Detecting Social Patterns from Shifting Dialects

This Behind the Scenes article was provided to LiveScience in partnership with the National Science Foundation.

Knowing glances may dot a room when listeners hear the line, "You say tomato, I say tomahto," from the popular Gershwin song "Let's Call the Whole Thing Off." Whether you're from Philadelphia or Fresno, Winnetka or Waco, your dialect often identifies you with a particular locale.

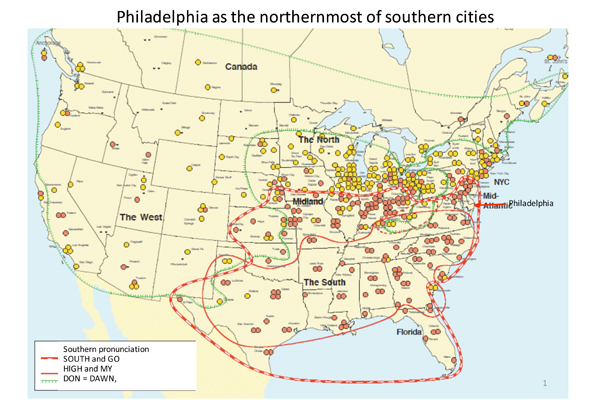

Now using a powerful computer program, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania provide insights into a significant change in the dialect of Philadelphians. In a century's time, the sound of Philadelphia has shifted from a somewhat southern accent to a more northern one. And it's not just a few areas of Philadelphia. The entire city shifted. "The reversal indicates major changes in social patterns," says University of Pennsylvania linguist William Labov.

Considered the northernmost of the southern cities, Philadelphia has continued to progress toward a more northern sounding dialect. "All those things that align Philadelphia with the south are disappearing," says Labov. "The South is receding, and language is very sensitive to profound social attitudes." Younger people are less likely to pick up or use southern inflections.

"When we study how language changes, we gain an understanding of what we're like as human beings," says Labov. "

Regional dialects in America are getting more and more different and carrying each region away from the other."

One Vowel at a Time

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Labov and his colleagues developed their conclusions using a program called Forced Alignment & Vowel Extraction (FAVE). It allowed them to automatically analyze vowel sounds on recordings of interviews with speakers from 89 neighborhoods throughout the city whose birth years ranged from 1888 through 1991. The interviews were compiled yearly beginning in 1973 as part of a long-term language study undertaken by Labov and his students.

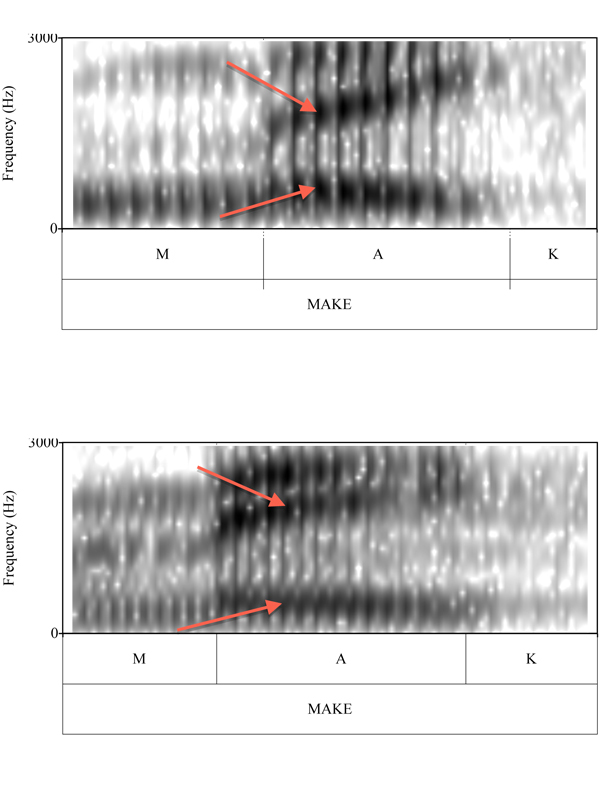

"We wanted to make automatic what, in the past, was a painfully slow hand process," says Labov of the computer analysis program. Previously, vowel analysis required listening to a digital recording on a computer and physically stopping the audio to make a measurement of a vowel sound. The few automated analysis programs available required quality checks to determine if the program had correctly identified the start and end of a vowel sound.

"When the original algorithm was working correctly, very few errors were found. However, when it was off, it was off by a lot and introduced numerous errors," says Josef Fruehwald, a doctoral student working with Labov. Older analysis programs were also unable to accurately sort through the extraneous noises introduced on the recordings by household sounds such as water running or a television playing in the background.

Two years in the making, the FAVE program follows every word on an interview transcript and looks up the each word's sounds in a pronunciation dictionary. For the word "bat," for instance, the algorithm marks the beginning and end of b, a, and t. It then provides analysis for vowels throughout the entire interview. The program is so efficient that in one hour it provides 7000 measurements for one interview. Before FAVE, an analysis could take 3 days and yield just 300 measurements.

"The program has really exploded the volume of data we get from each speaker," says Fruehwald. The researchers have measured about one million vowels in the study. The increased data improves the accuracy of language analysis and provides a higher level of confidence in the results.

Moving Data

Presenting such a large amount of data in a meaningful way was paramount for Fruehwald. So he created motion diagrams of how vowel sounds in the study changed over time. One data point on the diagram for the "aw" sound, for instance, moves up into a more southern pronunciation for about 75 years and then turns back toward a more northern pronunciation.

Fruehwald says that the software is finding a larger audience as evidenced by an increasing number of related presentations at professional conferences. "This is all going to be taking off," says Fruehwald. Linguists interested in using the FAVE suite can download it or use its online interface free of charge at the FAVE site.

The End Result

Sound changes such as those studied here remain a major obstacle to communication, especially when it comes to machine recognition of spontaneous speech. Companies engaged in creating speech recognition programs have used the Atlas of North American English, produced by Labov's research group, to define the range of dialects that must be represented in the data base of sounds used to "train" the speech recognition software. Philadelphia teachers are also using the group's results to refine their classroom plans so that they account for speech variations among students.

Future research by the Labov team will involve learning why accents in all of the study neighborhoods moved in the same direction at the same time and how minority participation impacts changing dialect patterns.

Editor's Note: The researchers depicted in Behind the Scenes articles have been supported by the National Science Foundation, the federal agency charged with funding basic research and education across all fields of science and engineering. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. See the Behind the Scenes Archive.