Earthquake Sounds Its Own Tsunami Warning

Death by drowning was the biggest killer in the 2011 Japan earthquake and tsunami.

Since the disaster, scientists have analyzed the massive Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, seeking better ways to predict these dangerous waves. Based on computer modeling, scientists at Stanford University now think sound waves from big earthquakes such as Japan's could provide 15 to 20 minutes of advance notice before a tsunami hits, according to a study published in the June 2013 issue of the journal the Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. (Some towns on the Japan coastline had just 10 minutes to flee before the tsunami arrived.)

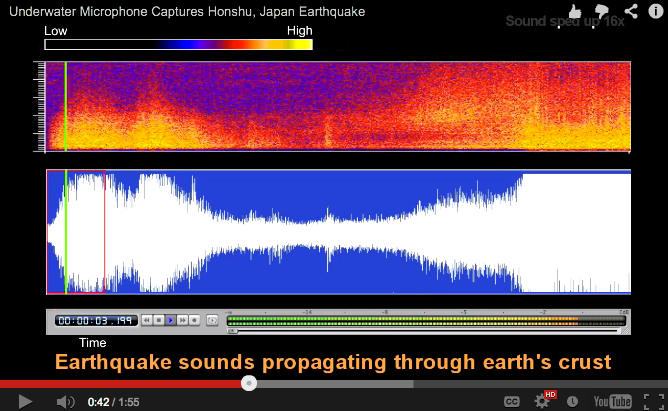

Along with seismic shaking, undersea earthquakes also produce low-frequency sound waves that travel through the ocean. The size of the sound signal is linked to the earthquake's magnitude. The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) uses a network of underwater microphones called hydrophones to listen for offshore earthquakes and volcanic eruptions.

The size of tsunami waves also appears to be linked to the acoustic signals produced by earthquakes, according to the new study.

"We've found that there's a strong correlation between the amplitude of the sound waves and the tsunami wave heights," co-author Eric Dunham, a Stanford geophysicist, said in a statement. "Sound waves propagate through water 10 times faster than the tsunami waves, so we can have knowledge of what's happening a hundred miles offshore within minutes of an earthquake occurring. We could know whether a tsunami is coming, how large it will be and when it will arrive."

The Japan Meteorological Agency issued a tsunami warning three minutes after the 2011 earthquake struck, but the agency underestimated the height of the waves. A revised warning of the bigger tsunami was sent out within minutes, but some residents did not hear or heed the new alert. In March, the country unveiled a new tsunami warning system with upgraded seismic sensors and offshore buoys to better track incoming waves. [Infographic: How Japan's 2011 Earthquake Happened]

The researchers said the varying orientation of faults offshore of tsunami-prone regions, such as Alaska, Chile and the Pacific Northwest, means the model's telltale acoustic signal could vary from region to region.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The ideal situation would be to analyze lots of measurements from major events and eventually be able to say, 'This is the signal,'" lead author Jeremy Kozdon, a mathematician at the Naval Postgraduate School, said in the statement.

The U.S. tsunami warning system detects and locates potential tsunami-triggering earthquakes with seismic monitors and ocean-bottom pressure sensors, and uses computer models to predict the impact of incoming waves. Countries such as Chile are also exploring GPS-based tsunami alert systems, which provide more accurate estimates of ground movement than do seismic monitors (seismometers).

Tsunamis occur when earthquakes or undersea landslides suddenly displace the ocean floor and the sea above it, triggering a wave.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.