No, You Can't Outrun a Tsunami

Maybe the fastest man in the world could run a 6-minute mile for 6 miles (10 kilometers) while a terrifying wall of water chased him through a coastal city. But most people couldn't.

Yet a myth persists that a person could outrun a tsunami. That's just not possible, tsunami safety experts told LiveScience, even for Usain Bolt, one of the world's quickest sprinters. Getting to high ground or high elevation is the only way to survive the monster waves.

"I try to explain to people that it doesn't really matter how fast [the wave] is coming in, the point is that you really shouldn't be there in the first place," said Rocky Lopes of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Tsunami Mitigation, Education and Outreach program.

But because they didn't know the warning signals, ignored them or just couldn't get to safety in time, more than 200,000 people died in tsunamis in the past decade. And it's not just tsunamis: Underestimating the power of the ocean kills thousands every year in hurricane storm surges.

Stay off the beach

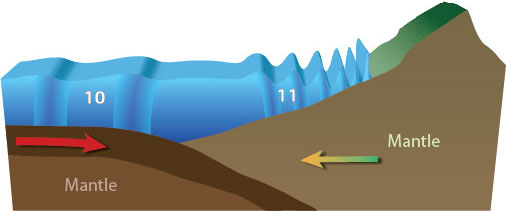

A tsunami is a series of waves caused by a sudden underwater earth movement. The kick-off is akin to dropping a big rock in a children's pool filled with water. In an ocean basin, tsunami waves slosh back and forth, reflecting off coastlines, just like the (much smaller) waves in a child's pool, Lopes said.

Because many people mistakenly think a tsunami is a single wave, some return to the beach after the first wave hits, Lopes said. On March 11, 2011, a man in Klamath River, Calif., died after he was swept away by a second wave while taking pictures of the Japan tsunami, Lopes said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Tsunamis race across the deep ocean at jet speed, some 500 mph (800 km/h). Near shore, the killer waves slow to between 10 to 20 mph (16 to 32 km/h) and gain height. If the offshore slope is gentle and gradual, the tsunami will likely come in looking like a rapidly approaching tide. If the transition from deep ocean to shoreline is steep and cliff-like, then the wave will resemble a movie-like specter, arriving as an onrushing wall of water. [Waves of Destruction: History's Biggest Tsunamis]

Look and listen for warning signs

Either way, standing at the beach, at sea level, means losing perspective. "It's a matter of optical illusion and how fast your eye interprets the speed of moving water," Lopes said. "People just can't estimate the speed of the wave, and [so they] get themselves in trouble."

Linger too long and you may run out of time to find somewhere safe. "If they're on the beach, there's no way in heck they're going to outrun it," said Nathan Wood, a tsunami modeler with the U.S. Geological Survey in Portland, Ore. "Technically, if you're 10 blocks in, and the waves are full of debris [and slowing from friction], there's a chance, but for most people that's not realistic," he said.

So if the beach starts shaking or the ocean looks or sounds strange, head for the highest elevation around immediately.

"Sometimes the only warning you may get are these environmental clues," Lopes said. "These are the indicators that you are in serious danger."

High ground is best in situations like these; steel-reinforced concrete buildings or parking structures work in a pinch, but even climbing trees will help if nothing else is available. Some people who sought refuge in trees survived the 1960 Chile tsunami, though others were torn from their branches.

Why people put themselves at risk

Another fatal mistake people make when fleeing from tsunamis is underestimating how far the water can travel inland, Lopes said. In this graphic video of the 2011 Japan tsunami, shot from a hillside, residents fleeing the tsunami are nearly caught by the powerful wave even after it had already destroyed half the town.

Tsunamis can travel as far as 10 miles (16 km) inland, depending on the shape and slope of the shoreline.

Hurricanes also drive the sea miles inward, putting people at risk. But even hurricane veterans may ignore orders to evacuate. As with tsunamis, a lack of understanding lays at the heart of this willingness to risk everything, according to studies by NOAA.

"We've consulted with social scientists and communications experts, and the number one reason why people stay is that they don't understand storm surge," said Jaime Rhome, storm surge team leader at the National Hurricane Center in Miami.

Hurricane evacuation orders are due to dangers from storm surges, not wind, Rhome explained. "People are enamored with the wind, but it's storm surge that has the greatest potential to take life," he said. "The majority of deaths occurring in hurricanes are from drowning, not wind."

Storm surge is the force of hurricane winds driving the ocean landward, which raises sea level. The water penetrates miles inland. Waves kicked up by the hurricane travel on top of the storm surge, pounding everything in their path. People who go out in the surge — residents who wait too long to evacuate, for example — may find themselves knocked off their feet and swept away.

"People have a hard time imagining seawater can come that far inland," Rhome said. "They can't envision the ocean can rise that high or be that violent."

Editor's note: This story was updated to reflect the March 11, 2011, U.S. tsunami death was at Klamath River, Calif., not Crescent City, Calif.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.