It's time for the Arab Muslim world to reclaim its lost tradition of astronomical learning, one prominent researcher says.

Building a new generation of observatories would spark interest in fundamental research across the region, which in recent years has taken a much more utilitarian approach to science, said Nidhal Guessoum, a professor of physics and astronomy at the American University of Sharjah in the United Arab Emirates.

"Astronomy has a natural place high in the landscape of Arab Islamic culture," Guessoum wrote in a commentary published in the June 13 issue of the journal Nature. "It must be brought back." [History & Structure of the Universe (Infographic)]

A lost tradition

Astronomy has traditionally been important in the practice of Islam, Guessoum wrote, helping believers calculate prayer times and locations, determine the direction to the holy city of Mecca and map out the dates of festivals and pilgrimages.

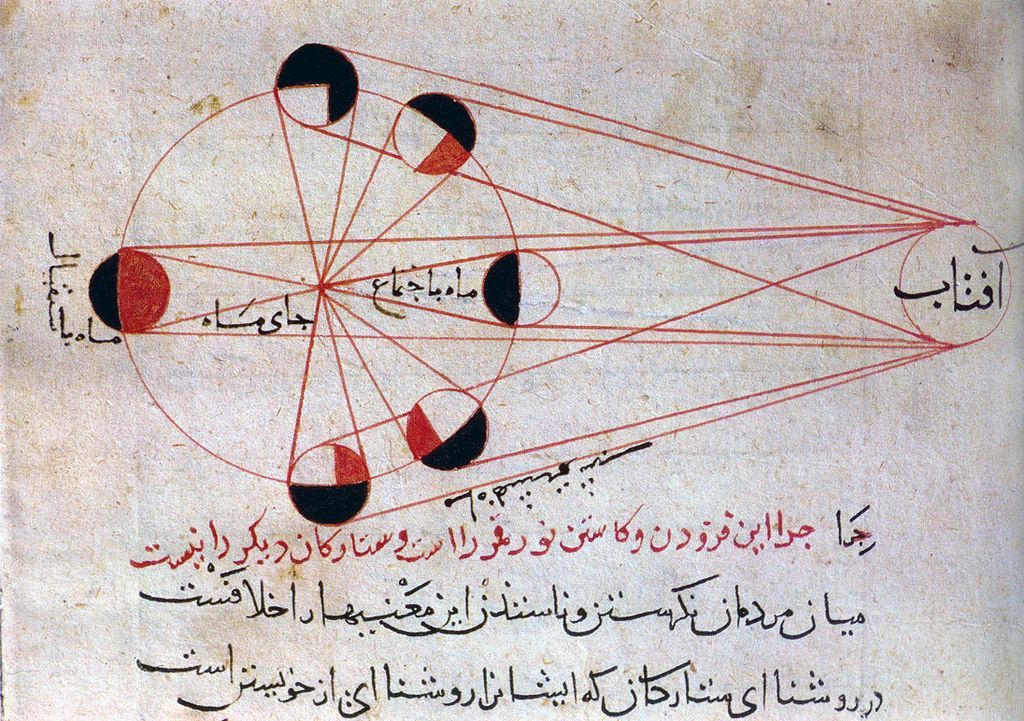

As a result, astronomy flourished in the Muslim world from the ninth through 16th centuries A.D., with great observatories being built in what is now Iraq, Syria, Turkey, Iran and Uzbekistan.

"Thus hundreds of stars and constellations have Arabic names, such as Altair, Deneb, Vega and Rigel," Guessoum wrote. "Today, more than 20 lunar craters bear the names of Muslim astronomers, including Alfraganus (al-Farghani), Albategnius (al-Battani) and Azophi (al-Sufi)."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This golden age came to an end in the late 1500s after conservative clerics and rulers gained sway, placing ever more value on religious knowledge over scientific pursuits.

European colonization of the region in the 19th century sparked a brief resurgence, with new observatories going up in places such as Algeria, Lebanon and Egypt, Guessoum said.

But the interest mostly went home with the colonizers. When Arab nations gained their independence, Guessoum wrote, they tended to prioritize applied sciences such as petrochemical engineering and pharmaceuticals.

Today, there are just two operational medium-size telescopes in the entire Arab world, he noted — one in Algeria and one in Egypt.

Guessoum quantified the current state of Arab astronomy research by analyzing peer-reviewed papers published in the field from 2000 through 2009. He found that, of every 1,000 science papers with a first author from an Arab nation, only three were in astronomy.

By contrast, the proportion ranges from 10 to 25 per 1,000 papers for the United States, China, India, Japan, Brazil and Spain.

"The entire Arab world published fewer astronomy papers than Turkey alone, and substantially fewer than South Africa or Israel," Guessoum wrote. "Citation figures are worse: Arab astronomy papers were cited less often than Turkey's, South Africa's or Israel's."

What to do about it

The Arab world doesn't have to stay at the back of the astronomical pack forever, Guessoum said.

The region has a number of good observatory sites, high-altitude places with clear, dry air. And funding large telescopes is eminently achievable, as a number of Arab countries — such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates — have considerable oil wealth at their disposal.

Guessoum advocates building several professional-quality observatories, as well as setting up astronomy and astrophysics degree programs at all public universities in the Arab world (such programs currently "can be counted on two hands," he wrote). He also recommends that funding be provided for Arab students to pursue doctorates abroad.

Promoting an Arab astronomy renaissance will require the combined efforts of national governments, universities and advocacy organizations across the region, Guessoum said. He hopes his comment piece in Nature helps get the ball rolling.

"It will take at least a decade, and so [we] need to start ASAP," Guessoum told SPACE.com via email.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.