X-Rays Reveal Lost Aria in 200-Year-Old Opera

Scientists have helped to restore Luigi Cherubini's opera "Médée" to its original glory.

A lost aria, or solo song, from the piece, which Cherubini apparently smudged out in spite more than 200 years ago, has been revealed by x-ray scans.

Cherubini was an Italian composer who worked mostly in France and counted Ludwig van Beethoven among his contemporaries and admirers. When Cherubini's French-language opera "Médée" premiered in 1797, critics whined that the opera was too long, and as legend has it, the composer cut the piece by about 500 bars.

Médée revival

A shortened Italian translation of the opera became the dominant form of that opera into the 20th century. But today, many opera-goers and critics long to see "Médée" — which tells the wrenching Greek myth of Medea — as Cherubini first wrote it.

A well-received bicentennial version of the opera in its original form was produced in New York by Opera Quotannis in 1997; critic Peter G. Davis declared at the time that the doctored form "we've been hearing all these years, should now be permanently set aside." Back in December, an audience displeased with a radical take on Cherubini's "Médée" apparently lobbed obscenities at the performers in Paris and shouted "Stop the desecration of opera," according to the New York Times.

Now scientists are taking part in the revival, too. In an original manuscript of Cherubini's "Médée," the closing lines of the aria "Du trouble affreux qui me dévore" ("The terrible disorder that consumes me") are blacked out. Scholars sent the copy to physicists at Stanford University's Linear Accelerator Center (SLAC) in Menlo Park, Calif., where the lost musical notes were recovered with the help of powerful X-rays. [Image Gallery: How Technology Reveals Hidden Art Treasures]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It was amazing to be able to see the complete aria," SLAC physicist Uwe Bergmann said in a statement. "For me, uncovering the composition of a genius' work that had been lost for centuries is as thrilling as trying to uncover one of the big secrets of nature."

Smudges made invisible

In Cherubini's time, ink often came with a high metal content. Scientists at SLAC determined that the composer's manuscript had preprinted lines made in high-zinc ink, while Cherubini's handwritten notes were scribbled with ink high in iron. The black charcoal smudges covering the aria, meanwhile, contained mostly carbon.

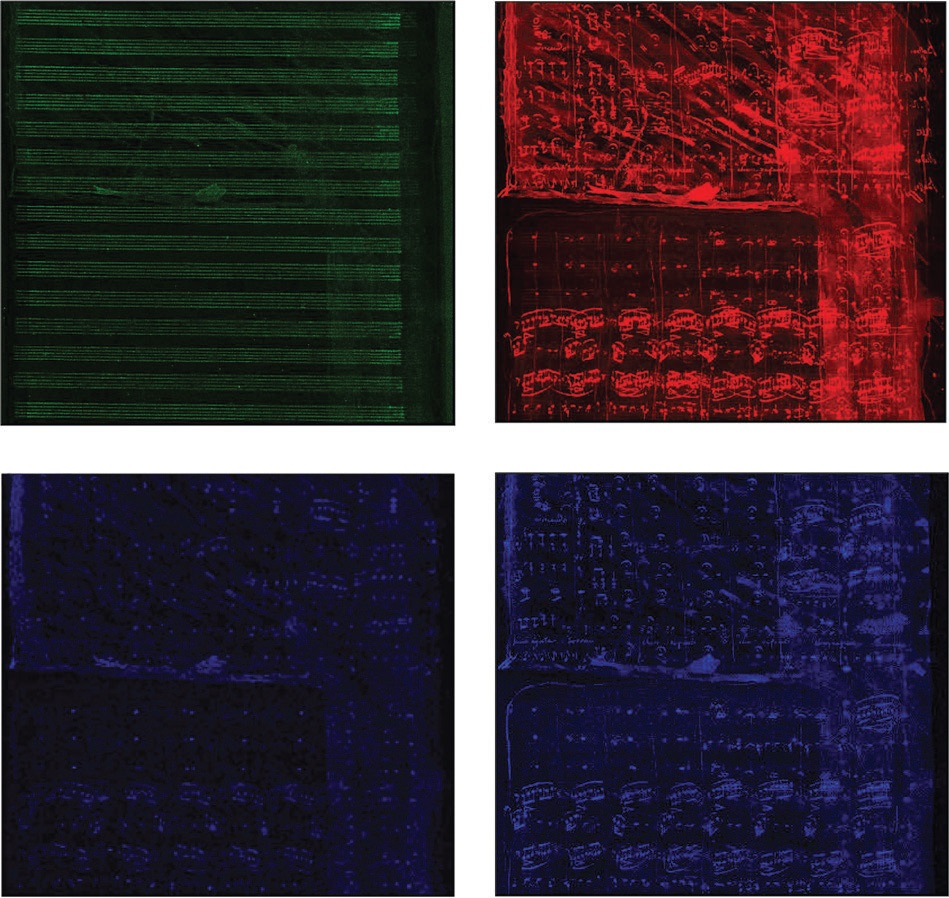

Scientists took advantage of those chemical differences in their analysis of the manuscript. The synchrotron lightsource at SLAC accelerates electrons so fast that they produce a bit of high-energy X-ray light, which can be collected and focused into powerful beams for experiments. Researchers at the lab used X-ray energies associated with zinc and iron to make tiny amounts of these metals fluoresce, allowing them to effectively look through the manuscript's carbon smudges and see the ink underneath.

It took about eight hours to scan each side of the page line-by-line with a beam smaller than the width of a human hair.

"It's similar to a dot matrix printer," Samuel Webb, a beam line scientist at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) at SLAC, who ran the experiment, said in a statement. "Whenever we saw iron we would put a little digital red ink blot down, and whenever we saw zinc we'd put a little green dot down."

The scientists did hit one snag in digging up Cherubini's lost composition; the X-rays made the paper invisible, too, meaning both sides of the manuscript were visible in one confusing jumble of notes.

But Cherubini's handwritten musical notes consistently have heads attached to the right side of their stems, the researchers said. By looking at which musical-note heads leaned to the left and leaned to the right, the team reconstructed the two separate pages.

A recording of it the lost aria be heard here.

SLAC scientists previously recovered writings of the ancient Greek mathematician Archimedes covered up by a Christian monk's notes. Art conservationists, too, have been turning noninvasive scanning technologies like X-ray scanners to peek at the underpaintings hidden in masterpieces. Scientists at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, for example, are currently looking for a secret artwork buried underneath 380-year-old Rembrandt painting.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.