Past Mega-Quakes Left Mark on Canadian Coast

Thanks to decades of geologic detective work, scientists know that on Jan. 26, 1700, at 9 p.m., a massive earthquake and tsunami hit the Pacific Northwest.

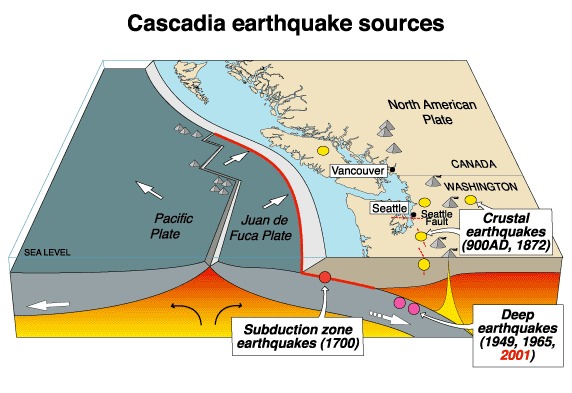

Born from the Cascadia Subduction Zone, the earthquake may have cleaved the 620-mile-long (1,000 kilometers) offshore fault from Northern California to Canada. Researchers don't yet know; they must play connect the dots with clues left behind in billowy layers of sand and mud.

A group of Canadian geologists is connecting some of these dots, with the first record of past earthquakes from the Pacific Coast of Vancouver Island. The team discovered evidence of 21 temblors in the past 11,000 years, including the 1700 quake and a 1946 shaker centered on the island. The new findings are detailed in the June 12 issue of the Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences.

Earthquake archive

The history of Canadian earthquakes adds to an archive being assembled of the Cascadia Subduction Zone, which marks the collision between the North American and Juan de Fuca tectonic plates. Subduction zones, where one plate slides beneath another, trigger the biggest earthquakes and tsunamis on the planet, such as the 2004 Sumatra and 2011 Japan disasters. The 1700 megathrust quake likely rivaled those two catastrophic quakes in size, researchers think. [The 10 Biggest Earthquakes in History]

The Vancouver Island records match up with16 past earthquakes discovered in disturbed seafloor sediments offshore of southern Vancouver Island, Washington and Oregon, the researchers said. But not all of the ancient quakes seen along the southern part of the subduction zone had a counterpart in the new record.

"Perhaps not every megathrust earthquake is equal to another," said Audrey Dallimore, study co-author and a marine geologist at Royal Roads University in Victoria, B.C. "Some may only rupture the southern part of the zone."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

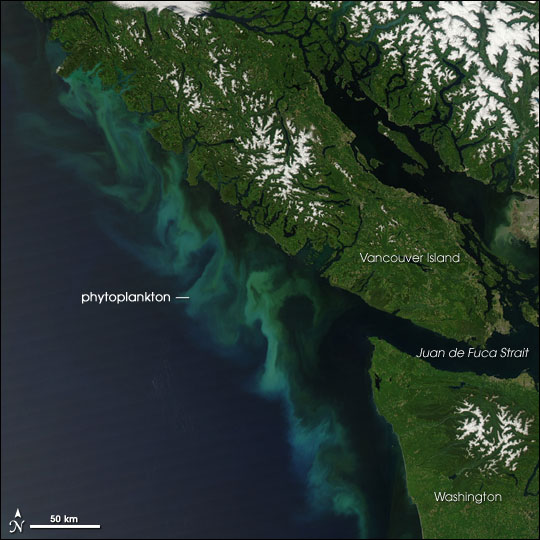

The new earthquake record is from Effingham Inlet, a former glacial fjord in Barclay Sound, on the southwestern coast of Vancouver Island. A crew shoehorned an ocean drilling ship into the narrow inlet and drilled down to bedrock, pulling up 138 feet (42 meters) of sediment in what is called a core. Because there's little oxygen in the inlet's bottom waters, no marine creatures mix up the sediments, leaving a nearly pristine archive of the past.

"The sediments are laid down year by year like tree rings," Dallimore said. "These millimeter-thick layers go back thousands and thousands of years."

Two clusters of quakes

The disturbed layers left by earthquakes aren't evenly distributed through time, but rather repeat about every 200 years and every 900 years (called recurrence intervals). Carbon dating of organic material, along with ash from Mount Mazama's eruption in 5,677 B.C., precisely dates the layers. (Mount Mazama is part of the Cascade Volcanic arc in Oregon.)

The bimodal pattern (of 200 and 900 years) could reflect the island's two earthquake sources — the offshore subduction zone and local faults, such as the one that caused the 1946 earthquake, Dallimore said. But evidence elsewhere on the Cascadia Subduction Zone also suggests the giant fault rips apart at irregular intervals.

"We know the longest time between earthquakes [in Effingham Inlet] is 1,000 years. The next earthquake could be tomorrow or it could be 700 years from now," Dallimore said.

Filling in gaps

To complete the picture, Dallimore and her colleagues have collected more samples from inlets further north on Vancouver Island. The researchers plan to compare those cores to Effingham Inlet and American sites to better understand how the Cascadia Subduction Zone ruptures along the coast.

Chris Goldfinger, a geologist at Oregon State University who was not involved in the research, said the study "was a very nice piece of work."

"It's becoming more and more clear that big [Cascadia] subduction earthquakes are reliably recorded in many environments, something that will eventually allow us to combine all these data and estimate slip models and magnitudes for past earthquakes," Goldfinger said.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.