Supreme Court Ruling Could Drop Price of Breast Cancer Gene Test

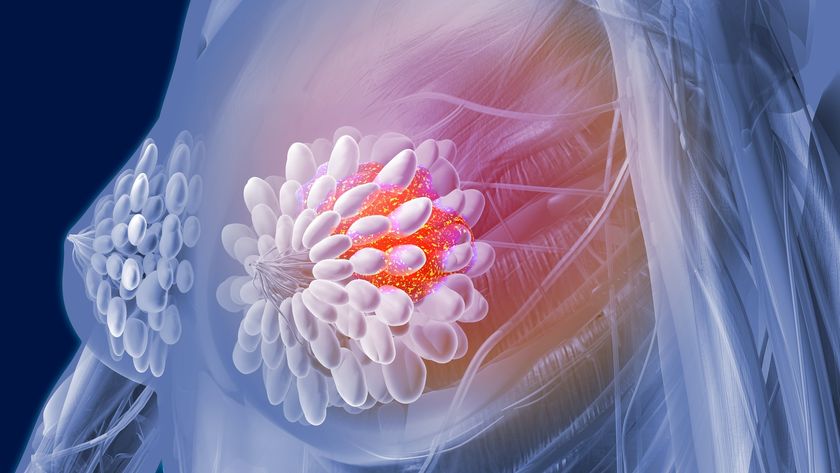

The price of testing for the breast cancer genes BRCA1 and BRCA2 could come down in the near future as a result of a Supreme Court ruling on gene patents today (June 13), some experts say.

In a 9-0 ruling, the Supreme Court determined that human genes are not patentable, and that the company Myriad Genetics Inc. cannot hold patents on two genes, BRCA1 and BRCA2, which are linked with an increased risk of breast and ovarian cancer.

Currently, women who want genetic testing for mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 have to use the Myriad test, which costs more than $3,000 and is not always covered by insurance. But now that Myriad's patents are no longer valid, other companies will be able to develop tests for BRCA1 and BRCA2. The additional competition could bring the price of testing down, experts say.

Some companies have already developed genetic tests for other breast cancer genes, and could easily add BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes to their tests, said Robert Cook-Deegan, a professor of genome ethics, law and policy at Duke University's Institute for Genome Sciences and Policy.

"It's fairly safe to predict that in coming months you will see BRCA testing picked up in at least a few places," Cook-Deegan said. Although Myriad is allowed to keep its patents for synthetically created DNA, this does not matter for diagnostics, he said.

Dr. Harry Ostrer, a professor of pathology and of genetics at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, is also developing a genetic test to determine breast cancer risk. The test includes more than 20 genes that put women at risk for breast cancer, and now Ostrer has the go-ahead to add BRCA1 and BRCA2.

Eventually, Ostrer said the price of breast cancer genetic testing could drop to between $500 and $1,000.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But the price drop will not be immediate, since it takes time to validate a test and get it approved for a specific purpose, said Dr. John Conley, a law professor at the University of North Carolina who specializes in technology issues.

"I don't see the market changing dramatically, immediately," Conley said. "There would be a lot of work to do from going from the state of permission to being able to do it," Conley said.

Ostrer said he sees the price of genetic testing for breast cancer coming down within the year. But he admitted that his own test is still months away from being ready.

Other experts said they were not so certain that the price would drop at all. That's because the cost of medical care tends not to be as influenced by competition as other goods and services.

"Medical markets are not like the markets for PCs or cellphones, but are stickier and more complicated and price competition is not always intense," Cook-Deegan said. "There will likely be competition, but that may not take the form of dramatically lower prices."

Another challenge for competitors will be interpreting test results once they have a test. Over the nearly two decades that Myriad has been conducting tests on BRCA1 and BRCA2, the company has amassed a large amount of information that tells doctors what the test results mean. And it keeps the database to itself.

"With or without patents, it's an advantage to them," Conley said of the database.

Ostrer said that there is already much known about the genetics of breast cancer risk, and that some researchers are trying to replicate Myriad's database. But he also called for Myriad to open its database to help other researchers interpret results.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.