Lung Transplants Controversial for Cystic Fibrosis Patients

Ten-year-old Sarah Murnaghan, who has cystic fibrosis, is awaiting a lung transplant that could save her life, but the procedure is not a cure for her condition, and comes with significant risks, research shows.

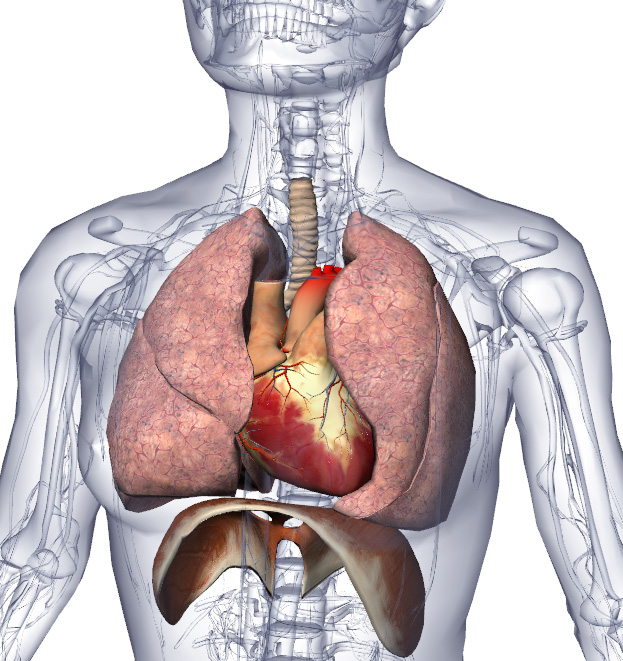

Cystic fibrosis is a genetic condition in which the body produces abnormally thick mucus, which builds up in the lungs, pancreas and digestive tract. As a result, the condition causes breathing and digestive problems, and puts patients at risk for infections. The average life expectancy for cystic fibrosis patients is in the mid-30s, according to the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF).

Patients with cystic fibrosis need lung transplants when the damage to the lungs is so severe that doctors can do nothing more to treat them, said Dr. Maria Franco, a pediatric pulmonologist and director of the cystic fibrosis center at Miami Children's Hospital.

However, lung transplants in cystic fibrosis patients are controversial because some studies suggest the procedure does not prolong life or help patients live better on a day-to-day basis, according to the Mayo Clinic.

Because the donor lungs transplanted into the patient do not have the cystic fibrosis gene, the cells that line the lungs do not produce thick mucus. However, the patient still has cystic fibrosis, because the defective cystic fibrosis gene is in all of the rest of the cells in his or her body. That means cells in the sinuses, pancreas, intestines, sweat glands and reproductive tract will still produce thick mucus, according to the CFF.

What's more, cystic fibrosis patients who undergo a lung transplant need to take immunosuppressive drugs that put them at even greater risk of infections, the CFF says. (Bacteria already in the body from previous infections may infect the new lungs.) Patients are also at risk of organ rejection.

In a 2007 study, researchers at the University of Utah examined the risks and benefits of lung transplants for cystic fibrosis patients. They looked at 514 children with cystic fibrosis on the waiting list for a transplant, including 248 who did receive a transplant. Less than 1 percent of the transplant patients benefited from the procedure, the researchers concluded.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

About half of the patients in each group died; there was no evidence that those who received transplants lived longer, the researchers said. The average survival time was 3.4 years after the transplant, and about 40 percent lived for at least five years after the transplant.

The study was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

About 150 to 200 people with cystic fibrosis have received a lung transplant each year since 2007. About 80 percent of the cystic fibrosis patients who receive a transplant are alive one year after the transplantation, and more than 50 percent are alive after five years, the CFF says.

Some patients do much better after a lung transplant because the lung damage is the driving factor behind the illness,Franco said. "Once you fix that part, everything else is much easier to take care of," she said.

Franco said that of the three patients she has treated who have undergone lung transplants, two are doing very well. Both were teenagers when they underwent the transplant, and one has since finished college. But the third patient caught an infection and died, she said.

The first year after a transplant is the most critical, and doctors are on the lookout for complications they know can arise, Franco said.

Because it is not common for cystic fibrosis patients to have severe lung damage as young children, those who undergo the procedure are typically teenagers, Franco said.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.