Don't Hurt That Robot! How Morality Muddles Perception of a Mind

Although people can't directly experience the consciousness of another, they take for granted that other people have minds — that others can think, remember, experience pleasure and feel pain.

People, however, don't typically attribute such minds to robots, corpses and other beings with no apparent consciousness, except if these beings are put in harm's way, new research suggests.

Sympathy for victims

In a series of experiments by Harvard University researchers, people were more likely to ascribe the characteristics of an active mind to non-conscious beings when they were intentionally victimized than when they were unharmed. Examples included a permanently vegetative patient who was starved by a corrupt nurse, a robot that was stabbed by its caretaker, and a corpse that was violated by a mortician.

"People seem to believe that having a mind allows an entity to be part of a moral interaction — to do good and bad things, or to have good and bad things done to them," study researcher Adrian Ward, a psychological scientist at Harvard, said in a statement. "This research suggests that the relationship may actually work the other way around: Minds don't create morality, morality creates minds." [Top 10 Mysteries of the Mind]

In the first experiment, participants read a vignette about "Ann," a permanently vegetative patient who was unresponsive to stimuli, completely dependent on hospital staff to survive, unable to feel pain and not expected to recover. One group of participants read a version of the story in which Ann was properly taken care of by her nurse. In the darker version of the story, the nurse intentionally unplugged Ann's food supply each night, hoping her patient would eventually starve so that the nurse could collect cash promised to her by a distant relative named in Ann's will.

Both groups of participants were asked to gauge the level of Ann's awareness, capacity for agency and ability to feel pain — all adding up to a general measure of mind attribution. Those who read that Ann was starved tended to attribute more mind to her than those who read that she was unharmed, the researchers found.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

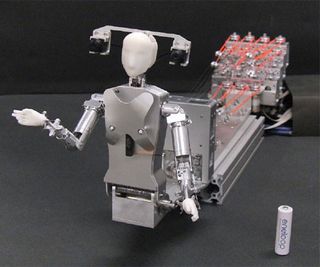

The same pattern was true for participants who read two different versions of a story about "George," a highly complex social robot. Those who read that George was routinely jabbed in his sensors with a scalpel thought the robot had more consciousness than those who read a version in which George was not a target for harm by his human caretaker.

Humanization vs. dehumanization

The findings could help explain why there is fierce disagreement on issues like abortion, assisted suicide and animal rights; a person's moral standing could greatly influence how they view the capacity for thinking, feeling pain and consciousness in a fetus, a comatose patient, or a lab rat, the study suggests.

"When these entities are thought of in moral terms, they're attributed more mind," Ward said in a statement. "It seems that people have the sense that something wrong is happening, so someone must be there to receive that wrong."

Meanwhile, when a fully conscious adult human becomes the victim of wrongdoing, he or she is attributed less mind, Ward and colleagues found, which is consistent with previous research on victim dehumanization. A set of participants who read a story about "Sharon," a woman physically abused by her boss, saw her as less able to experience pain and less aware than those who read a story about Sharon and her boss that involved no abuse.

While beings that have a mind to begin with are dehumanized through victimization, entities with absent or limited consciousness gain minds by being harmed, the researchers say. The researchers added a worthwhile avenue of study may be to investigate the threshold between these two opposing effects, where people stop humanizing victims and begin to dehumanize them.

Their findings were detailed this month in the journal Psychological Science.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Most Popular