Magnificent Microphotography: 50 Tiny Wonders

Social Slime Mold

Social amoebae, better known as slime molds, have long been known for their migratory ways. When food gets scarce, they amass and travel to new territory, where they reproduce by sending out spherical fruiting bodies containing spores.

A new study finds that some strains of this social amoeba, called Dictyostelium discoideum, pack bacteria snacks with them before they travel. Once the amoebae reach their destination, they seed the area with the bacteria, ensuring any amoeba offspring will have plenty to eat. Here, the social amoebae fruiting bodies with spores are shown.

Beauty in Embryos

This dreamy illustration of a zebrafish embryo happens to be attached to some cool research. The compilation photo reflects a centuries-old observation that during a certain point in a vertebrate embryo's development, the embryo will look just like embryos of other vertebrates. The concept is known as the "developmental hourglass." Embryos look alike in the middle of development, but early and late in development, the embryos' appearances diverge, just as an hourglass flares out from its narrow "waist."

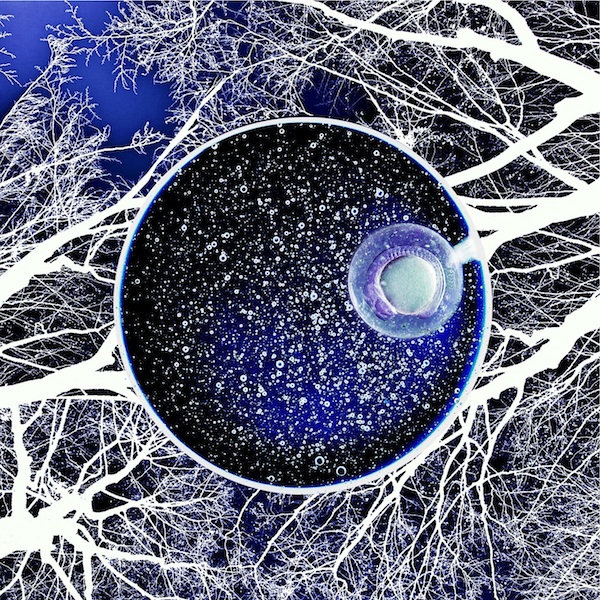

Anarchic Blood Vessels

Blood vessels grow out of control in this environmental scanning electron microscopy image of a diseased retina. In diabetic retinopathy and retinopathy of prematurity, blood vessels grow abnormally in the back of the eye and leak blood, causing blindness. At least 4.1 Americans with diabetes are affected.

Research has shown that inexpensive omega-3 supplements may ease retinopathy. A new study of mice published Feb. 9 in the journal Science Translational Medicine finds that the supplements do so by reducing runaway blood vessel growth. Clinical trials in humans are underway.

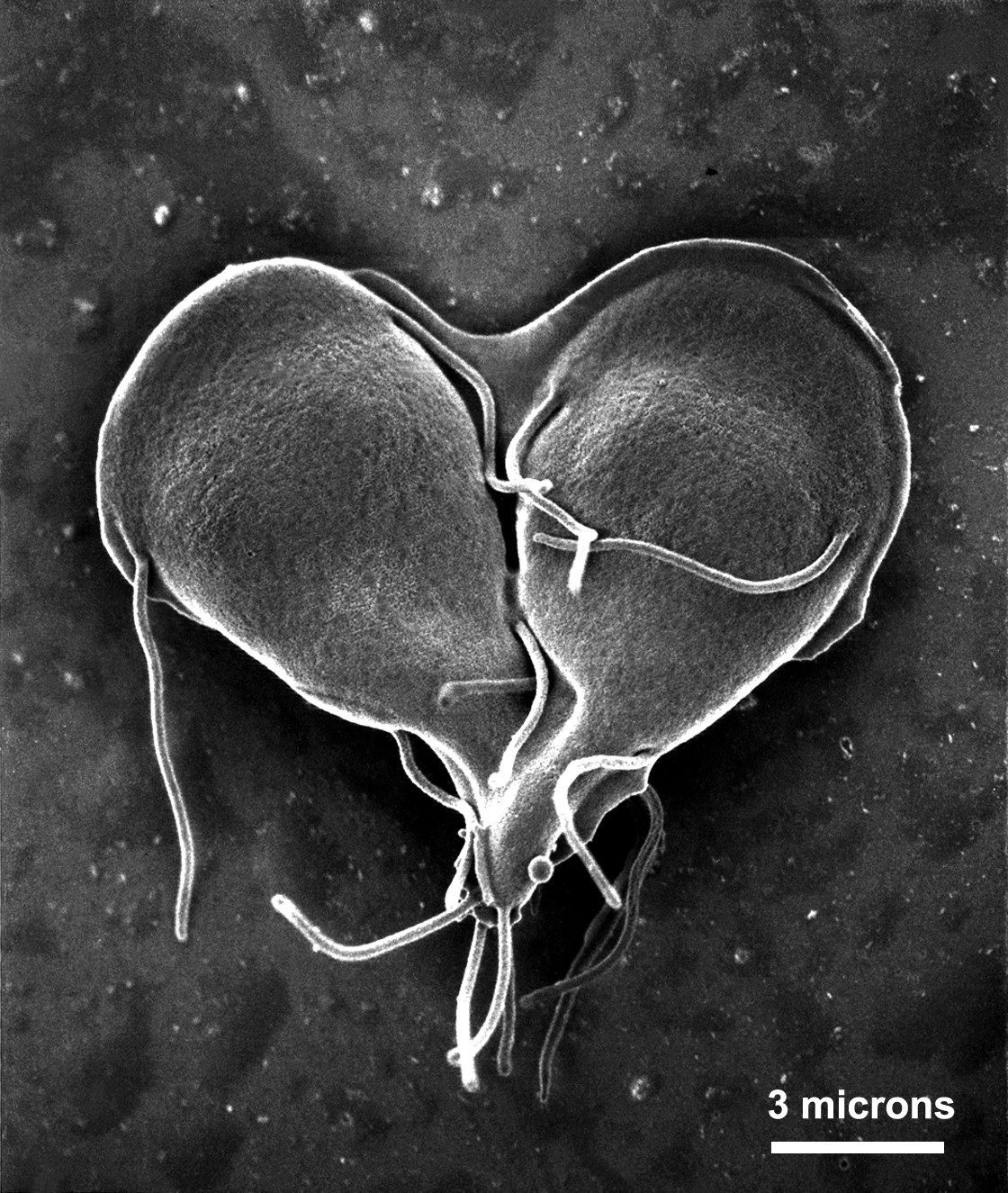

Love in the Time of Giardia

Is it love or a diarrheal parasite? In this Valentine's-appropriate image, it's the parasite. Caught on scanning electron microscope in the midst of dividing into two separate organisms, this Giardia lamblla parasite forms a heart, flagella untwining as the two new protozoa prepare to go their separate ways. When ingested by humans (usually through drinking contaminated water), Giardia protozoa cause a diarrheal disease called giardiasis.

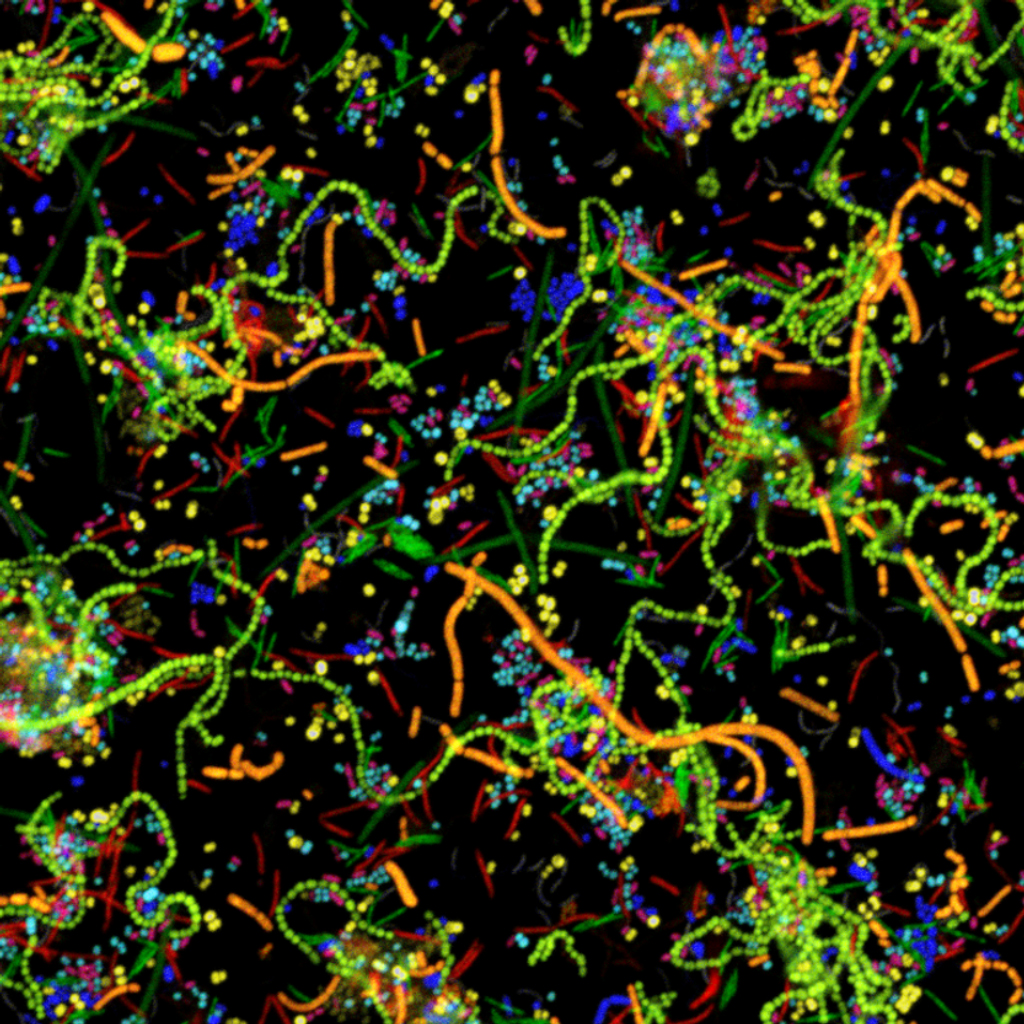

Favorite Microbe Hangouts

Microbes crawling around our bodies gravitate to and "hang out" with certain other types of bacteria in their little community. Researchers have known this much about microbes. But until now they could not see these cliques in action. A new microscope technique called CLASI-FISH (combinatorial labeling and spectral imaging fluorescent in situ hybridization), gave scientists at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Mass., a peak at the spatial arrangement of up to 20 microbes in a single field of view. They used the technique to analyze dental plaque, a complex biofilm known to contain at least 600 species of microbes. They were able to visually discriminate 15 different microbial types (shown here), and to determine which two types – Prevotella and Actinomyces – showed the most interspecies associations.

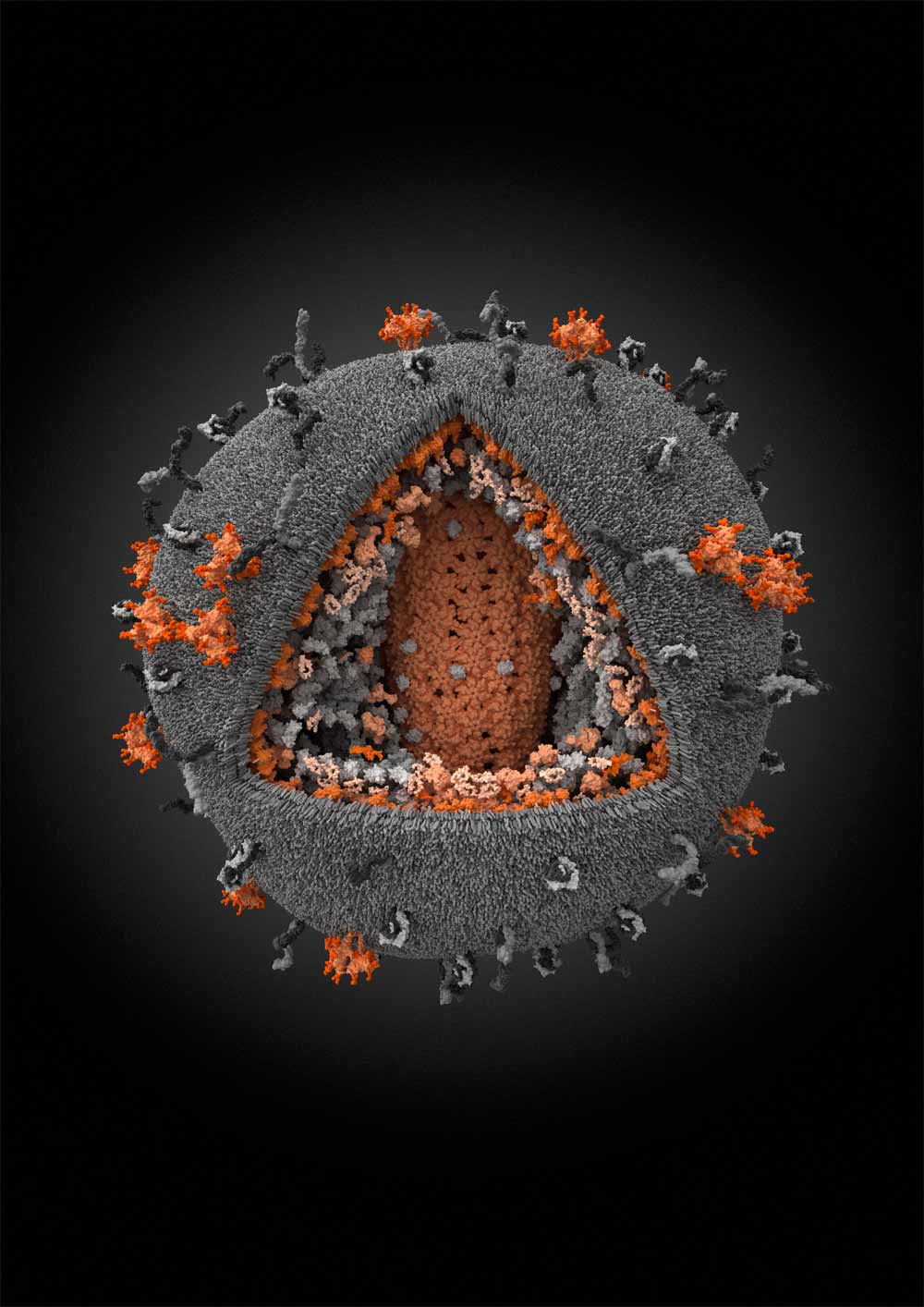

Viral Impact

A detailed 3-D model of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) won first prize in the 2010 International Science and Engineering Visualization Challenge, sponsored jointly by the journal Science and the National Science Foundation (NSF), announced Thursday (Feb. 17).

Currently in its eighth year, the international competition honors recipients who use visual media to promote understanding of scientific research. The criteria for judging the entries included visual impact, effective communication, freshness and originality.

That was surely the case for the HIV illustration. Ivan Konstantinov and his team's winning illustration depict the most highly detailed 3D structural model of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) ever made. "We consider such 3-D models as a new way to present and promote scientific data about ubiquitous human viruses," said Ivan Konstantinov, one of the scientists who created the illustration.

Konstantinov said his team tried to show the viral particle in as real a light as possible. "While working on the HIV model, over 100 articles from leading scientific journals were analyzed," he said. "For this project, Dr. Yegor Voronin from the Global HIV Vaccine Enterprise helped us evaluate the data, shared recent findings and views in the field, and provided general advice."

Small Packages

Phytoplankton never looked so sparkly. These diatoms, or single-celled algae species, glitter under the microscope like tiny jewels. Diatoms form the basis of many a marine food chain, and they're protected by cell walls made of silica, seen here. When diatoms die, their cell walls form diatomaceous earth, a sediment used in pool filters and some kitty litter. Researchers use diatom deposits as one way to understand the conditions of ancient lakes and bogs.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

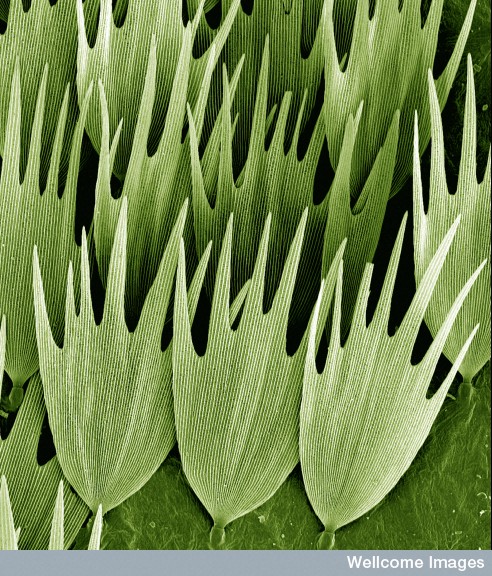

Ephemeral Beauty

The scales of a moon moth look like palm fronds under the electron microscope. Moon moths, native to Madagascar, don't have mouths. They do all their eating as larvae. After their metamorphosis into fluttering moths, they live only 10 days.

The image snagged a spot on the Wellcome Image Awards 2011, which chooses the most striking and technically excellent images acquired by the Wellcome Images picture library in the prior 18 months.

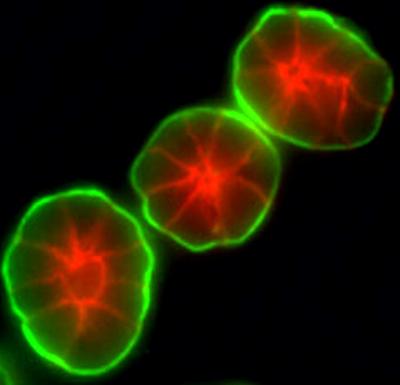

Cellular Starbursts

Three breast cells grown in a lab reveal the trademark starburst shape of a protein called laminin. Like the framework of a house, laminin provides support to body tissue. A new study from UC Berkeley researchers finds that laminin's interactions with other cellular proteins are also key to the development of breast cancer. The findings are far from being translated into a treatment for breast cancer, but the researchers say the study gives them new molecular targets to investigate.

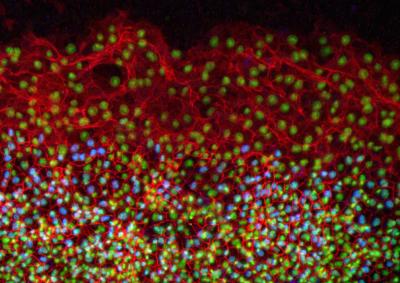

How Does Your Embryo Grow?

Ultra-magnified, a quail embryo reveals the secrets of its rapid growth. According to a new study published in the journal Developmental Dynamics, the radius of the quail yolk doubles every day for the first few days of development, representing a hundreds-fold increase in the egg yolk surface area. For the cells that have to cover that yolk as it grows, the migration across its expanse is "like an ant walking across the earth," study researcher Evan Zamir of Georgia Tech said in a statement.

The new study finds that the cells at the edges of the sheet covering the yolk don't divide. Instead, actively dividing cells in the interior (shown here in blue, purple and orange) migrate out to grow the sheet. But the study isn't just an excuse to label cells with pretty colors; researchers hope an understanding of how cells migrate over large distances will help them develop treatments for wound healing and cancer.

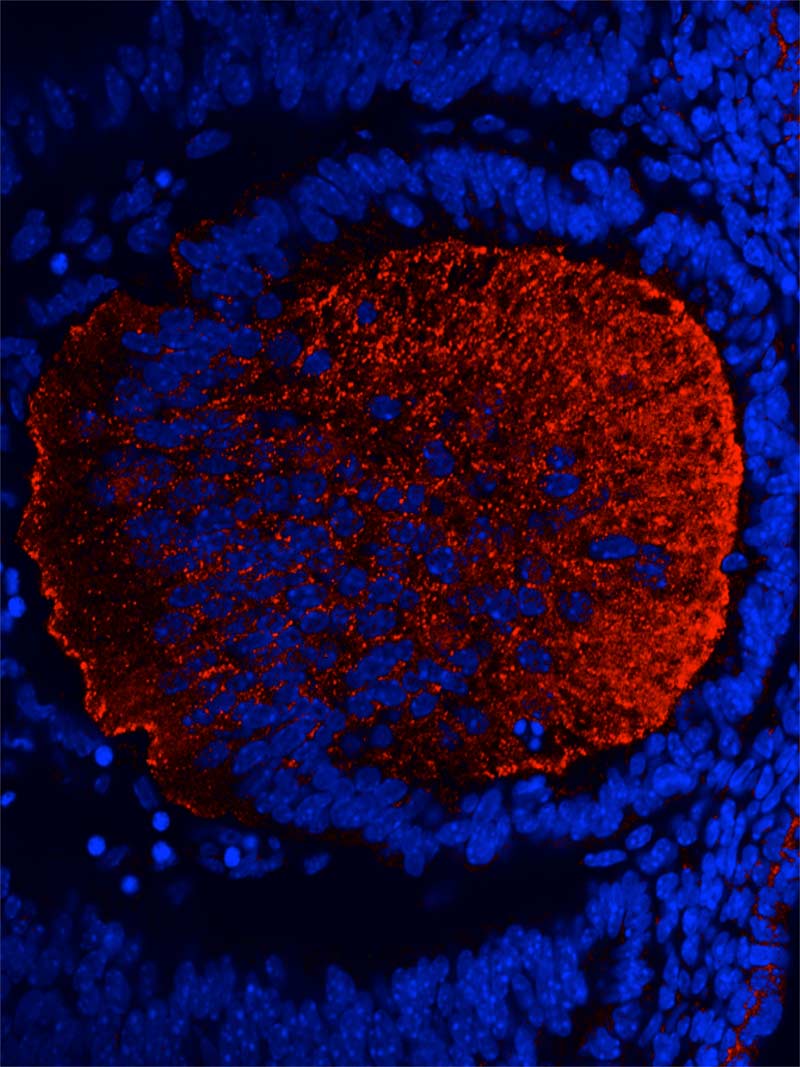

Mouse Vision

Here, the ocular lens from a 12-day-old mouse embryo shows expression of a protein called TDRD7 in specialized lens fiber cells, forming foci of so-called RNA granules (stained here in red). The nuclei of the fiber cells are stained blue. Research published in the March 24, 2011, issue of the journal Nature revealed that mice without the protein develop cataract and glaucoma. Mutations in the protein in humans can also lead to cataract, they found.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.