How Remora Fish Get Their Bizarre Suckers

Scientists say they've confirmed how remora fish grow a weird sucking disc on their heads.

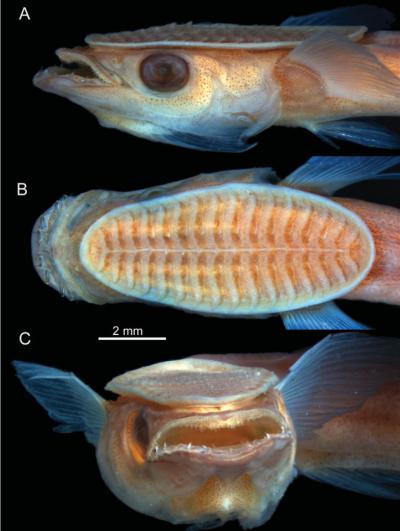

Remoras, which can be up to 3 feet (1 meter) long, have a slatted disc above their eyes, which sort of looks like the bottom of a sneaker. It acts like a sucker and allows them to attach to manta rays, sharks, and boat hulls in tropical waters. But the fish aren't parasites; rather, they harmlessly hitch rides and feed off of scraps of food from their hosts.

It had long been suspected that the sucker was made out of the rearranged parts of a normal dorsal fin, but their development hadn't been studied. By watching remoras grow up from their earliest larva stages, a group of scientists says they finally confirmed that the sucker does indeed come from fin parts.

"We followed the earliest stages of the disc's development by matching the first vestiges of elements of the sucking disc with the first vestiges of elements of the dorsal fins of another fish, the white perch (Morone americana), which has the typical dorsal fin of most fishes," researcher Dave Johnson, zoologist at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History, explained in a statement.

Johnson and colleagues observed that through a series of small changes, three typical fin elements — the distal radials, the proximal-middle radials, and the fin spines — transform during development to form the remora's sucker.

The researchers also found that remora larvae have distinctive hooked teeth protruding from the lower jaw. Johnson says that may be a clue to how the baby fish hitchhike before they grow their suckers.

"Because remora larvae at this stage are relatively rare in plankton collections, I have often wondered, although we don't have any evidence for it, if maybe remora larvae are not free living in the plankton layer but go into the gill cavities of fishes and use their hooked teeth to hang on until they develop a disc," Johnson said in a statement. "Fodder for future research."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The research was detailed in the Journal of Morphology.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.