Infections Linked to Mood Disorders

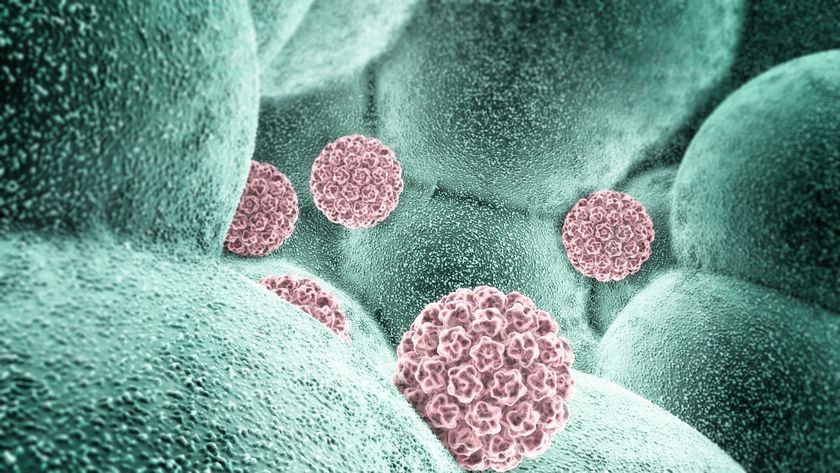

Infections and autoimmune disorders may increase the risk of developing a mood disorder such as depression later in life, a new study from Denmark suggests.

In the study, which included more than 3 million people, those who were hospitalized for infections were 62 percent more likely to subsequently develop a mood disorder compared with people not hospitalized for infections. And those hospitalized for an autoimmune disease were 45 percent more likely to subsequently develop a mood disorder. Autoimmune diseases are those in which the immune system goes awry and attacks the body's own cells or tissues.

The risk of mood disorders increased with the number of times a person was hospitalized. Those who were hospitalized three times with infections during the study had double the risk of a mood disorder, and those who were hospitalized seven times had triple the risk, compared to those not hospitalized with infections.

The findings support the hypothesis that inflammation, from either an infection or autoimmune disease, may affect the brain in a way that raises the risk of mood disorders, the researchers say.

If the link is confirmed in further studies, the researchers said, their estimates show that infections could be responsible for up to 12 percent of mood disorders.

However, the study found an association, and cannot prove that infections or autoimmune diseases are the cause of mood disorders. It's possible that other factors, such as stress or the experience of hospitalization, may explain the link, said Ian Gotlib, a professor of psychology at Stanford University, who was not involved in the study.

The study is published today (June 12) in the journal JAMA Psychiatry.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Infections and mood disorders

The study included people born in Denmark between 1945 and 1996 who were followed until the end of 2010.

During the study, more than 91,000 people visited a hospital for a mood disorder, including bipolar disorder or depression. Of these, about 32 percent visited hospitals for an infection before their mood disorder, and 5 percent visited the hospital for an autoimmune disease before their mood disorder.

The risk of a mood disorder was greatest in the first year following an infection or autoimmune disease.

People who visited a hospital for both an infection and an autoimmune disease had a greater risk of developing a mood disorder than those who visited a hospital for either of the two conditions alone. This may indicate the two conditions interact to increase the risk of mood disorder, the researchers said.

Because the study looked at information from only people hospitalized with infections, autoimmune disorders and mood disorders, it’s not clear whether the findings may apply to people with less severe infections, or mood disorders.

What's the cause?

Gotlib called the study "impressive" and said it raises important questions. Previous studies have shown that people with depression have lower numbers of T cells (a type of immune cell), and are at increased risk for autoimmune diseases, Gotlib said.

But there are also many other risk factors for mood disorders that were not taken into account in this study, such as smoking and socioeconomic status, Gotlib said. Future studies should attempt to untangle whether infections are really the cause of mood disorders, or if the two just happen to occur together.

In addition, studies should investigate how, on a biological level, infections and autoimmune diseases might affect the brain to cause mood disorders, Gotlib said.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

2nd measles death reported in US outbreak was in New Mexico adult

CDC data reveal plummeting rate of cervical precancers in young US women — down by 80%