation is tough to forecast, and you don't often see all the models agreeing on things like that," Frierson said. "I think it's pretty clear that in addition to greenhouse gases, air pollution really does affect climate, and not just in one place. These emissions over the U.S. and in Europe affected rainfall over Africa," he told LiveScience.

Frierson said cooling in the Northern Hemisphere sent the tropical rainfall band southward until clean air legislation significantly lessened aerosol pollution emitted in North America and Europe. Since the 1990s, tropical rainfall has drifted back toward the north, he said.

The researchers are now studying the global effects of aerosol pollution emitted in Asia.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.